The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Dupré Reviews

Franck Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

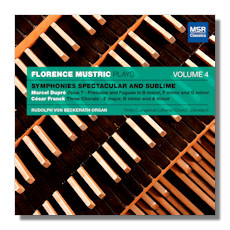

Symphonies Spectacular and Sublime

Organ Music, Volume 4

- Marcel Dupré: 3 Preludes & Fugues, Op. 7

- César Franck: Chorales #1-3

Florence Mustric, organ

MSR Classics MS1273 66:01

Summary for the Busy Executive: Great repertoire beautifully played, beautifully recorded.

The organ got its hooks into me early. As a tot, I wanted one. In general, I love the organ and organ music but could do without organists, who generally give me a wall of smothering, undifferentiated sound. As Stravinsky once remarked, "The monster never breathes." Or, at least, many organists seem to play that way. I should say first that most big-name organists leave me cold. E. Power Biggs interested me mainly because of his repertoire. I never understood the adulation surrounding Marie-Claire Alain, Helmut Walcha, or Daniel Chorzempa. The one who gets me humming is Simon Preston. Nevertheless, most of the organists who've thrilled me play in local churches. Don't get me wrong: I've heard plenty of lousy players in churches as well. Organist Florence Mustric presents a program of two stellar representatives – one Romantic, one Modern – of the French organ school: César Franck and Marcel Dupré.

Written in 1890 and Franck's final work for organ, the 3 Chorales represent the acme of 19th-century organ composition. Only the Brahms 11 Chorale Preludes, Op. 122, breathes the same high-flown air. I've always thought Franck at his best in his organ music. Of course, I say this without knowing his oratorios at all, and I've read raves about them. Here, Franck perhaps pays homage to J.S. Bach, although the textures are far more lush. The first chorale takes a lovely andante theme and develops it in a unique form that takes on aspects of fantasia, variation, and sonata. The stern second, perhaps the best known, works with three themes: one that first appears as a passacaglia bass line; a second, usually thought of as the chorale proper, and which sounds as though it combines well with the passacaglia bass (it does); a third which seems to smile from heaven and which usually dissipates tension. The first two ideas get considerable development. For example, the first theme becomes the subject of, among other things, a passacaglia and a fugato. The end of the chorale leads you to expect a glory of the organ's full power, but Franck releases the pressure with a fine diminuendo that leads us to the song from heaven and the piece ends raptly.

The third chorale I have always considered a bit too episodic, where Franck's tendency to sprawl begins to emerge. It opens as a toccata, the blueprint of which seems fairly obviously Bach's Toccata in d. Massive chords punctuate rapid finger-work. However, where Bach's toccata seems of a piece, Franck's toccata idea serves mainly as a bridge to lyrical sections: the chorale tune itself, two lyrical sections (the second gorgeously sinuous), and the ramp-up to the finale, where the chorale tune emerges triumphant.

If Franck represents one strain of the French organist-composers – the mystical and lyric – Camille Saint-Saëns and Charles-Marie Widor represent the virtuosic. Marcel Dupré's Op. 7 cleaves more to the latter. Dupré studied with Widor, who lived to 93. Widor, incidentally, initially stunned his pupils by insisting that they knew Bach's organ music, as a requisite to improvisation. It may shock us now that at one time organists didn't know Bach's music beyond a couple of pieces. A virtuoso with a technique comparable to Horowitz's (except Horowitz never had to contend with organ foot-pedals), Dupré wrote a great deal of music that featured technique. Some of it amounts to mere display. But much, while difficult, succeeds as music, like the Op. 7. The first prelude descends in a direct line from the famous Widor Toccata – the hands scintillating over the manuals, while the pedals sound out a broad melody. The fugue uses a loopy arpeggiating subject – loopy in the sense that if all voices arpeggiate at roughly the same time, it becomes hard for the ear to separate the voices. However, this happens only once in the fugue, and briefly at that.

The second prelude and fugue dials back. A lovely chromatic cantabile theme receives support from pedal points in the bass and quiet arpeggios in alt. Just when you think Dupré might be giving the soloist a break, he makes the poor dear perform the arpeggios on the pedals as the melody takes flight above. The melody becomes the fugal subject.

The third prelude, a gigue, seems fairly straightforward, until Dupré gives three- and four-note chords to the feet. I don't know how this is even possible. It may well have been what led Widor, a considerable virtuoso himself, to declare the piece unplayable, and indeed for a while only Dupré played it. The fugue, another gigue, is a whirligig of counterpoint. The organist gets to play the subject forwards, backwards, upside-down, and (I think) upside-down and backwards. According to the liner notes, this fugue was Dupré's favorite encore.

Those in the know will recognize Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church as a Cleveland, Ohio, landmark. The organ, modeled on baroque instruments by Rudolph von Beckerath of Hamburg, is one of the finest in the area, which boasts stiff competition. It would be a terrific instrument for Bach, and it comes through beautifully in the Franck and Dupré. Mustric reins in the sprawl of Franck and delivers beautifully coherent performances. She conquers all of Dupré's technical challenges while keeping the music. The Duprés sound not difficult, but fun.

I must also praise the recording itself, to my mind the best, most natural recording of an organ I've heard – not over-reverberant, but what you would hear in a modest-size church. Alan BISe, of the Cleveland boutique label Azica, "produced, engineered, and mastered" the program. He also produced and edited the best, most natural recording of a string quartet I've heard: John Adams's complete string-quartet music on Azica. I'd hit the Internet and buy both.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz