The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Debussy Reviews

Martin Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

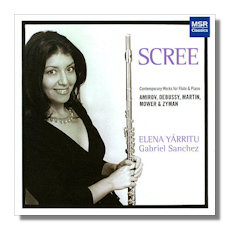

Scree

- Samuel Zyman: Sonata for Flute & Piano

- Claude Debussy: Claire de lune (arr. Moyse)

- Fikret Amirov: 6 Pieces for Flute & Piano

- Frank Martin: Ballade

- Mike Mower: Flute Sonata #3

Elena Yárritu, flute

Gabriel Sanchez, piano

MSR Classics MS1277 61:13

Summary for the Busy Executive: Really good flutist in a fairly strong program.

Through the luck of the draw, really, I've found that I've recently reviewed a fair number of solo recital discs. By no means have I liked all of them, and since I hate writing an unfavorable review ("you mean I have to listen to this AND take the time to write a review?"), I've passed such issues along to others. On the other hand, I've heard some amazing players, not all that well-known to the classical-music audience. I think especially of the bassoonist Benjamin Coelho, the Hot Club of San Francisco, the Imani Winds, violinists Mela Tenenbaum and Ray Chen, Le Charbonniers d'Enfer, and the American String Project. In all, I've come out ahead. The golden ages of flute repertoire are the Baroque and the Modern. In the two most popular eras – the Classical and the Romantic – good stuff comes along in dribs and drabs, so most of the repertory items remain rather obscure. Elena Yárritu has assembled at the very least an interesting program, often a great one. Outstanding items include the Zyman flute sonata and the Martin Ballade (a classic). Samuel Zyman, a Mexican of Jewish family now teaching at Juilliard, contributes a vigorous work, which by rights should become something every flutist should know. Rhythm is its outstanding feature, and the players here attack absolutely together and with complete control. Zyman has written that when he studied composition, roughly the Seventies, the predominant mode was a-rhythmic. He reacted against it, and I applaud him for it. Arrhythmia bothers me much as or more than atonality bothers others. I can take a bit of it, but an entire movement of it, and I start yelling at myself. I'm an American. For heaven's sake give me a beat I can feel. Rhythm shapes time and the rhythmic definition which shows the shape needs a tactus. Otherwise, time-fabric becomes ooze or smear, and I don't care how complicated the rhythmic relations are. If there is no relating beat, 5 against 7 means nothing, because you usually can't tell the groupings anyway. Music becomes something heard and felt to something seen – the printed score or the conductor's downbeat. Zyman's rhythms are neither easy nor particularly Latin-American, but they grab you, even at slow tempos.

Frank Martin (pronounced Mar-TAN; he's Swiss), although he had some training, mainly taught himself, and he had an individual mind as well as talent. He got interested in Schoenberg's dodecaphony, although he rejected several fundamental dodecaphonic principles, and came up with a "harmonic dodecaphony," a near-oxymoron. His music hovers on the edge of recognition – a shame, because there's some very powerful stuff out there in almost every genre. He wrote six pieces he called Ballades, for soloist and accompaniment: alto sax, flute, piano, trombone, cello, and viola. All run to one movement, full of high contrast. Except for the piano Ballade, all of the series exist as solo instrument and piano or solo instrument and instrumental ensemble. To the extent that the title leads you to expect something feathery and dreamy, it leads you down the garden path. This is a piece of high drama, all too rare in flute literature. It has the weight of something by Bach.

I rolled my eyes when I saw "Claire de lune," even though the arrangement was by Marcel Moyse, a great flutist and a musician of the highest taste. I've heard so many bad arrangements of this, so sickeningly sweet, leave it to the pianists, I thought. However, Yárritu won me over, not least because of a lung capacity that might be able to move sailboats. There were phrases that seemed impossibly long, and yet I couldn't tell when or even if she ever took a breath. Further, the reading was one which seemed utterly "natural," perhaps the toughest thing a musician can do. The piece became affecting rather than sentimental, as the composer probably intended, with just the right amount of coolness – a slight frisson in the night breeze.

The Azerbaijani composer Amirov gives us a charming suite, reminiscent of Khachaturian, British Mike Mower a slight "soft jazz" sonata, sprinkled by hesitant flirtations with avant-garde instrumental techniques. Compared to the Zyman and the Martin, both scores are pleasant rather than necessary. Mower gets the inspiration for his sonata from geological formations (the finale title gives the album its name), always a risky strategy. The music may not evoke from others what it does from him. So it's probably a good idea to make sure that the score hangs together musically. Of course, coherence is relative. Mower's is less than Martin's, but it's still probably enough.

Yárritu gives us different colors for different works. She's nervous and brittle in the Zyman, silvery in the Debussy, and weighty in the Martin. She and pianist Sanchez do best in the best works, possibly because more is at stake. They are uncannily together in the Zyman and Martin. I quibble only that occasionally the flute seems under-recorded. I got used to it.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz.