The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Webb Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

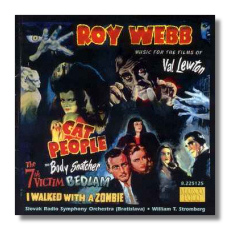

Roy Webb

Music for Scores for the Val Lewton Films

- Cat People

- Bedlam

- The Seventh Victim

- The Body Snatcher

- I Walked With a Zombie

Slovak Radio Orchestra/William T. Stromberg

Marco Polo 8.225125 69:53

Summary for the Busy Executive: "I wants to make your flesh creep." – Dickens's Fat Boy

Of the major film composers for Hollywood between the world wars – including Korngold, Rózsa, Waxman, Tiomkin, and Herrmann – Roy Webb has the dubious distinction among film-music buffs as "the forgotten man," despite the fact that he scored over 300 films, I believe almost all of them for RKO. As such, he became colleagues with Max Steiner and Bernard Herrmann for the times when they worked exclusively for the studio. I first became aware of him with the dawn of my interest in film noir. I noticed that many of my favorite pictures in the genre all had wonderful music by Webb. Nevertheless, Webb was the complete professional and scored movies of all types: comedies, action, Westerns, musicals (the stuff not the songs), period pieces, and horror.

In some ways, I understand his obscurity. His film scores are rigorously efficient. They contain, unlike people such as Korngold or Herrmann, few set pieces. One cannot easily assemble excerpts, as wedded to the drama as they are. Webb mastered the art of creating the necessary atmosphere without, during the viewing of the film, making you aware of the music as such. Furthermore, fire destroyed almost all his scores in 1960. It so disheartened him that in the two decades remaining to him, he never wrote another.

It's practically a cliché among writers on film music that Webb's best scores accompanied the horror movies produced by Val Lewton. I don't quite agree. Certainly the Lewton scores are superior, but what about the noir scores like Out of the Past, Notorious, Crossfire, Mr. Lucky, or The Spiral Staircase. There are just too many distinguished scores in many genres (the comedy Bringing up Baby, the weepie I Remember Mama, for example) to spotlight a particular genre or producer. Webb was an all-rounder.

Nevertheless, it's nice to group, and the Lewton films, among the best and most intelligent in the horror genre (the horror usually takes place in the psyche, rather than from monsters; being human can be monstrous enough), make for a good group. We get more of Webb's Cat People score than of anything else. Webb makes good use of an idée fixe, the French nursery song "Do, do, l'enfant do." In the movie, it's usually anything but innocent, even creepy, and comes to represent the evil mystery of the cat people.

Despite a mess of a plot – a mish-mash of Jane Eyre, Rebecca, and stories of witches' covens – The Seventh Victim actually sneaks in a hard look at the nature of evil, even its banality, to borrow a later phrase from Hannah Arendt. A woman falls in with a group of Satanists, in the course of which she kills (against the club rules, by the way). Because she has told an outsider of her affiliation, the Satanists try her and condemn her to death. They will not kill her themselves: their verdict commands her to take her own life. Which she does. The movie does a great job of investing all kinds of terror in the gathering, only to have them deflated as a bunch of deluded losers. It hints at all sorts of things which Lewton snuck past the censors, including sexual frigidity and cruelty, and a bit of anti-clericalism. The music is Tchaikovsky-neurotic, but not over-the-top.

The costume drama Bedlam concerns the old English madhouse. Again, the monsters live in the mind, rather than in the cave, and it's not necessarily the people inside who should be restrained, but their minders. The score is to a great extent a decent example of phony Baroque, but Webb can come up with the modern goods at the scary moments. The Body Snatcher, another period piece, tells, among other things, an historical truth. Since doctors were prevented from dissecting human corpses (an old legal taboo dating back to at least Galen), they depended on "resurrection men" to (supposedly) illegally dig up recent graves and supply them with bodies for anatomical study. Sometimes the resurrection men didn't bother to dig anybody up. Murder was easier, and the product fresher. Boris Karloff plays the graverobber, one of his best performances, and Henry Daniell a doctor who happens to turn out more evil than his henchman. Since the action takes place in Edinburgh, Webb inserts hints of Scottish folk music into the score. Indeed, a plot point turns on a folk song (at least, according to my poor memory, it does). A blind girl makes her living by singing in the streets. On a black night, she is stalked by the body snatcher. She disappears into a dark passageway, and her singing abruptly stops – one of the great instances of film music silence.

I have never really "gotten" I Walked with a Zombie, and I suspect strongly that the fault lies in me. A nurse goes to the West Indies to care for a woman in a catatonic state due, apparently, to a spinal injury. After medical treatment fails, the nurse wonders whether voodoo can cure her patient. The movie is strong on creepy atmosphere, I admit, but the plot has never made much sense to me. Even the end offers no real closing of large narrative holes. However, Webb's score weaves a spell. With simple textures, he manages to suggest the motion of the Caribbean Sea, the stars at night, and the primitive mystery of voodoo, almost all with an effective, elegant employment of the vibraphone. Perhaps the most startling moment in the score is a voodoo chant for bass singers unaccompanied.

John Morgan has done his usual heroic job of reconstructing these scores. Stromberg and the Slovak Radio Symphony play okay, but those who expect Charles Gerhardt and the National Philharmonic as well as the glorious recorded sound shouldn't. The performances and recording are serviceable.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz