The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Adams Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

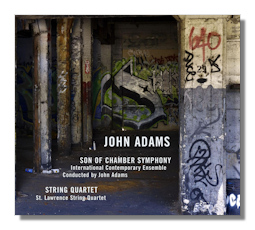

John Adams

Son of Chamber Symphony

- Son of Chamber Symphony (2007)

- String Quartet (2008)

St. Lawrence String Quartet

International Contemporary Ensemble/John Adams

Nonesuch 523014-2 54:00

Summary for the Busy Executive: Neuron dances.

In the Fifties and Sixties, Schoenberg and Webern came into their own, especially in the academies. Webern's music never quite made it out, but Schoenberg's certainly did. You occasionally find his music – and other than his hit Verklaerte Nacht – on concert programs, from all periods of his output. Dodecaphonic serialism came to be taught seriously throughout the country, not just at East Coast conservatories and UCLA, and indeed almost every one of the early minimalists began by following Schoenberg, Berg, or Webern.

John Adams's relationship to Schoenberg has always been ambiguous. On the one hand, he found certain parts of Schoenberg tremendously helpful. On the other, he came to an artistic crisis when he realized that he found Schoenberg's music irrelevant to his own experience as an optimistic American artist growing up post-World War II. As Steve Reich once remarked (one of my all-time favorite quotes), it's hard to feel Angst "in Ohio, in the back of a Burger King," unless of course you work in one. A tension between a largely Schoenbergian technical view (even in a tonal context) and a jazzy, pop-influenced sensibility fascinates. We see Adams's ties to Schoenberg most openly in three works: the Harmonielehre (1985), Chamber Symphony (1992), and Son of Chamber Symphony. The Harmonielehre (study of harmony) comes from Adams's reading of Schoenberg's 1911 treatise of the same name. In the first movement, Adams conceived of "gates," areas of differing tonality or modality that melted into one another, taking off from Schoenberg harmonic progressions. The Chamber Symphony occurred to Adams as he was studying one of Schoenberg's Chamber Symphonies while listening to the soundtrack of the cartoons his son was watching in the next room, and both the Chamber Symphony and Son of do sound very much like that. Schoenberg conceived of a chamber symphony as a symphonic composition conceived for a large-ish chamber ensemble of from 12 to 17 virtuoso musicians, a concept Adams retains. Adams's music, however, couldn't differ more from the dour Schoenberg – European heroism, in which striving usually links with tragedy, vs. American, where striving most often leads to joyful success.

In Son of, Adams, however, tries to find emotional links to Europe and does so with spectacular aptness right from the get-go. The first movement (of three untitled ones) begins with, in the words of the composer,

… a dropping octave "dactyl" rhythm (long-short-short), a musical idea so basic that it ought not to be "owned," but alas is – by the composer of the Ninth Symphony.

Other instruments join in, not fugally as in Beethoven's scherzo, but super-contrapuntally, generating jazzy cross-rhythms. Adams knew from the beginning that Mark Morris, perhaps the most musical of contemporary choreographers, would set this as a dance (Joyride), and so wrote music that a dancer would really want to move to. Each solo instrument retains such an independent character, even in the press of the ensemble, that you can almost see each individual dancer moving in his or her own way across the stage. The movement peters out to the basic pulse, and we enter almost immediately the second movement, an A-B-A' structure. It begins as an arioso, with an arabesque of a line against a steady pulse. The A section falls into two parts: a duet between flute and clarinet, with other reeds joining in with contrapuntal ideas of their own; B consists of a second duet of the same character between violin and cello three octaves apart, with reed babbling and celesta shimmering in the background. Adams views both sections as his equivalent of Wagnerian "endless melody." Activity picks up in the A' section, a skewed version of A that bangs about like a toddler on a sugar high. The finale I call "big-city traffic" music. Adams compares it to the "News" aria from Nixon in China and points out a passage satirizing the opening of his own Harmonielehre, before thinning and ending up on the tap of a wood-block. You end up exhausted and exhilarated.

After a couple of months of listening, Adams's only String Quartet – so far – has flown so high above my head that it's like the airplane you hear in the sky but can't see. The proportions of its two (again untitled) movements are really strange: 21 minutes for the first; almost 9 for the second. Somehow, this alone reminds me of Beethoven, and I'm not giving up. It's one of those works I'll be listening to for years. Its difficulty does not stem from its dissonance. The work, solidly tonal with a high degree of consonance (harmonically, it sounds to my ears like Ravel), sets up other puzzles. I have little idea, for example, where one subsection begins and another ends. I don't know why Adams wanted to write this particular work, beyond fulfilling a prestigious Juilliard commission. Part of the problem comes down to the fact that it doesn't seem to modulate (the main marker of sections in classical music), and the long sections of steady pulsing (although grouped into different rhythms) smooth everything out beyond my ability to make out features – a man without a face, like a Dick Tracy villain. Right now, in the first movement, I run out of gas long before Adams does (somewhere around minute 17), despite some wonderfully inventive string textures. Overall, I hear four main sections: a brilliant, pulsating opening, which brings to my mind the first string quartet of Lukas Foss; a slower section of stops and starts; a scherzo, also with stops and starts; a long fade to the end. As I say, I conk out at 17 minutes and thus miss a lot of the last section, which I nevertheless sense as the deepest part of the movement. Further listening will either toughen me up or kill me.

The second movement opens with more pulsing on leaping and falling octaves, such as we find in many Adams works, including Son of, leading to more brilliant Foss-like counterpoint. That main rhythm of that pulsing recurs throughout the work, leads to various episodes and extensions, and functions almost like the chief theme of a rondo. Fireworks at the end. Right now, however, all the entire quartet means to me is an opportunity to gape at Adams's super contrapuntally-generated cross-rhythms.

Both pieces require virtuosos with fast fingers and fast brains. Both works get them. I can't praise these ensembles highly enough. The precision alone – and precision is a large part of both scores – astonishes, but both the St. Lawrence and the International Contemporary Ensemble do much better than not fall apart: they generate musical excitement. More than that, you sense people having highly sophisticated fun, making the most of their parts while functioning as essentially well-behaved components of a complex system. I don't mean it to sound cold or prim. However, much of the fascination of these scores for me resembles the pleasure I get from looking at exquisitely-made clockworks.

It took me twenty years of very hard work to learn to write at a minimally competent level, and to this day, I continue to slog at it. I start reading John Adams's superb liner notes and I want to cry – so clear, so beautiful, and so seemingly effortless. He has mastered two arts. I wish he'd write more prose, but without reducing his composing. He has only so much time. Nevertheless, I want.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz