The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schubert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

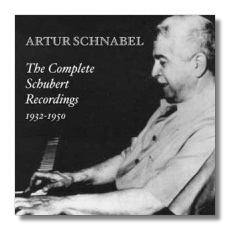

Franz Schubert

The Complete Recordings 1932-1950

- Impromptu D. 899

- Impromptu D. 935

- Piano Sonata #18 in D Major, D. 850

- Piano Sonata #21 in A Major, D. 959

- Piano Sonata #22 in B Flat Major, D. 960

- Moments musicaux, D. 780

- Piano Quintet in A Major, D. 667 "Trout"

- Divertissement à la Hongroise in G minor, D. 818

- Marches, D. 606

- Marches in G minor and B minor, D. 819#2 and 3

- Marches militaires, D. 733

- Allegretto in c minor, D. 915

- Andantino varié in B minor, D. 823

- Allegro in A minor, D. 947 "Lebensstürme"

- Rondo in A Major, D. 951

- Lieder (7)

Artur Schnabel, piano

Therese Behr-Schnabel, alto

Karl Ulrich Schnabel, piano

Claude Hobday, double bass

Members of the Pro Arte Quartet

Music & Arts CD-1175(5) AAD mono 5CDs: 65:10, 62:19, 71:42, 71:30, 74:29

This set handily collects every single studio recording that Artur Schnabel (1882-1951) completed of Schubert's music. (He recorded a set of the four D. 899 impromptus in 1942, but never approved it for release.) The earliest of these recordings date from 1932, when he and his wife Therese recorded seven Lieder on November 16, and the latest date from June 1950, when he recorded the D. 899 and D. 935 impromptus. All recordings were made in London, in EMI's Abbey Road Studios. Other labels (EMI Classics, Pro Arte, and probably others) already have reissued these recordings on CD, but many have gone out of print again, and Music & Arts's compilation is well done and economical: the five CDs are priced as four. Furthermore, these are new "state-of-the-art restorations" by Mark Obert-Thorn.

The quality of the sound is necessarily variable – a function of the materials available at the time of the original recordings. The D-major and B flat-major sonatas, and especially the Allegretto and the E-major March, all recorded in 1939, were released on poor quality shellac, and the steady roar and hiss of surface noise would be distracting, were the musicianship not so interesting. The rest of the recordings are better. The eight impromptus were recorded on tape, although that in itself is no guarantee of good sound, given the infancy that technology. All that matters is that the pianism comes through as best as it can, given the limitations of the time and place.

Many people associate Schnabel's recordings with technical fallibility, but it would be much more accurate to associate the pianist with risk-taking at the service of the composer. Very few pianists, for example, have had the nerve to play Beethoven's "Hammerklavier" Sonata at the metronome marking given in the score. Schnabel did so, and he "paid" for it, and he was no less reticent to "pay" for the demands he believed that Schubert had made in his scores. There are wrong notes in these recordings, and sloppy fingerwork, and wayward rhythms, but in the long run, they don't matter very much. Schnabel famously spoke of pieces which were "better than they can be played," and also said, "To try to serve music successfully with the fingers is quite hopeless. Music does not care for fingers." If the choice is between bland perfection and heartfelt musicianship, warts and all, I'd almost always take the latter.

Schnabel, who taught several great pianists to come, and who influenced so many more, espoused adherence to the printed score, but if he thought he could better realize the composer's intentions – particularly in terms of structure – by subtly modifying (should one say "distorting"?) rhythms, he would do it. Compared to his contemporaries, however, he was a saint, and what he did for Schubert's music cannot be underestimated. In the early part of the century, Schubert's sonatas were not given the respect and attention that they receive today. Pianists would play an impromptu here and there, and maybe a Moment musical or an arrangement for piano two hands of a Marche militaire, but they and their audiences were largely in the dark about what Schubert had to offer. Schnabel, and the recordings that he made, changed all that.

A few words should be said about Schnabel's collaborators. By 1932, Therese Behr-Schnabel was a vocally characterful singer rather than an alluring one. The seven Lieder presented here will win no one's kudos for beauty of tone, yet there's undeniable interpretive power to underlie the astringency of her vocal delivery. Karl Ulrich Schnabel, Artur's son, was a fine pianist himself, and the more than 85 minutes of music for piano four hands are as excellent as everything else in this set. (We don't know – and can't tell – which parts were taken by the father, and which were taken by the son.) The "Trout" has been a classic since its release, thanks to the lean ebullience of three-quarters of the Pro Arte Quartet (Alphonse Onnou, Germain Prévost, and Robert Maas) and also double bassist Claude Hobday.

The 24-page booklet contains essays by Mark Obert-Thorn (on the original recordings themselves) and Harris Goldsmith (on the music and the pianist). These will be very helpful both for the seasoned collector and for someone who is just beginning to look into who Schnabel was, and what his Schubert was all about.

Copyright © 2006, Raymond Tuttle