The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

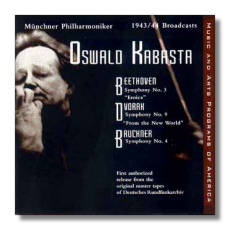

Oswald Kabasta

1943/44 Broadcasts

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony #3 "Eroica"

- Antonín Dvořák: Symphony #9 "From the New World"

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony #4 "Romantic"

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra/Oswald Kabasta

Music & Arts CD1072 ADD? 2 CDs: 72:20, 70:29

Many a talented classical musician's reputation has blossomed from being "on the right side," politically speaking. Conductor Oswald Kabasta's story is a sad example of what can happen when a musician ends up on the wrong side, either through choice or circumstances. In the 1930s, Kabasta joined the Nazi party, and the Munich Philharmonic became known as "The Orchestra of the Capital of the Political Movement." (Music & Arts reproduces the orchestra's banner in the booklet to this set; the Eagle and the Swastika both figure prominently.) Kabasta started signing his official letters with the words "Heil Hitler." As went the Third Reich, so went his fortunes. He remained a respected and successful figure in German musical life throughout the 1930s and into the early 40s, and an advocate for the works of composers not necessarily sanctioned by the government. Then, difficulties with the Philharmonic's management, and an Allied bombing of its performance space, took a toll on Kabasta's physical and emotional health, and he was forced to step down for a period of recuperation. By the time he had recovered, the war was over, the Allies were in control, and Kabasta tried to return to his orchestra. It was not to be. The occupation government was unsympathetic to Kabasta and his Nazi affiliation, and he was barred from pursuing a musical career in the fall of 1945; Hans Rosbaud was installed instead. In despair, Kabasta self-administered a lethal dose of the anesthetic Veronal on February 6, 1946. Although Munich continued to honor its former Generalmusikdirektor, Kabasta was quickly forgotten by most of the world. There is little doubt that his Nazi ties scuttled his career while he was alive and sullied his reputation after his death.

Now, more than fifty years later, it is possible to be more dispassionate about Kabasta's life and talents. Collaboration between Music & Arts and the German Radio Archive (Deutsche Rundfunkarchiv, or DRA) has resulted in releases of broadcast performances conducted by Richard Strauss, Hermann Abendroth, and Hans Rosbaud, as well as by Kabasta. On the present two-CD release, Music & Arts offers a Beethoven "Eroica" from 6/19/43, a Dvořák "New World" from 7/14/44, and a Bruckner "Romantic" from 6/30/43. (The "New World" is split across the two discs, unfortunately.) The sound quality is very good, and indeed, many commercial discs of the era do not hold up so well.

The "New World" recording has an interesting history. After the war, many German radio tapes were purchased by budget classical labels. Records often were released without proper credit to the performers, particularly at the start of the LP era. Kabasta's "New World" was identified as the work of the "Berlin Symphony conducted by Karl List" and then as that of the "National Opera Orchestra." Then claims were made that it was a 1941 recording made by Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, causing Furtwängler's disciples to become ecstatic. It wasn't until the 1990s and detective work by German discophiles that the truth came out. It certainly doesn't diminish the quality of this performance to know that Furtwängler didn't conduct it. This is one of the most exciting "New World"s I've ever heard. Tempos are driven and rhythms are sprung in a manner that might not have pleased the composer (even the Trio of the Scherzo is a gallop), yet there's something fascinating about the insistence of Kabasta's approach. It's surprising how well the Munich Philharmonic keeps up with him.

Beethoven and Bruckner were Kabasta's meat and potatoes. Both the "Eroica" and the "Romantic" feature brisk tempos, but they are not as violent as the Dvořák. Nevertheless, Kabasta's "Eroica" can best be described as militant, and no one can say that the conductor was emotionally detached from the world events that surrounded him. The "Romantic" is remarkable for the flexibility that Kabasta builds into his brisk tempos; his Bruckner breathes. While Kabasta essentially uses the Haas "critical edition" of 1936 in this performance, he feels free to go back to the earliest (and sometimes corrupt) first published editions when it suits him to do so. Whatever he conducted, Kabasta seemed concerned with driving the music forward – but not inexorably – and with obtaining the greatest clarity of textures. The weight came from accents and the interpretation's fire, not from thick orchestral playing or slow tempos.

In short, this is a fascinating issue, and one well worth exploring for anyone who admires Furtwängler's athleticism. A handful of Kabasta's Electrola studio recordings are available on the Preiser CD label, and these can also be recommended as complements to the present collection.

Copyright © 2001, Raymond Tuttle