The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Clementi Reviews

- Czerny Reviews

- Gershwin Reviews

- Godard Reviews

- Kreisler Reviews

- Medtner Reviews

- Moscheles Reviews

- Sibelius Reviews

- Thalberg Reviews

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

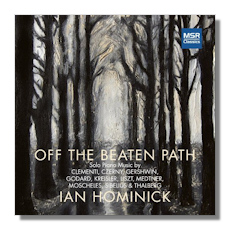

Off the Beaten Path

Solo Piano Music

- Muzio Clementi: Sonata in B Flat "Magic Flute", Op. 24/2

- Benjamin Godard:

- Au matin, Op. 83

- Second Valse (arr. Rabinof)

- Sigismond Thalberg: Nocturne in B, Op. 51 bis

- Ignaz Moscheles: La petite babillarde, Op. 66

- Fritz Kreisler: Rondino on a Theme of Beethoven (tr. Godowsky)

- Franz Liszt: Die Lorelei

- Carl Czerny: Etude melodieuse, Op. 795/3

- Nicolai Medtner: Piano Sonata #6 in C minor "Fairy Tale" Op. 25/1

- Jean Sibelius: Romance, Op. 24/9

- George Gershwin:

- Novelette in Fourths (arr. Zizzo)

- Melody #40 (arr. Rabinof)

Ian Hominick, piano

MSR Classics MS1341 TT: 67:46

Summary for the Busy Executive: En salon.

As a know-it-all teen, I would have sneered at this program (except for the Clementi and the Gershwin) as cheap salon music. A musical snob, I haven't changed all that much, but I did realize that I didn't want to hear Beethoven's Missa Solemnis or Wagner's Ring all the time, mainly because I didn't inhabit the empyrean all the time and thought that music should address as much of my life as possible. Furthermore, I discovered the joys of amateur music making, especially at home. My Aunt Ida used to play this kind of stuff, most of it by no means as good as anything here. Besides none of these items is exactly "The Maiden's Prayer" or "Pale Hands I Loved Beside the Shalimar," and if the genre's good enough for Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Grieg, it's certainly good enough for me.

Most of these pieces appeared in the Nineteenth Century, the salon's golden age. At the upper end of the tonier salons, you get the likes of Chopin, Schumann, Grieg, Mendelssohn, Elgar, and Liszt, who also turned out major piano works. However, there are a host of decent composers who produced essentially modest pieces and nurtured no ambitions to scale Olympus. As usual with such programs, you will probably like some pieces more than others. What stuck with me follows.

Virtuoso pianist, publisher, and piano maker, Muzio Clementi lived a very long life, from years before Mozart to years after Beethoven. He wrote in the Classical style. His composing reputation has descended from Rival of Mozart to Kiddie Composer, since beginning pianists tackle his sonatinas. He has had the occasional champion – most famously, Horowitz who programmed and recorded his sonatas. This sonata is ironically nicknamed "The Magic Flute," since the main theme of the first movement is the same as that of the main theme of Mozart's overture to Die Zauberflöte. The irony – and a bitter one at that – lies in the fact that Clementi composed his sonata years before Mozart had composed his overture. We know that Mozart had heard this sonata. Not to put too fine a point on it, Mozart appropriated the theme. However, his treatment of it leaves Clementi in the dust. He unleashes that theme, and in art, who does it first matters less than who does it better. Nevertheless, the Clementi isn't exactly treyf. It bubbles and sparkles, particularly its glittering finale.

Benjamin Godard, on the other hand, died in his 40s. His lovely "Au matin" contains the seeds of Debussy, with a Tchaikovskian sense of melody and color. Sigismund Thalberg, one of Liszt's virtuoso competitors, makes a good showing in his Nocturne. While nowhere near Chopin and Liszt, especially at their best, he nevertheless manages a convincing Chopinesque poetic statement. Moscheles, yet another virtuoso, contributes a zany morceau, "Le petite babillarde" (the little chatterer), where the piano babbles a mile a minute. Most musicians these days look on Carl Czerny, "Beethoven's most famous pupil," as a pedant, probably because of the exercises and etudes he wrote. The "Étude melodieuse" gives the lie to this picture with a wonderful melody that shows Czerny capable of tender poetry.

Medtner's "Fairy Tale" Piano Sonata interests me more than moves me emotionally. The piano writing lies very close to Rachmaninoff's, Medtner's friend and contemporary. The sonata aspects of it don't mean all that much. It resembles more Rachmaninoff's Études-tableaux, but without the latter's sense of drama or gift for melody. The piano textures are almost unrelentingly thick, as if Medtner needs to have every finger moving.

Far less ambitious and far more successful is Sibelius's Romance. We don't think of Sibelius as a piano composer or even as a chamber composer, outside of the string quartet, but he wrote a ton of both. Piano music was one way to pay the bills. This little gem of a score features a melody that seems to capture Sibelian lyricism and feeling for nature in a small space.

Gershwin wrote far more than he published. Indeed, his brother Ira kept releasing songs well after the composer's death – songs that Gershwin had stowed away in the trunk. He once shocked Poulenc, a composer who agonized for years over certain scores, by reporting that he wrote "six or seven songs a day, just to get the bad ones out of my system." He also kept notebooks and tune books, which scholars have in recent years brought to light. It may interest the Gershwin fan like me to see chips from the composer's workshop, but most of these things are just kernels of ideas rather than strong compositions. Some are even composition exercises – homework that Gershwin undertook from his studies with various teachers. Gershwin had tremendous natural talent, but he also seriously studied. The Novelette in Fourths, a hybrid of Debussy's Golliwog and Joplin's Maple Leaf, takes a melody and shadows it a fourth below, for a "Chinese" effect. The Melody #40 is a melody with harmony, 32 bars, the beginning of a piece intended for a violinist friend. Sylvia Rabinof arranged it and greatly expanded it for pianist David Glazer (see my review of the album), I don't think too successfully. For one thing, it's very easy to tell her contributions from Gershwin's, and Gershwin's are far more distinguished.

Ian Hominick, a pupil of Earl Wild, among others, plays impetuously and attractively. He's better in the fast pieces than in the slow ones. The quick and lively seem to engage him more. On the other hand, "Au matin," "Étude melodieuse," and Sibelius's "Romance" come off pretty well, so perhaps I'm blowin' smoke. The repertory recommends itself as off-the-beaten-path, and a lot of times it rewards you for your willingness to take the road less traveled. Recommended for those times when Parsifal is just too much.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.