The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Adams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

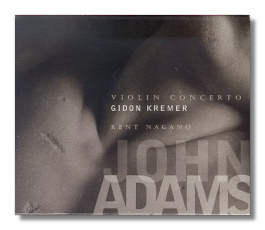

John Adams

- Violin Concerto (1993)

- Shaker Loops (1977/83) *

Gidon Kremer, violin

London Symphony Orchestra/Kent Nagano

* Orchestra of St. Luke's/John Adams

Nonesuch 79360-2

Summary for the Busy Executive: I'm this close to writing in John Adams's name for President.

Why did minimalism get started? Almost every important minimalist, after all, had begun in postwar 12-tone serialism, which at one point overtook neo-classicism as the closest thing to a 20th-century musical lingua franca. While hardly scholarly, I guess two reasons. First, I think it significant that minimalism began with Americans. The sense of dread and doom inherent in most expressive uses of dodecaphony really didn't suit the basic optimism of the American Fifties and Sixties. As Steve Reich once remarked, it's hard to feel Angst "in Ohio, in the back of a Burger King." Second, very few composers want to get to the point where they find themselves retilling the same ground. The actual physical process of putting notes on a staff with pen or pencil or even mouse-click is pretty tedious, compared to what I imagine is the exhilaration of creating in your head. I believe a composer wants a good reason to sit down at the desk. After all, almost nobody makes a living - let alone real money - from writing classical music, which seems as necessary to most people's lives as a solid gold egg timer. You might as well have fun.

It kind of surprises me that minimalism caught on, not only with grant committees and commissioning organizations, but with general listeners, whom I would have thought remote from its rarified philosophic base. However, a recording of Terry Riley's "In C" actually cracked the crossover market, just as Górecki's Symphony #3 did over a decade later. Glass and Reich both make a very nice living from their music, as they tour like minor rock stars. In New Orleans, a poster merely with Glass's picture, plus place and time, packed a hall, and, of course, Glass performed on American TV's Saturday Night Live, one of our commercial icons of hipness. One can speculate as to the reasons for so much success - apart from the music's intrinsic quality - but the success itself shows something important. First, given the opportunity to hook in to new classical music, quite a few people will take it. A Glass or Reich concert brings in a young audience, most of whom, I suspect, listen to non-r&b, "soft" forms of rock.

Given all this success, it surprises me even more that almost every one of the major composers, once - I believe mistakenly - grouped together as "Minimalist," have moved on, and in ways I doubt anyone could have predicted. Glass has begun a rapprochement with Germanic traditions, beginning at least with the cadenza, composed for Firkušný, to a Mozart piano concerto and continuing with a Sibelian violin concerto (more later). Adams seems the most restless of all, flirting with Italian opera buffa in Nixon in China and Mussorgskian epic in The Death of Klinghoffer, moving to a kind of post-Romanticism in recent work. In the meantime, he continues to write the occasional "mainstream" contemporary piece. Reich has always gone his own way fairly methodically, but I fail to see how anyone could call his works "minimal."

It strikes me odd that both Glass and Adams should have produced violin concerti so close to one another, although perhaps not, since the stimulus seems to have come from the enterprising Gidon Kremer in both cases. What remains curious, however, is the ghost of none other than Jean Sibelius lurking in the background, who had been condemned to artistic perdition as far back as the 1940s for Unrepentant Mossbackery. Now composers' views of other composers tend to be somewhat narrow. A composer values other composers usually for what he can appropriate – or steal, if you like. The fading from fashion of a composer often reflects practicing composers' failure to figure out where they can go next along the path of a previous one, and this really depends on a prevailing view of that composer's work.

The view of Sibelius has undergone many changes. When he began, he seemed to bring a revolutionary agenda to the table of symphonic classicism. By the time of his latest works, most regarded him as a classic himself. Indeed, in a poll conducted by an American cultural journal of the 1930s, Sibelius beat out Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, and Brahms as Greatest Symphonist. Mahler, Nielsen, and Bruckner probably didn't even show up. Outside of England, to a great extent artistically insulated from America and the European continent, Sibelius had very few progeny. Scandinavian and Finnish composers acted out Oedipal artistic dramas on the anxiety of influence, just as Irish writers did in the wake of Joyce and Yeats. By the 1940s, the musically hip regarded Sibelius as relevant to the music scene as Pachelbel, and the priests of the New Jerusalem of the Fifties and Sixties - as opposed to people who "just listen" - seemed to look on Sibelius as a virus to be stamped out. It was kind of like watching names of excommunicants being chiseled off public buildings. Believe me, almost nobody was seriously talking about Sibelius at this time. In most books about modern music, even today, Sibelius is lucky to get a mention, while Mahler rates chapters (not that he doesn't deserve them).

Fortunately, things come around. I should have felt a signal change in the wind when I heard a Michael Steinberg talk about the composer which emphasized the music's revolutionary daring. I admit that at the time I felt nothing other than an "isn't that strange." By now Sibelius has become respectable again, with renewed recording interest (and not just in the symphonies and concerto) and at least two of America's most successful composers creatively rediscovering him.

What exactly have they rediscovered? For one, they've rediscovered Sibelius's orchestral colors, the way he makes the violin sing, as well as his emotional landscape. The Glass concerto essentially abstracts the Sibelius: I think of it as the Sibelius concerto without real themes. I'm not all that big on it myself, but I do find it interesting that Glass chose this particular model. Adams, I believe, has done more, working changes on Sibelius's formal methods. If you read traditional analyses of Sibelius's symphonies, you find they have a great deal of trouble agreeing about where the major structural points, in the context of sonata-allegro procedures, occur. Steinberg, I believe, has hit the mark exactly with his comment that Sibelius doesn't give you traditional development. Instead, the composer seems to have all the pieces of the symphony spread out on the table before him, like the shapes of colored glass for a kaleidoscope. Sibelius plays with the possibilities of combination and juxtaposition of these pieces, rather than of development and Beethovenian "becoming," where the implications of themes reach full realization over the span of movements.

Adams goes for Sibelian juxtaposition: it's just that he uses fewer pieces. The new pieces consist of "fractals" and mutations of the old. As far as I can tell, for example, the first movement consists of two ideas, virtuosically varied - by pitch, by rhythm, by orchestral color. The first, a repeating pattern, appears in the orchestra at the very opening, while the second makes up the musical matter of the solo violin. To a great extent, they remain independent and apart, with the forces that introduced them. The repetition links the work to Adams's minimalist days, but his use of it here merely emphasizes how far he's come. As you know, an ostinato (Italian for "obstinate") is a clearly-defined phrase that repeats at the same pitch, usually in immediate succession, and persists throughout a composition. What Adams gives to the orchestra, strictly speaking, is no ostinato. He does give the orchestra a clearly-defined phrase that persists throughout the first movement, but he continually varies it while managing to retain the idea's basic shape. Basic rhythm switches between three, four, and perhaps points east; phrasing and even the rate of the pulse changes in brilliantly odd ways (some of Elliott Carter's "metric modulation" might be happening here) - all this in addition to the usual sequential and ear-stretching orchestral variation. The violin part plays the same game with its own idea and amazingly does so in essentially a solo line. Adams "colors" the violin idea by throwing in just about every expressive string technique - standard as well as the ones he invents. It's a bit like watching two Claymation shapes transmogrify. For the listener, the key to the movement is to commit to memory the opening measures of the orchestra and of the violin.

Adams titles the slow movement "Body through which the dream flows," after a poem by American Robert Haas. Adams has not only achieved a rapt beauty here, he's discovered it. I know of no other sounds like these. The formal structure relates to chaconne (a repeating bass line or harmonies underneath an ever-changing "top"). However, as in the first movement, the repetition lacks strict application. The ground idea becomes really a set of prominent intervals, notably a rising and falling fifth. It's mainly something for the ear to fix on, in rhythmically and melodically loose passages. The violin sings, and ravishingly, but I doubt anyone would call the song a beautiful tune. It's certainly nothing you'd go away humming, at least the first few times around. For me, the power of the movement lies neither in the bass line nor in the violin, but in what I'd call, generally, the texture. Violin and bass lines move more or less together. At the same time, there are tiny orchestral sighs, almost out of or beyond time, like the quiet breathing of a sleeper. The movement ends in quiet beeps, little sonic beacons firing from the brain's neurons. I can tell you what's going on, but I can't account for its profound power, at least not in the ways I've known music to move me . This music sings of the body and the "physics" of the dream. Adams sets your heartbeat to the music's pulse.

The emotional weight of the concerto, as in the Sibelius concerto, lies in the first two movements. The third movement, a glittering toccata, raises Cain and blows off steam, mainly playing games with ascending and descending runs of the scale, with some tasty chordal progressions thrown in for free. Again, Adams uses two main ideas, but here he allows violin and orchestra to share them in the competition we associate with the traditional concerto. I don't understand how people keep their seats in the concert hall while this plays. It reaches the energy level of the fast parts of the Bartók Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta. Folks, this concerto is a 20th-century masterpiece, no kidding.

Kremer plays the concerto like he can't wait to get to the next phrase. "Committed" just begins to describe his playing. His tone - which in the past I've found nervous and a bit steely – warms up considerably for Adams. As good as Kremer is, Nagano and the orchestra take your breath away. Above all, this is music of several simultaneous "layers," and balance or clarity is essential to the work's effect. Nagano not only clarifies, he makes the layering beautiful. In the first movement, I tried to guess how he brought it off. By the second movement, my critical faculty shut down, and I completely gave over to wide-eyed wonder at the poetry he achieved. He has definitely found the music behind the notes. An incredible performance all 'round.

Shaker Loops, the first of his compositions Adams acknowledges as Minimalist, was, not coincidentally, the first piece of his I heard. I bought the LP (solo septet version) sometime in the late 1970s under the impression I'd be hearing an heir to Appalachian Spring. My mistake and another early encounter with Minimalism (the first encounters were Reich's "It's Gonna Rain" and "Come Out"). Reich and Adams both based themselves in San Francisco at the time, so an influence of Reich on Adams - seen in the term "loops" - is likely. I admit I found Reich interesting, though I didn't consider what he did music: a strong air of laboratory control seemed to hang about his work. In those days, new music meant mainly post-Webernian serialism, especially as practiced by Babbitt, Nono, and Boulez. I was used to music that changed rapidly and complicatedly, "melody" lines that jumped about like a slide whistle or booped and squeaked. To me, Adams and others, like LaMonte Young and Terry Riley, didn't seem to be Playing the Game, so I sniffed. The later works, however, gave me a context for listening to the earlier ones and made me realize that the new game was worth playing. Shaker Loops by now has become a classic of sorts - part of a declaration of independence from older methods that had begun to constrict and stifle, a willingness to begin fresh.

In 1983, Adams arranged the piece for string orchestra, the version heard here. I prefer it to the original. In the original, you could hear how he brought off the pulsing - valuable, I suppose, for a composer trying to gain technique. The expanded forces, however, definitely increase the electricity of the piece - to me, the work's reason for being. Both versions, however, show the attractions of Adams's brand of minimalism: rediscovery of the excitement of more-or-less regular rhythm; within the regularity, the unexpected surprise jab; the sheer beauty of orchestral sound; the pulsing, buzzing surface, like a consort of insects.

Adams and St. Luke's do okay, but I really want to hear what Nagano would make of it.

Sound in the concerto is excellent, without crossing the line to Hollywood Spectacular, lean in the Shaker Loops.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz