The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Cowell Reviews

Creston Reviews

Dello Joio Reviews

Turok Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

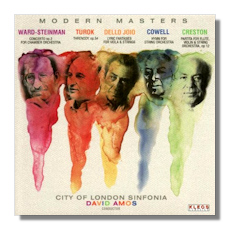

Modern Masters

American Music for Chamber Ensemble

- David Ward-Steinman: Concerto #2 for Chamber Orchestra

- Paul Turok: Threnody, Op. 54

- Norman Dello Joio: Lyric Fantasies for Viola & Strings

- Henry Cowell: Hymn for String Orchestra

- Paul Creston: Partita for Flute, Violin & String Orchestra, Op. 12

Karen Elaine, viola

Yossi Aranheim, flute

Nicholas Ward, violin

City of London Sinfonia/David Amos

Kleos KL5128 59:31

Formerly on Harmonia Mundi HMU906011: Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

A sampler of – I was about to say "conservative," but that's not right – rather, "idiosyncratic" American composers, both pre- and post-World War II. Almost all of them came to notice early on, although hardly any professional body programs them today, and I think every single piece on the CD strongly memorable. However, the official consensus of those who most strongly influence musical opinion probably disagrees with me. By definition, idiosyncratic runs counter to influential. None of these men has major disciples, as Schoenberg and Stravinsky surely do. I don't find the criterion of influence all that compelling, although I understand why music historians resort to it. To me, a composer is as good as the best music he writes.

Some of them – Creston and Dello Joio in particular – had the misfortune of conservative factions putting them up as the anti-Schoenberg. I say "misfortune," first because their music is not a manifesto, even though it exhibits a strong profile. To paraphrase Samuel Barber, mainly they do their thing. Second, the reaction against them I think mainly due to this inflation. Not only was their music plowed under, but it was done so with relish. Nevertheless, the king really did wear clothes. Nobody duped the audience, and amateurs and recordings have kept some of their scores alive. Cowell, eclipsed by both the dodecaphonists and the students of Nadia Boulanger, probably still attracts the highest regard.

A student of Wallingford Riegger and Darius Milhaud, among others, David Ward-Steinman's music stands out for its rhythmic vigor, effortless contrapuntal brilliance, and water-clear orchestration. The Concerto #2 for chamber ensemble blends the old-style concerto grosso with elements of the modern concerto, in that it spotlights instruments with virtuoso solos and gives memorable passages to contrasting instrument families. The composer calls it a revision of his Concerto #1. It has the traditional three movements: fast, slow, fast. The movements, modest in size and resources, nevertheless contain great depth and beauty, particularly the slow movement, as fine an American composition as any I know.

Paul Turok has flown so far under the radar, you won't find even a Wikipedia entry on him. I've heard only two works: this one (the first) and a fantastic set of orchestral variations on the 19th-century campaign song "Lincoln and Liberty." Turok's music pulls off the difficult: an outstandingly original, poetic voice in a conservative idiom. The Threnody is essentially a public song of lament, but Turok's lament sounds little like Vaughan Williams, Hindemith, Bartók, or Stravinsky – to name four composers who worked a nice line in that genre. Turok doesn't invent a new language as much as some new musical conventions that evoke sorrow, a new way to sing about grief.

Of all the composers here, Norman Dello Joio has probably fallen the furthest in critical appreciation. Once considered one of Hindemith's finest American pupils (sounding nothing like Hindemith), he now gets performed by amateurs, undoubtedly due to the heap of interesting works for non-pros, an area of endeavor inherited from his teacher. Like Hindemith as well, Dello Joio has a huge catalogue with a significant number of masterpieces awaiting the intrepid listener to discover them.

Aside from a handful of small early pieces, Dello Joio's music sounds nothing like Hindemith. His "typical" sound – that is, my mental image of his idiom – warm and lyrical, reminds me a little harmonically of pop music of the Forties. However, Dello Joio has a wide range of expression. The Lyric Fantasies for viola and strings surprise a listener used to the meme, in that they work a suaver, cooler vein. Indeed, here you can definitely hear the links to Hindemith, even though in general Dello Joio casts his own line. The score has two movements: a meditation, highly suited to the viola's sound; a finale that alternates between a spirited gigue and long, singing lines, both types of music superbly adapted to the viola's strengths. A gravely beautiful work.

I'd say the same of Henry Cowell's Hymn for String Orchestra. Cowell always went his own way – or, rather, any way he cared to go. His catalogue reveals so many different pioneering styles that I suspect this has worked against him. He refuses to make things easy for musicologists. The Hymn comes from one of his most gorgeous parts of his work – his take on Americana. Unlike the more prominent composers in this vein like Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson, Cowell went not so much to folk sources, but to the Early American "singing schools" and composers like William Billings and Justin Morgan for his inspiration. Outside of scholars, he was one of the first artists to study these works seriously. The originals have a home-grown, hand-made quality – the opposite of slick. They are mainly modal (at their most harmonically "advanced," they recall half-remembered scraps of Handel and Arne), and their counterpoint bare-bones basic. As Cowell noted, the two main genres were hymns and "fuguing tunes" (the title Cowell attached to a series of his own scores), more really like rounds than traditional fugues. This particular score of Cowell's stunned me, it was so strangely lyrical. For those of you interested in musical architecture, its form is both sui generis and thoroughly convincing.

Of all the items on this program, people might most likely recognize Paul Creston's Partita, thanks to Walter Hendl's classic recording, dating all the way back to the days of mono vinyl. Like Henry Cowell, Creston (born Giuseppe Guttoveggio; various accounts of the name change, including from the composer himself, contradict one another) largely taught himself, also forging an idiosyncratic, highly rhythmic style. Creston created himself as an artist in an almost Gatsby-like way. Cross-rhythms generating large spans of music particularly interested him. The Partita, like the Ward-Steinman Chamber Concerto, packs a lot in a little. It takes off in an obvious way from the Baroque concerto grosso. Filled with memorable tunes and toe-tapping beats, it also reworks themes and harmonic sequences in its various dances. If it were merely a lollipop, it is way better-written than it has to be.

David Amos hasn't had the career he should have. I don't know how good his Brahms would be, but then again I don't believe any composer or restricted group of composers should determine a conductor's worth. Amos has brought hundreds of worthy new works to light and strongly advocated for forgotten scores like these. A classic disc, should you ask me.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz