The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Stockhausen Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

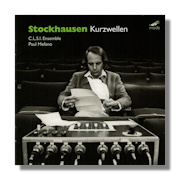

Karlheinz Stockhausen

Kurzwellen

- Jacqueline Mefano, piano

- Lissa Meridan, shortwave radio, filtering & ring modulation

- Michael Kinney, synthesizer & live electronics

- Martin Phelps, shortwave radio & live electronics

- Olga Krashenko, viola

- Gerard Pape, shortwave radio, filtering & ring modulation

- Stefan Tiedje, Tibetan bowls & live electronics

- Rodolphe Bourotte, shortwave radio & live electronic

Circle for the Liberation of Sound & Image

Mode 302

Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) wrote a number of works in the 1960s and 70s which have – rightly or wrongly – acquired something of a reputation for excess. Whether you regard them as eccentric (and perhaps puzzling), or as legitimate musical exploration and experimentation is likely to depend on your definition of music more generally. Kurzwellen (Shortwaves) was the first of a series of six works from the period to use the radio and what was received on it during performance and/or recording. It was an instrument in its own right. Kurzwellen dates from 1968 and is for six "players", or performers with short-wave receivers.

Those who are not closed to experimentation and wider horizons will accept the soundscape created in Kurzwellen as a worthwhile suggestion that some sounds around us – especially as they are produced with purpose and sequence by those responsible for the broadcasts – can at the very least make us think about sound. Perhaps they will remember the ways familiar to John Cage working a decade or two earlier. The very act of sifting and making sense of what we hear might be thought of as analogous or parallel to those cognitive and emotional processes with which we respond to (more familiar) music. We recognize, categorize, like, dislike what we hear; we wish for more of it; we see resemblances between sound(s). We accommodate and place phrases and extracts: most of Kurzwellen is starkly disjunct. They remain in our "mind's ear". Textures and combinations of sound as it is heard to progress across the airwaves and through the accompanying electronics and acoustic instruments (piano, viola, percussion) can be argued to share comparable characteristics with conventionally-notated scores.

By the same token, Stockhausen sought consciously and passionately to erase everything which could be considered as familiar from such compositions. Is that not something which composers have aimed for since (Western) music first evolved: thesis-antithesis (to create synthesis)? Analogously, given that we are nevertheless surrounded by sound, isn't it valid to ask the listener to hear both familiar and unfamiliar sounds in new ways as the composer and listener adjust expectations in the light of the feasibility of such an aim? One of the successes of Kurzwellen is that is is anything but a random collection of sounds.

Waves do ebb and flow. There is a logic; several (competing) logics perhaps. The tapestry which these sounds create is itself surely artistically valid. Stockhausen also instructs performers that unmodulated radio "artifacts" are to be avoided. It quickly becomes obvious that the composition is "managed", carefully and thoughtfully curated, and is much more full of clear and clean intentions than the casual, or antagonistic, listener may at first (be willing to) realize. Interactivity among performers, and between performers and listeners is at a premium.

Equally justified is Stockhausen's belief that to tap, and tap into, any underlying, universal (characteristics of) music which extend beyond (and so illuminate) one genre, style or motivation is a worthy enterprise. That may be seen in Kurzwellen's case as the outcome of a series of insights, glimpses, slices into wider wholes: the snatches of speech and melody from a culture with which we are perhaps unfamiliar connects us to it by virtue of the very fact that it is heard, picked up – and, ideally, is accepted – in such a wider context as offered by the piece (which lasts just over 45 minutes). Equally communicative is surely the whimsy. Perhaps even the provocation; for in the late 1960s the BBC famously felt itself unable to mount Kurzwellen around the time of its appearance for fear of infringing the copyright of anything originating from third parties over the air. Stockhausen's idea was not the first, either: Cage's own composition from a generation earlier Credo in US (1942) was the first of several to include a performer with gramophone and/or radio(s).

It's important to note that Stockhausen deliberately chose the particular sonic color of short-waves, rather than a collage of FM, or even digital, sources. That rather distant, perhaps eerie, interference-laden, clipped, compressed, and at times indistinct, fading sound suggests effort and perhaps even a slight wonder that transmission and reception ever work at all. This, of course, is integral to the composer's management of his sounds. By its very nature, short-wave in the 1960s was able to bring in signals from far more countries (and cultures, and in languages, and with purposes) than anything else available until geo-stationary satellites. This alone, if you stop to think about it, potentially creates a remarkably rich array of sounds, music, voices, and auditory impressions all simultaneously.

Tangentially, this furthers Stockhausen's ambition of creating Weltmusik, which would unite humanity by eliminating the impediment of being able to conceive and produce music only in one place (or at best, only one locality). Even cursory attention paid to Kurzwellen suggests implicitly that sound impinges temporally as well as geographically– Morse code (a Nineteenth Century invention) shakes hands with synthesized sounds, for example; New York and Peking – two very different capitals half a century ago – are heard together.

These performers, The C.L.S.I (Circle for the Liberation of Sound and Image) Ensemble do a magnificent job. They understand Stockhausen, his purposes and the best way to carry them out. C.L.S.I. was founded in 2007 by Gerard Pape and consisted of eight performers with instruments and laptops playing live. Their version – as heard on this CD – dates from one premiered in August 2011 at the annual "Stockhausen Sommer Course" in Kürten. It can – and, it may be argued, should – be easily accepted that computers and now much more advanced electronics take the place of the synthesizers of the 1960s. Even that change fits nicely into the "lessons" of Kurzwellen in the same way as do those realizations about the state of the world, temporality, space and the nature of sound and music. Resources change just as do technical progress with conventional instruments. The highly informative and helpful essay that comes with the CD alludes to the inclusion of a conductor (Paul Méfano) to offset the apparent "intransigence" of Pape. Like Stockhausen, the emphatic unification of sound, performer, conductor, recording engineer – and open-minded listener – into one borderless medium has to be understood for it to be properly appreciated. Here you have everything you need to reach that understanding. If you take nothing else away from this CD, to think – perhaps for the first time – whether other music cannot perhaps also behave this way would be productive.

The Ensemble fully respects the requirement of Kurzwellen for each interpreter to imitate, reflect and/or otherwise relate to a short wave event. And transform it meaningfully using the mature musicality of variances in duration, pitch, volume. Such changes are indicated for the most part by plus, minus or equals signs to indicate the relative changes from what went immediately before. At the same time, they acknowledge and capitalize on Stockhausen's conception by the time of Kurzwellen that it was more of a guided improvisation than a completely scored piece.This has the advantage, of course, for the generations of listeners who may come to this CD wanting (even if subconsciously) a performance which essentially lacks much that tethers it – perhaps inevitably – to the 1960s. One can't help but feel that those ahistoricist tendencies of the composer would have approved of this.

Even if you're looking for some of the more melodic and tonally familiar examples of contemporary musical thought, please give this a try. All plaudits should go to Mode for their dedication to new music… it's expertly produced, engineered and presented as it usual with Mode. This is the only recording of this pivotal work from the avant-garde of twentieth century music in the current catalog. It has much to say if given a chance. At the very least it helps build a picture of (this phase of) Stockhausen's musical thought. The production is excellent, everything one would expect from a version from half a century on. It's organic, persuasive, gently provocative in the ways in which it should be. Yet compelling, stimulating and – ultimately – eminently satisfying.

Copyright © 2018, Mark Sealey