The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Shchedrin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

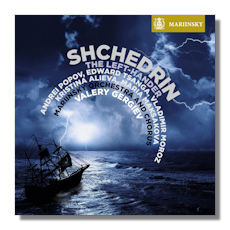

Rodion Shchedrin

The Lefthander

- Levsha (The Lefthander) - Andrei Popov

- Ataman Platov - Edward Tsanga

- Alexander I/Nicholas I - Vladimir Moroz

- The Flea - Kristina Alieva

- Princess Charlotte - Maria Maksakova

- Andrei Spekhov - English Underskipper

Mariinsky Orchestra & Chorus/Valery Gergiev

Recorded Live at the Mariinsky II, St. Petersburg, Russia July 27 &28, 2013

Mariinsky SACD MAR0554 2Discs 59:13+60:14

Rodion Shchedrin (b. 1932) is still active in his eighties and still producing important works that add to his significant legacy. This new composition, the two-act, nearly two-hour opera The Lefthander, was premiered on July 27, 2013 in a performance at the Mariinsky Theater II in St. Petersburg, Russia, led by Valery Gergiev, to whom the composer dedicated the work. Shchedrin fashioned his own libretto after the novel The Tale of Cross-eyed Lefty from Tula and the Steel Flea by Nikolai Leskov. This recording on the Mariinsky label is derived from the premiere performance as well as one given the following night at the same venue. Thus, depending upon your assessment of Shchedrin and this opera, it could well be quite an historic document. Incidentally, the work is actually titled, Levsha ("The Lefthander"), but for this recording and the English premiere at the Barbican in London in November, 2014, "Levsha" was dropped.

Levsha, the main character, is a gunsmith who is sort of a high-tech wizard living in early 19th century Russia. After the Tsar returns from a trip to England where he was presented with a mechanical flea that can dance and recite the alphabet, Levsha is assigned the task of improving on this clockwork wonder to demonstrate the Russians are better craftsman than the British. He succeeds: horseshoes are added to the flea and it can now recite the Russian alphabet and dance the Russian Barynya. The British are greatly impressed and try to convince Levsha, who has come to England with the flea, to remain there and work with them. But he refuses the offer and returns to Russia where, despite his great success, he resumes his humdrum existence and dies in total obscurity. The story is a comedy, but one that becomes a tragedy of sorts, its laughs turning to tears. Levsha is more than a victim here, as Shchedrin's quotations of religious music from J.S. Bach's Passions and from Russian Orthodox sources make him into a sort of martyr.

Shchedrin's score features no knock-out arias or duets and no catchy themes, but it is very colorful and not particularly difficult for listeners accustomed to the operas of composers like Thomas Adès, Osvaldo Golijov, or John Adams – different as their styles are from Shchedrin's arguably more eclectic one. Thus, it's approachable in many ways but hardly as lush or lyrical as, for instance, Jake Heggie's Moby Dick, to cite just one recent and highly successful opera. The Lefthander may well have more in common with two operas from nearly a century ago, the pair by Shostakovich – The Nose (1928) and Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1934). The Nose features a similar brash comedic style, while the libretto for Lady Macbeth was fashioned after a novel by none other than Nikolai Leskov.

Shchedrin's orchestration occasionally calls Shostakovich's to mind as well. Speaking of orchestration, Shchedrin employs some unusual instruments in his score, including domra (a type of balalaika), duduk (a very ancient Armenian flute made of apricot wood), and bayan (a Russian version of the accordion). He often obtains an exotic sound, too: try Act I's Ataman Platov's Story or the Act II orchestral interlude, Know How. But not only is his orchestration consistently engaging, his choral writing is deftly imagined as well. Indeed, try the penultimate section The Ordeal in the Infirmaries. At times the style here reminds me of the darker moments of Shostakovich's Stenka Razin or his non-choral Eighth Symphony. Not that Shchedrin composes under the spell of Shostakovich – for the most part he writes in his own quite individual style. True, at times he can sound like Shostakovich, or even Mussorgsky, but those moments are relatively few. In the end, one can fairly assess that Shchedrin has produced in his old age a work of significance, maybe of greatness, and his admirers and those with an interest in contemporary opera ought to take note. But what of the performances here, you ask?

The singing is very excellent, especially in the roles of Levsha as portrayed by Andrei Popov, and the Flea, sung by the utterly spectacular Kristina Alieva. She sings impossibly high notes way up in the stratosphere throughout the opera and her performance, both musically and dramatically, is simply stunning. The rest of the cast is quite good, though Maria Maksakova as Princess Charlotte divulges a vibrato that can turn into wobble in places. Still, all the singing is more than adequate, and the orchestra performs with commitment and accuracy under Gergiev, who seems very attuned to Shchedrin's style.

What many of you are probably wondering now is: is the work a masterpiece? Maybe a flawed masterpiece, maybe even a full-blown masterpiece. We'll just have to spend more time with the opera to grasp all its subtleties and challenges. If I have to make a judgment, then I'll opine that this is perhaps a minor masterpiece that may well go on to gain some currency with opera companies overtime. I had hoped initially that a video of this performance would soon appear, as I suspect the opera would be much more effective in that format. But I wouldn't hold my breath, because in the past the Mariinsky label has tended to release performances in either SACD format or video (DVD or Blu-ray), but not in both. The sound reproduction is very good. Full texts are provided. As suggested above, if you're a Shchedrin admirer or someone interested in contemporary opera, this release is eminently worth your attention.

Copyright © 2015, Robert Cummings