The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bantock Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

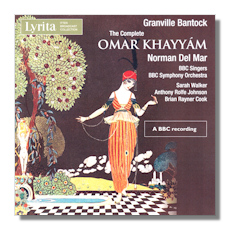

Granville Bantock

- Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám (1906-1909) 1

- Fifine at the Fair (1912) 3

- Sappho for Mezzo-Soprano & Orchestra (1906), abridged 2,3

- The Pierrot of the Minute (1908) 3

1 Sarah Walker, mezzo-soprano

1 Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor

1 Brian Rayner Cook, baritone

2 Johanna Peters, contralto

1 BBC Singers

1 BBC Symphony Orchestra/Norman del Mar

3 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Norman del Mar

Lyrita REAM2128 ADD *Stereo/Mono 4CDs

Granville Bantock (1868-1946) was one of the generation of British composers who built the "English" school of music in the first half of the twentieth century. It sounds as though its defining characteristic ought to be romanticism – nationalism even; but in fact such music from the period embraces much more. Parry, Stanford, Delius, Holst, Bridge, Ireland, Bax, Rubbra, Finzi and Walton and of course Elgar and Vaughan Williams should be cited as superb creators of large-scale lush orchestral writing influenced by the German Romantics of the nineteenth century. While Warlock, Grainger and Quilter worked along parallel lines on a smaller scale.

But listen dispassionately and music of a broader appeal is revealed. Although, like Wagner, Mahler, and in different ways Strauss and Bruckner, the canvas of Bantock's vision was extensive, it was rarely self-consciously ambitious or far-reaching for its own sake. One of the most attractive features of this rather special set of four CDs is what, for some, may be a revelation of some of the ways in which music was made a generation or two ago – so as a historical document. The main work is a setting in its the entirety (all 101 quatrains) of Edward Fitzgerald's (1809-1883) epic, the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyám".

The music is varied; it ranges from focused monolog and tight dialog to expansive, open choral and full orchestral passages, which flow into one another naturally and in a way that is wholly consistent with the substance of Fitzgerald's translation of the musings on philosophy, science, poetry – and life by the Persian poet Omar Khayyám (1048-1131). Bantock's use of tonality and orchestration make the long poem accessible and closer in feeling (while certainly different in spirit from its mediaeval origins) to the time in which it was written. Yet things never drift or draw attention to the length of the undertaking.

Two aspects of the original do strike the listener new to Bantock's work though: its lyricism; and that composer's self-confidence. Bantock is an expert lyricist. He worked on the composition while he was still relatively young. An interpretation which really gets inside the work needs to understand the world of Omar Khayyám, of Fitzgerald and how Bantock chose to construct this large choral work from the relationship between the two.

That this performance works so well is in no small part due to the superb expertise of the ebullient, energetic conductor, Norman Del Mar. Like his contemporary, Adrian Boult, Del Mar was a vigorous promoter of new music as well as the British repertoire during his long association with the BBC; in the Rubaiyat he conducts arguably the finest of its several orchestras, the BBC Symphony Orchestra (and Singers), in a recording with equally distinguished soloists from March 1979 on the occasion of the first complete broadcast.

For all its conception in the grand tradition of large-scale choral music on substantial texts in philosophical veins, the work is notable for combining the secular, the Middle Eastern and the avowedly modern (in its time). One might think of the secular oratorios of Handel for a more familiar analog. In its refusal to capitulate to lushness and overwhelming emotion, the fact that Bantock's musical activities extended to contributions to the "Dictionary of Modern Music and Musicians" and espousal of Prokoviev and Sibelius and other modernists goes some way towards explaining the composer's place amongst musicians of his era. Indeed, Henry Wood said of Bantock, "[he was]… a man of expansive mind… His outlook is big and noble…" And that's exactly the kind of music to be heard here. For every way in which it is generous and large in scale, it's focused, specific and (if not compressed) always leading somewhere.

The end of CD Three and all of CD Four are taken up with equally enthralling pieces also by Bantock, all composed at around the same time as he was working on the Rubaiyat: Fifine at the Fair dates from 1912 and reveals Bantock's gift of orchestral color well. Again, Del Mar pulls out the subtleties and strengths of delicacy and confidence. That he was a Strauss aficionado is evident from the way the strings of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra (of which he was Chief Conductor from 1960 to 1965) lavish such care on the more reflective passages – such as those towards the beginning of Fifine [CD 3 tr.6].

Of the nine "fragments" for mezzo-soprano and orchestra that make up Sappho from 1906 numbers I to III, V, VI and IX are presented here. Contralto Johanna Peters sings judiciously and with a dignity redolent of Ferrier and her generation. But her delivery and the way she infuses the music with meaning lack no clarity. She persuasively reminds us poignantly both of the epic choral work we have (probably) just enjoyed and – with the ebullience of Del Mar's strong guidance – and of just how adept Bantock was at eliciting color and light from voice and instrument. Combinations, textures, implied forces and emotions slip easily into view, do what they have to do, and slide away knowing that they have made their impression on the listener. The Pierrot of the Minute (1908) is a lighter overture dedicated to Otto Kling, a close collaborator of Bantock's at Breitkopf and Härtel.

With Del Mar, something is always about to happen in the music; one awaits what's next with eagerness – and is never let down. His conception of these key works by Bantock is also one in which all the performers seem to be using instinct as well as superb technique to work in close step with one another towards an unquestioned goal – that of presenting the music in the brightest light possible. In some ways, this results in accounts that might seem less reflective than their equivalents from today might, marginally less questioning. In reality, the excitement, sense of direction yet the absorption in pure sound (always hallmarks of Del Mar's conducting) soon become utterly natural and compelling. There are moments (three minutes from the end of Fifine[CD.3 tr.6], for instance) when significant dynamic contrasts do seem a little more pronounced than if conceived and recorded these days. The players just "jump in" and play. But the contrast is more striking than off-putting.

The acoustic on these four CDs is perhaps a little better than might be expected, given the recordings' ages (37 and 48 years). The recordings of the shorter pieces are ten years older than those of the Rubaiyat; the differences in breadth and clarity are noticeable. They are monophonic too. While not being in any way 'boxy', the latter are certainly less spacious. Yet clarity, precision and presence are not lacking in any way. The relative dynamics of vocal and instrumental soloists, ensembles and orchestral tutti add color and depth in the most natural of ways. Del Mar and the engineers of the time captured the performance in the style current a couple of generations ago… the most important entity was the music, its performers were assembled, their technique and ability to articulate the essence of the composer's intention was taken for granted – and rightly so. It was assumed by the BBC that the audience was receptive and knowledgeable and the result was calm, uncluttered and winningly effective in every way. And that is what we have here on a CD set that may start as a document; but will also satisfy for the music in its own right.

The 24-page booklet that comes with the CDs is exceptionally good on the compositional and performance history of these works. They were all very much of their time and intimately bound in the way music-making worked in Britain during Bantock's maturity and after his death. This makes for fascinating reading for those interested in a world which has been lost almost entirely. Then there was greater acceptance of serious music, fervent patronage and dedication to its promulgation. The booklet has the full texts in English, an introduction to Bantock, his approach to the poem, and of special interest a lengthy discussion of the role of Michael Pope at the BBC, who acted as a champion for Bantock and the "Rubaiyat" in particular. Part I was actually performed under the auspices of the BBC with Sir Thomas Beecham as early as 1929. Although it's the music that matters, to see how differently things worked then is always interesting. Walker, Rolfe Johnson and Cook are completely at home in what is a demanding work. They match clean, penetrating enunciation with illuminating (yet not at all spuriously rhetorical) insight into the substance of the poem.

Yes, there are other recordings of Fifine, Sappho and The Pierrot of the Minute. Vernon Handley recorded the Rubaiyat with Catherine Wyn-Rogers, Toby Spence, Roderick Williams and the same BBC Singers and Symphony Orchestra ten years ago (Chandos CHSA5051). And that's a fine account. But the present set from Lyrita has a valid appeal a long way beyond that of being a snapshot in time… what the BBC, once Britiain's most prominent and effective patron and sponsor of serious music was then capable of. The nuances, gentleness yet conviction by performers and conductor in what is always likely to be something of an eccentric composition on these three CDs (and the happily accessible works from an even earlier era) somehow show why. Recommended for the music in its own right as much as the historical insight.

Copyright © 2016, Mark Sealey