The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Eisler Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

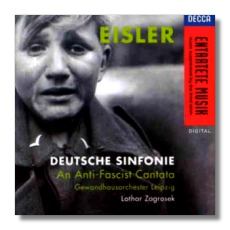

Hanns Eisler

Deutsche Sinfonie

An Anti-Fascist Cantata

Hendrikje Wangemann, soprano

Annette Markert, alto

Matthias Görne, baritone

Peter Lika, bass

Gert Gütschow & Volker Schwarz, speakers

Ernst Senff Chor Berlin

Gewandhaus Orchestra Leipzig/Lothar Zagrosek

London 448389-2

At a time when major labels seem to be cutting back, let's congratulate London (British Decca) for its continued commitment to its "Entartete Musik" series, dedicated to the performance of works or composers suppressed or killed by the Third Reich. Not every CD has been a winner, due to weak repertoire (the historically important but musically negligible Krenek opera Jonny spielt auf; Krenek wrote far better than this) or weak performances (almost everything conducted by John Mauceri), but at least it hasn't been yet another release of Eine kleine Nachtmusik. At a time when music seems to be marketed to the upscale Pepsi generation as another prestige consumable, this series stands against the tide of the Dumbing Down.

Most know Eisler, if at all, as a composer of incidental music to Brecht plays. Of Brecht's three major musical collaborators – Kurt Weill, Eisler, and Paul Dessau – Eisler was probably the most politically and personally compatible with the playwright. His songs cut as sharp as Weill's, in my opinion, but the major part of his musical output remains mostly unknown. Therefore, I welcome this disc.

Politically, Eisler was a committed Communist, although he and Brecht broke with Moscow over the Stalin-Hitler non-aggression pact – with good reason, since the two of them were on the Gestapo hit list. Both wound up in Hollywood, where Brecht had a hard time making ends meet and Eisler supported himself writing scores to very forgettable pictures, usually costume epics like The Spanish Main. After the war, Eisler and Brecht were caught up in anti-Communist Congressional hearings, which so spooked them that they lit out for East Germany (Deutsche Demokratische Republik), where Brecht founded the Berlin Ensemble and Eisler wrote, among other things, the DDR national anthem.

As a Communist artist, Eisler dedicated himself to the enlightenment of the workers and found himself in some aesthetic difficulty. He was also a committed serialist, convinced that Schoenberg's methods represented the way upward and forward – Excelsior! The problem, which Eisler clearly recognized, was that most of the proletariat needing enlightenment wouldn't have touched Schoenberg's work with a barge pole. Why was Eisler so convinced? I believe aesthetic discussions of music from such German writers of the 1920s as Adorno and Benjamin influenced him. In an interesting (and rather loopy) essay, "Schoenberg vs. Stravinsky," Adorno (or was it Benjamin?) advanced the idea that Schoenberg's music, freeing the tone from the "tyranny" of the harmonic hierarchy, where one tone has greater weight than another, was "democratic," while the neoclassic Stravinsky was "monarchical." He therefore praised those composers deriving from Schoenberg (Berg, Webern, Weill, and Krenek after his conversion) and dumped on those who followed Stravinsky or Hindemith. After Schoenberg (who turns out to have been not so much democratic as papist) excommunicated Weill from modernism, Adorno dumped on the latter as well. The knots that these fellows twisted in their own brains amaze me. I'm an altogether simpler sort and agree with Ellington, whose music enlightened many more heroic proles than either Schoenberg or Eisler: "If it sounds good, it is good."

Still, the aesthetic impasse Eisler found himself in forced him to think about ways through. We find these in abundance in the Deutsche Sinfonie. First, he found rows that emphasized tonal relationships. Berg, of course, had pioneered this procedure in his Violin Concerto, which gives great rhetorical emphasis to the open strings of the violin and to triadic sequences of notes. Second, Eisler seems to have intuited that audiences could tolerate instrumental complexity better than vocal complexity. Therefore, in the vocal music, he very rarely transposes rows to other pitches (thus undermining a sense of pitch stability) and, when he does, the relationships between original and transposed rows are either up or down a fifth, analogous to the most common and simplest tonal modulations. Schoenberg also did this in his late period or, dividing the row in half, commenced the second set of six notes up or down a fifth. Finally, and I believe most important, Eisler's phrasing and formal structures avoid late nineteenth-century Wagnerian, "organic" paths. Not for him Wagner's "endless melody," with its elisions of cadential stops and continuations. Eisler uses definite stops at more or less predictable points. Eisler's melodies may sound strange, but I believe the listener at least accepts them as melodies, just as the listener would accept a melody by Weill.

To some extent, the Deutsche Sinfonie is mistitled, for it's more cantata/oratorio than symphony, despite some brief movements for instruments alone. Eisler fashioned a libretto from poems by his favorite Brecht and, in one section, by poet Ignazio Silone, a Communist who had also broken with Moscow, in this case over the issue of Stalin's "show trials." Eisler composed the work mainly in the 1930s and completed the final movement in the late 1950s. The work belongs, both musically and politically, to the Thirties – musically similar to the works of Toch and Weill's second symphony, despite the differences in technique, and full of political warning to the German people and to those Communists in lock-step with Moscow. Does the work rise above mere reportage and rather obvious agit-prop, as Weill's political operas do time and time again?

Unfortunately, I've phrased the question badly. The crimes reported here still occur. This is not a matter of "how things were then." We may better question whether the music makes us care. It does, but in fits and starts. To me the most successful sections – "To the fighters in the concentration camps (Passacaglia)," "Burial of the trouble-maker in a zinc coffin," and the remarkable "Peasant Cantata" – show a composer with a keen dramatic sense, appropriating in large part Mahler's grotesque musical imagery – for example, the military bugles and drums and symphonic funeral marches – just as Weill does in his Violin Concerto. Furthermore, each piece of the cantata shows a suave handling of large forces, finding novel combinations and effects, best heard in the "Dialogue in Whispers" melodrama from the "Peasant Cantata." One also senses great art in Eisler's marriage between new idiom and old forms, as in the "Passacaglia," where the composer works to have his row both produce variations and "come out right" over his passacaglia bass line, made up of parts of the row. The longest, most ambitious section of the work is the "Worker Cantata," to Brecht's "Song of the Class Enemy." Despite powerfmoments, I can't call it a success. The poem is long and strophic. Eisler varies his orchestration with great resource, but cannot overcome the feeling of sameness induced by a long strophic setting. Eisler follows Mahler's example here. But Mahler's strophic texts were much shorter, thus making it easier to shape the progress to an emotional arch, or he relied to a greater extent on the orchestra to build a symphonic movement. Eisler's setting – and a brisk, non-dawdling one at that – runs about fifteen minutes. Eisler jolts the listener, but doesn't manage to carry him along.

The performance is very, very good indeed. It's not a "star turn" by any means. Zagrosek and his players direct all their energies to illuminate the work. Singers' diction is crisp. The text is always intelligible, which would certainly have warmed the hearts of Eisler and Brecht. Even the chorus does more than just stand there and let fly. They sing dramatically and expressively. Zagrosek's grip on this very difficult music is firm, and – passing the highest test I know – makes it communicate directly to the listener. One can forget about tonal/atonal and just groove. Recorded sound is London's usual superb and balances – which must have given engineers fits, if we consider the large forces involved – are beautifully clear and, one might say, natural.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz