The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Bloch Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

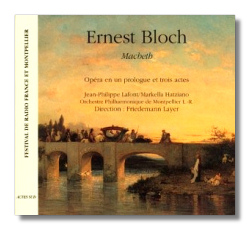

Ernest Bloch

Macbeth

- Jean-Philippe Lafont (Macbeth)

- Markella Hatziano (Lady Macbeth)

- Jean-Philippe Marlière (Macduff)

- Jacque Trussel (Banquo)

- Marcel Vanaud (porter)

- Sophie Fournier (1st witch)

- Hanna Schaer (2nd witch)

- Ariane Stamboulidès (3rd witch)

Orchestre Philharmonique de Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon/Fredemann Layer

Musicales Actes Sud OMA34100 2CDs 73:39 + 68:43

Summary for the Busy Executive: At long last. The first complete recording of a first-rank opera.

Bloch's music is nothing if not dramatic. However, a dramatic composer doesn't necessarily make an opera composer, as the work of Brahms shows. Bloch wrote his only opera, Macbeth, early on in his career. From the first, it's been a cult taste. The play – the shortest mature tragedy Shakespeare wrote – is ideally suited for opera: spectacle, witches, murder, madness, struggles for power, and a swiftness in the movement of events. Bloch's setting has always had a cadre of distinguished admirers. Winton Dean liked it. Andrew Porter thought it the best opera based on a Shakespearean tragedy (and I don't think he forgot Otello). It comes over as a weird cross between Boris Godunov and Tristan – Mussorgskian drama mixed with Wagnerian leitmotiv – but it works. That is, you don't think of leitmotiv or Mussorgsky while you listen. Nevertheless, the opera's original production in Paris flopped, due to rivalries within the cast, according to the sources I've read. Apparently, the production experience so turned off Bloch that he and his librettist, Edmond Fleg, scrapped plans for a King Lear.

It turns out we very likely lost a masterpiece. Fleg's libretto for Macbeth, despite some odd rearrangements of Shakespeare's sequence of scenes, nevertheless manages to keep a surprising amount of Shakespearean turns of thought and word-play, usually without literal translation. He suggests the oddity (to the French) of Shakespeare's language without breaking idiomatic French. One example will make the point:

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand? Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain? I see thee yet, in form as palpable

As this which now I draw.

Thou marshall'st me the way that I was going,

And such an instrument I was to use.

Mine eyes are made the fools o' th' other senses,

Or else worth all the rest.

Est-ce un poignard que je vois devant moi? La poignée tendue vers ma main? Viens! Que je te saisisse! Je ne puis te saisir, et pourtant, je te vois encore aussi net et palpable que celui-ci que je tire de sa gaine! Tu marches devant moi! Tu m'entraînes là où je vais! Non, c'est la fièvre qui a fait de mes yeux les fous des autres sens!

He moves things along even more swiftly than the original play by cutting down Shakespeare's five acts to three. He has edited brilliantly, losing nothing essential. For example, the early scene with Duncan, Malcolm, and the wounded messenger disappears, since much the same information arrives in a subsequent scene with Ross, Angus, Banquo, and Macbeth. Characters like Fleance never make it to the stage. More important, he also keeps Shakespeare's nightmare near-nihilism. The witches turn out to be much less frightening than Macbeth and his lady and the terror they unleash.

The main rap – if you can call it that – against Bloch's music is that it's a bit early, before the first "maturity" of the Jewish cycle, those works crowned by Schelomo. However, in my opinion, we're talking "relative" here. The opera all on its own grabs a listener, thrills to the bone, and conveys an almost philosophical depth. Immature Bloch turns out to yield nothing to mature almost anybody else.

Bloch invests the story with music of tremendous power. There's an extensive argument of leitmotiv, so extensive in fact that Bloch urged his publisher to print a list of them as preface to the score. It didn't happen. Now, a lot of operas use the Wagnerian innovation – not so much the assignment of an identifying "tag" to a character or an idea (which, after all, is at least as old as Mozart), but the carrying out of a "shadow drama" in the orchestra, commenting on the stage action. Bloch, however, seems to be one of the few composers to have noticed that Wagner's little tags – as in the astonishing prelude to Das Rheingold – have the ability to segue or even morph into one another. Bloch not only carries this out in Macbeth, he does so without resorting to Wagner's idiom. The language reminds me most of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov, perhaps because I've been listening to the Christoff-Cluytens recording recently, but even here Bloch differs in that he offers fewer self-contained set-pieces. He weaves a continuous fabric (in the case of the first act, roughly an hour long) in which characters break through to song-like moments, without ever singing an actual song. However, the music, vivid and memorable, grips you from the get-go. I don't miss an aria, because the music gives me as much drama as the play.

To some extent, the seamlessness of the opera has worked against its reception. You can't have an album of aria highlights or orchestral "bleeding chunks." Bloch attempted to provide the latter with a separate publications of two orchestral interludes, probably the only music from the opera that a listener has heard before. I first encountered a Swiss recording of these in the Seventies, and I reviewed an AS&V disc (CDDCA1019) earlier this year. As powerful as these chunks are and as sharply as they whetted my appetite to hear the opera whole, they become even stronger in their proper dramatic context.

The weakest part of the opera, in my opinion, is the death of Macbeth at the hands of Macduff, which comes and goes in an instant and with no time for the death to register. We see Macbeth in full battle fury, blink our eyes, and then listen to the celebratory fanfares at the tyrant's death. However, the play shows the same flaw. High points of an opera filled with high points include not one, but two mad scenes – one for Lady Macbeth and one for Macbeth himself, the latter very much indebted to the mad scene in Boris. Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinaine in a choral sequence that marches inexorably. Even more impressive are the builds toward and the ends of the first two acts. Bloch does a masterful job of keeping the lid on, letting out a little tension at key points, and allowing pressure to rebuild, so that when the climax comes, it is both overwhelming and justified, in proportion to the accumulated intensity. Furthermore, the climax corresponds to the end of the acts – a wise theater move in terms of audience psychology. Thus, the climax of the first act is not the death of Duncan, but the confusion among Macbeth's guests after the discovery. The end of the second act is Macbeth's mad scene, as he works himself into a bloody rage, unleashing a terror on the entire country.

The libretto emphasizes Macbeth and his wife and Macbeth vs. the witches. Macduff and Malcolm are ruthlessly cut to the status of Lennox and Ross in the original play. We get not Shakespeare's blood feud, but the sinner tempted and betrayed to hell. Thus, much depends on the two principal singers. Lafont as Macbeth and Hatziano as his lady are wonderful vocal actors, with a wide range of expression and great subtlety. These performances practically define nuance without sacrificing power. The orchestra, led by Fredemann Layer, gets through Bloch's complex score with narrative zest. It's a live performance, however, and not as polished as a studio recording would be. Nevertheless, Layer shows the stature of the opera. It's not merely worth the occasional revival; it should be part of the active repertory of every major opera house. I won't hold my breath. The choral work suffers most from mushy diction, but fortunately the sentiments the chorus expresses mainly echo the soloists. The libretto and the notes are entirely in French. Still, this album will likely end up one of my year's best.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz