The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Shchedrin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Blu-ray Review

Blu-ray Review

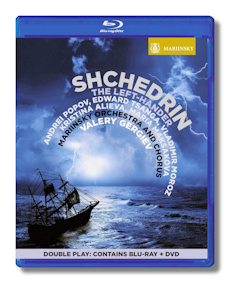

Rodion Shchedrin

The Left-Hander

- Kristina Alieva, soprano The Flea

- Maria Makasakova, mezzo soprano Princess Charlotte

- Andrei Popov, tenor The Left-Hander

- Vladimir Moroz, baritone Alexander I/Nicholas I

- Edward Tsanga, bass Ataman Platov

Mariinsky Orchestra & Chorus/Valery Gergiev

Mariinsky Blu-ray/DVD MAR0588 2Discs 119m LPCM Stereo DTS

Also available on SACD MAR0544:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

Nikolai Leskov lived from 1831 to 1895 and wrote the Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which provided the basis of Shostakovich's opera, of course. The author's later novel Lefty: The Tale of Cross-eyed Lefty from Tula and the Steel Flea is seen as Leskov's finest work. It's the compelling result of an imaginative narrator who prizes the new and quirky. Wordplay and satire are at its center. One is reminded of the apparently rule-less drama of Dario Fo by Rodion Shchedrin's (born 1932) opera here presented on both DVD and Blu-ray in its production by the Mariinsky in St Petersburg in 2013 under Gergiev on the Company's own label. In fact, Shchedrin's two act opera (to the composer's own libretto after Leskov) was written specifically for the opening of Mariinsky II, and its score is dedicated to Valery Gergiev.

Yet to have emphasized the absurd and made a spectacle of it in the opera or in its staging would have risked drawing the teeth, lessening the impact, of the satire and the subtleties that exist in the work. So – for all the gestures, the gauche mannerisms which color the production, and which are captured well in this video – detachment is needed. And offered here to make the moral impetus work more effectively. So it is.

The Left-Hander is a kind of political satire… Tsars Alexander I and Nicholas I and the British royal establishment are at its core. To some extent the folly of the former is contrasted with the stolid nature – at least as often perceived – of the latter. The way in which absurdity and buffoonery are handled and how acceptance or resistance can lead to implicit tragedy is almost effortlessly examined.

Most important, perhaps, of all is the central role, the left-handed rogue or villain (he can be seen as both). Played in a forward yet not over-grotesque way by tenor Andrei Popov, his personality and behavior are suggested by Leskov and Shchedrin as central to understanding the Russian character – in the way that Falstaff is the English. Able to laugh at himself, as crafty as he is resourceful; illiterate; a lover of alcohol; and with a disdain for (the greater good of) humankind. He seems to embody the interplay between power for power's sake and an almost "negative" genius of invention.

The music is tonal with little acknowledgement of experiment. It's full of gesture and easily-recognizable tropes and passages set to support large-scale choreography across the broad stage, whose set is minimal yet communicative of Russian starkness and the ways in which that country's people are typically conceived as responding to it… lots of blues and grays, snowflakes, steps and large flat surfaces; light available from the expanses that are suggested, yet rarely really taken advantage of; clean unragged yet undemonstrative costumes.

One of the strengths of this production is that the characters do not rush. Stage "business" never intervenes. They have ample time and scope to reveal the absurdities which are essential to this work. Shchedrin and Gergiev have produced an unself-conscious parable almost redolent of Biblical or even Greek solemnity. Yet which is not a mockery of itself… the perfect balance for effective satire. At times it does seem as though the music is really "following" the action and text, rather than that it has been melded with it to create something truly special in the way that Shchedrin's (Russian) predecessors were so expert at doing. In other words, one waits for what the action, dialogue and disposition of performers on stage will do next, rather than being swept up with essentially musical tensions, releases and progressions.

These are not substantive criticisms, though. For Shchedrin is a definitely theatrical composer. In eschewing musical gestures for their own sake (the set piece, audience-addressing ensembles, tutti for effect, for example) he re-inforces further the very essence of the balance between the surreal and why we should care about it – much in the way that Janáček does. This is not a ground-breaking opera. But neither is it one which should be consigned to the category of "competent" or "perfunctory". Nor indeed is it to be seen as some cold reaction to events in a country whose polity changed immensely between Leskov's time and Shchedrin's, whose own political allegiances make interesting study.

Neither light (superficial) nor overblown, it's music for which some listeners will make a conscious effort to find continuity of substance. But – always as professional as insightful – the whole operatic convention is given technically solid and diligently imaginative service by Gergiev, his singers and orchestra. Their strongest suit is the traction they seamlessly elicit between understatement and the projection of Leskov's intent in such a way that Shchedrin clearly re-inforces it and fills it out in a truly musical way. There is no place for exaggeration, winks at the camera or declamation expecting a response. Indeed, for much of the time, it's as though the singers as actors are performing for themselves. And this makes the very most of the composer's conception.

The sound quality on the DVD and Blu-ray disks is good. They rightly capture the acoustic of the Mariinsky II spaces, which is neither overwhelmingly vaulted nor unduly concentrated. The booklet in Russian, English, French and German could have been more extensive: there's brief background only. In the end, a large factor in appreciating The Left-Hander is how well the work's superb irony and deadpan wit can be perceived and understood by those unfamiliar with Shchedrin's brand of humor, and his purpose. This production and its expert filming certainly allows us to see facial gesture and body language whenever these serve such an appreciation. Subtitles are available in six languages, which helps immensely. This is clearly a work which will shine in a niche, in the particularity of its genre. Yet it was performed, and has been captured on film, very well. It makes an interesting, if not a game-changing, addition to the catalog.

Copyright © 2016, Mark Sealey