The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Beethoven Reviews

Brahms Reviews

Haydn Reviews

Mendelssohn Reviews

Verdi Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

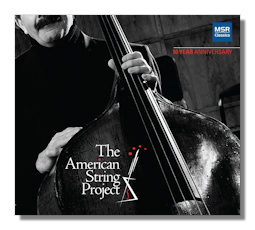

From String Quartet to String Orchestra

10 Year Anniversary

- Felix Mendelssohn:

- String Quartet #4 in E minor, Op. 44 #2

- Ludwig van Beethoven:

- String Quartet #8 "Rasumovsky", Op. 59 #2

- Giuseppe Verdi:

- String Quartet in E minor

- Franz Joseph Haydn:

- tring Quartet #66 in G Major, Op. 64 #4

- Johannes Brahms:

- String Quintet #2 in G Major, Op. 111

The American String Project

MSR Classics MS1386 141:12 + 25:25 (2CDs+DVD)

Summary for the Busy Executive: "Bless thee, Bottom! bless thee! thou art translated."

Composers haven't written a lot of chamber music for bass fiddle. You might think of Schubert's "Trout" Quintet before your mind goes blank. Imagine the frustration of Barry Lieberman, former associate principal bass of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and lover of chamber music. Because there's only so many times you can play the "Trout," he began to arrange string chamber works for string orchestra. His wife, Seattle Symphony concertmaster Maria Larionoff, had wanted to establish a conductorless ensemble, so they combined their aims into the American String Project, essentially a festival that draws on the talents of superb colleagues (their résumés would amaze you). This CD records their "Leadership" gets assigned by the piece, so a leader (responsible for interpretation, often arrived at collaboratively) of one score can very well find himself or herself among the mass for another.

Arranging, say, a string quartet turns out not such a breeze. You can't just double the cello line with the bass fiddle, just as you can't translate from Greek to English word by word and expect something more than a soliloquy by Tarzan. Lieberman, at his best, in almost every case takes the score apart and reassembles it with the large ensemble in mind. Furthermore, some works suit the process better than others. Lieberman has at least one miss on this particular CD, but I blame his choice of score. A work at the end of this process is not simply a super-sized quartet with a slightly deeper voice: its original nature changes, often in surprising ways.

Against initial expectation, I consider the Mendelssohn String Quartet #4 the least successful of Lieberman's ministrations. Mendelssohn certainly knew how to write for strings, and his quartets – too little known – have both wide emotional range and elegant craft. However, to me Mendelssohn had one of the sharpest senses of any composer of the essential characteristics of an instrument or of an ensemble. This score works as a string quartet. I miss in the inflation to a larger medium the quartet's intimacy and flexibility. The new incarnation reminds me of a hippo trying to escape a tar pit.

I stress that you often don't know what you'll get. The first movement of the Beethoven "Rasumovsky" #2 becomes a mini-"Eroica," especially with its opening heavy chordal strokes and, of course, its identical meter to the symphony's opening. According to Czerny, Beethoven composed the quartet's second movement after the inspiration of a starry night and thoughts about the music of the spheres. The expanded ensemble, particularly with the added depth of the bass fiddle, makes it easier to imagine such a possibility, let alone the sky on a quiet night. I find suggestive the similarity of Beethoven's avowedly spiritual music (the Heiliger Dankgesang of the quartet, Op. 132, for example) and his slower-moving Nature music (like the Andante and the finale of the "Pastoral" Symphony). Apparently, for Beethoven, God indeed formed and informed Nature. The oft-noted secondary theme of the third movement (Mussorgsky used the same one in Boris Godunov's coronation scene – Slava!) sounds like something Rimsky-Korsakov might have turned to, had he written a work for string orchestra (he may have, for all I know), while the fourth movement reveals itself in Lieberman's arrangement as an ancestor of the Mendelssohn Octet. So many of its ideas whisper in the background of the later score. This should surprise nobody, since Mendelssohn studied assiduously the music of Beethoven's middle and late periods.

The Haydn also benefits from the more-opulent sonority as well as the opportunities (which Lieberman takes advantage) of contrast between solo quartet and the massed strings. We wind up with a lovely string serenade, one that might well occasionally substitute in a program slot for Eine kleine Nachtmusik.

The Verdi benefits as well. I don't know why, but Verdi's string quartet usually appears as an afterthought among chamber-music fans, but until recently, Verdi himself figured as an afterthought among people who don't listen to opera. Other than the German tradition, Modern writers considered opera a lesser form, to some extent because of its popular appeal, but also because it doesn't yield much to traditional musical analysis, developed mainly for German music, after all. It's as if Verdi were all tunes and no brains. However, in addition to his experience in the Italian theater, the composer had received thorough conservatory training and shows it off in the quartet. If you expect melody to a guitar-like accompaniment, the quartet will surprise you. First, it avoids the clichés of 19th-century quartet writing. Its ideas and their treatment arise from an individual mind. The opening movement, as contrapuntally gnarly as Beethoven, always seems about to break out into fugue, while the last movement is indeed a fugue. I love Verdi's fugues, rare as they are. The last movement sounds a bit like the "Libera me" from the Requiem, only upside-down. Again, the heft of Lieberman's arrangement gives the quartet a grimmer tone, turning it into something you need to pay attention to. The orchestral version would make a worthy addition to a program. I'd love to hear how the strings of the Cleveland Orchestra would do.

Although until recently an apostate on the matter of Brahms's string quartets (I finally heard some really good performances in really good sound), I've loved his major instrumental chamber music. The two string quintets and sextets have remained special favorites. Nevertheless, in their original form they challenge the clarity of an ensemble brave enough to take them on. Brahms aims for a rich sonority suggestive of an orchestra as well as for rich counterpoint, and the texture can become a musical thicket. Lieberman and the ensemble (led in this instance by Stephanie Chase, also an occasional arranger) had work to do. Despite Lieberman's success in clarifying the music, the expansion loses something essential to the original – a sense of striving, of saying more than you thought possible. A masterpiece remains a masterpiece, but again becomes something lighter, a cousin to Tchaikovsky's Serenade in C.

The CD set also includes a short DVD documentary on the American String Project where you meet the principals and some of the players. The documentary shows a sociable group, having a good time with hard work and the reward of successful performance. They rehearse and perform excerpts from Prokofiev (String Quartet #2), Robert Schumann (String Quartet #3), and Manuel de Falla (7 Canciones populares españolas).

The performances – all live – reach at least a professional level, with some of them better than that: the Haydn, Verdi, and Brahms. However, the dryness of the Nordstrom Recital Hall in Seattle works against the players and, in my opinion, kills the Mendelssohn. I don't ask for studio quality, just a livelier venue.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz