The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schoenberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

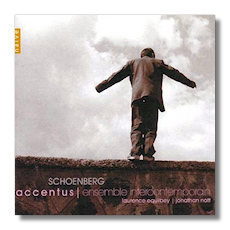

Arnold Schoenberg

Choral Works

- Friede auf Erden, Op. 13, for choir and orchestra ^^*

- Farben (from 5 Pieces for Orchestra), Op. 16/3 (arr. Krawczyk) *

- 3 Volksliedsätze (1929) *

- Friede auf Erden, Op. 13, for mixed choir a cappella *

- Kammersymphonie #1, Op. 9 ^

- Verbundenheit (from 6 Pieces for Male Chorus, Op. 35) *

- Dreimal tausend Jahre, Op. 50a *

- De profundis, Op. 50b *

* Accentus/Lawrence Equilbey

^ Ensemble Intercontemporain/Jonathan Nott

^^ Ensemble Intercontemporain/Lawrence Equilbey

Naïve V5008 64:10

Summary for the Busy Executive: For once, the music, rather than the theory.

Charles Ives once wondered aloud, "Are my ears on wrong?" Every so often, I wonder the same thing about myself. The music I get really excited about, most of my fellow classical-music enthusiasts don't know. I admit I didn't always "like" Schoenberg, but I was behaving like an eight-year-old convinced he hates cauliflower untasted. After all, I had heard only a couple of pieces, not that well performed, and even then it took several revelations before I changed my mind. Furthermore, to this day, Verklärte Nacht, Schoenberg's most popular piece and the one I began with, bores me worse than "Feelings," which is at least shorter. My first breakthroughs were choral. I heard Robert Shaw's On Tour album from the Sixties (RCA LSC-2676, never issued on CD) which offered one of the great Schoenberg performances down to this day: Friede auf Erden, 1911 version. Gurrelieder knocked my socks off. After that, I got to sing both Dreimal tausend Jahre and De profundis, as well as Friede, the 6 Pieces for Male Chorus, and two of the Satiren. Around this time, and probably coincident with the publication of the so-called Schoenberg Edition of the composer's works, Columbia embarked on the "complete" Schoenberg project, but, with few exceptions, the performances did nothing to encourage anybody other than wonks to take up the music. Indeed, the best account for years of the piano concerto I encountered was not the recording by Glenn Gould and Robert Craft, but one given by students on two pianos.

Still, as my mother often told me, every little bit helps. Performances bred other performances and eventually better performances. By the Nineties, the level of Schoenberg interpretation had risen to a level of consistent decency, and now it seems to soar, not just in the choral department either. Standards of playing and musicianship have in general shot up since I first skipped to concert halls, and the Schoenberg idiom has become more and more familiar to players and interpreters. For a long time, many people referred to the Schoenberg "system," rather than to Schoenberg's music, as if the two were identical. Schoenberg's system is embarrassingly skimpy stuff, taken as an intellectual object (if he had only known mathematics, it wouldn't have taken him over a decade to come up with it), and I've always thought of it as a practical (and brilliant) musician's response to the problems of composing in a late, post-Wagnerian Romantic idiom. The system means little apart from the music it produces. Schoenberg, a great thinker about music, fortunately was an even better composer, and really good composers, even tonal composers, have not only followed paths he laid down, but carved their own from the original road. When Hilary Hahn can talk about the "lyricism" of the Schoenberg violin concerto without a single mention of Schoenbergian technical jargon, I'd say we're at the point of taking Schoenberg straight as music.

Most important, a good performance does matter. The Nineties saw a steady trickle of accounts that played Schoenberg musically. In the past few years, we have begun to get a steady trickle of great accounts: Gielen-Brendel, Dohnányi-Uchida of the piano concerto, Huber-Stuttgart and now Equilbey-Accentus on the choral music. Indeed, Accentus raises the bar for everyone, with the best recording of this repertoire available.

Friede auf Erden exists in two forms: the original a cappella version of 1907, and the version with chamber ensemble of 1911. Schoenberg, so convinced of its impossibility for unaccompanied voices, was driven to writing the second version, where instruments could give the singers a little help. In reality, though difficult, it's no more so than Richard Strauss's choral music (which it resembles). Basically, it's the late-Romantic orchestra translated to the chorus – lush, changing textures and lots of subsidiary counterpoint. A chorus of amateurs, led by Anton Webern, first performed the a cappella version in the Twenties. For purists, this has become the version, but I harbor an affectionate preference for the instrumental accompaniment. After all, Schoenberg was one of the great orchestrators, and within his spare instrumentation, he comes up with something gorgeous. Accentus turns in the best account I've heard of the unaccompanied version, so it's nice to report that it hasn't rendered the choir-and-instruments version obsolete. Accentus also comes up with the best account of that version as well. Again, I think it edges out the original. Both performances master the work's architecture. The singing is yummy – superb intonation and a clarity that allows the listener to marvel at the composer's obsession with musical history (references to Beethoven's Missa Solemnis constitute merely one element of a very rich mix) and contrapuntal control.

The arrangement of the "Farben" movement from the 5 Orchestral Pieces comes across as, at best, superfluous. The orchestral original virtuosically shows orchestral colors melting into one another at the level of the melody line. Schoenberg called the effect Klangfarbenmelodie, sound-color-melody. It's possible to only a limited extent in voices, and the arranger, Krawczyk, really doesn't exploit even this reduced possibility. He relies mainly on ostentatiously audible breathing as his main effect, which might have worked neatly, had he also come up with something more relevant. Even Accentus can't save this. A Mills Brothers arrangement has more of the necessary wit than this does.

If you harbor doubts about Schoenberg as a great composer, the 3 Volksliedsätze (3 folksongs) should drive them out, and he never even gave them an opus number. In 1928, the German government commissioned these beautiful gems, and Schoenberg selected the texts from a collection of medieval folk poetry. The settings could have been written by Brahms in his final period, a combination of meditative funk and luxurious tonal counterpoint that results in a good cry over lost things. If you like something like Brahms' "Im Herbst" from the opus 104 or "O süsser Mai" from Op. 93, these should appeal to you.

"Verbundenheit" (solidarity), the last of the 6 Pieces for Male Chorus and my favorite of the set, plays off the German Männerchor tradition, especially as practiced by Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Schumann, with their fondness for the dark, rich sonority of men's voices. It's the vocal equivalent of massed horns. It may even be serial, for all I know, but the outstanding feature of it comes across as barely-related chords that create a powerful forward movement. Vaughan Williams and Debussy create similar effects with their unusual harmonic progressions. You can't call it atonality, and you can see why Schoenberg himself hated the term. Schoenberg stretches tonality to its limit, but that counts for less than creating beauty. It's like listening to a sequence of "magic" chords.

Dreimal tausend Jahre (thrice a thousand years) and De profundis, on the other hand, definitely fall into the serial category. They constitute the last pieces Schoenberg composed to the finish. He wrote them both in the aftermath of the founding of the State of Israel. Dreimal sets a poem by Schoenberg's publisher, one Dagobert Runes, about a Jew returning to Palestine. It's not a great poem, and Schoenberg may have set to work as a way of keeping Runes sweet. Nevertheless, the composer came up with a masterpiece, strongly related to the Brahmsian Romantic part-song, yet with a more philosophical tone. Both works also come from a time when Schoenberg wanted to forge strong connections from traditional tonality to his new music. Actually, I have long thought that Schoenberg was so steeped in post-Wagnerian harmonic practice and voice-leading that, like Stravinsky in his serial period, he never ever got completely away from tonality. I tend to hear the works of the late period as tonal – so, for me, Schoenberg succeeded – but as tonality happening at high speed. De profundis, a setting of Psalm 130, sets up an opposition between solo and duo lines and rhythmically-declaimed speech (Sprechstimme), to create a powerful image of a cantor and his davning flock.

The CD also includes a magnificent performance of the first Chamber Symphony by the Ensemble Intercontemporain led by Jonathan Nott – why, I can't tell you. Nevertheless, I've not heard a better, although I have encountered some as good. Still, I would have preferred the complete 6 Pieces for Male Chorus or, dare I say it, the Kol nidre.

Equilbey and her troops have swept away my previous standard, Huber and his Southwest German Radio (Stuttgart) Choir. Huber did well, don't misunderstand me, but there lingered about his readings the air of preparation and blueprint. Equilbey gives you music. Obviously, she has trained her singers and players – superb intonation, diction, tone, etc. – but they no longer sound as if they're taking a test. Even if you currently hate Schoenberg's music, you should give this disc a try.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz