The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

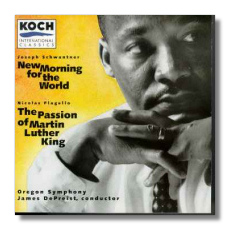

Schwantner & Flagello

Works in Honor of Martin Luther King

- Joseph Schwantner: New Morning for the World

- Nicolas Flagello: The Passion of Martin Luther King

Raymond Bazemore, narrator and bass

Portland Symphonic Choir, Oregon Symphony Orchestra/James DePreist

Koch International Classics 3-7293-2H1

I consider Martin Luther King the greatest public figure of my time, as well as its greatest public speaker. I heard him in person four times, none of them the occasion for a major speech, but still eloquent and, even more important, to the point. Further, he addressed three different kinds of audiences: academic, general, and "home church." Although the tone changed for each crowd, the basic rhetorical strategies did not. We tend to remember the perorations, the flights of Biblical rhetoric, but, as in Lincoln, there was always a solid argumentative foundation for them. This wasn't the babble of politicos – no "new morning for America," "thousand points of light," or "bridge to the 21st century" – meant to obscure and to confuse history, but the crown of a granite column of argument.

Not surprisingly, some composers have attempted, with varying success, to set the Hundred Great Moments. It would seem to be a natural: a great subject and grand words. However, most of the pieces so inspired have raised the old question: is it better to write a poor poem on man's place in the moral universe or a good poem about a jabberwocky? I plunk down on the side of the latter.

Schwantner has, of course, had a distinguished career, including a Pulitzer-Prize composition. Most of the time, I find his music rather bland, though expert, and one piece tends to blur into another. I'm reminded of John Candy's line in Splash: "Hey, when I find something that works, I stick with it." New Morning represents for me a glorious exception. Here, Schwantner forsakes his usual watercolor-and-pastel approach to explore a new, more vibrant idiom and comes up a winner. Copland's Lincoln Portrait obviously fathered the piece in the way it uses narrator, although Schwantner's powerful, thoroughly contemporary musical idiom itself owes nothing to Copland. In fact, in construction and, above all, in emotional effect, I think the work surpasses Copland's Lincoln. Among its beauties are an opening of bells and alarums and a hymn of great nobility, without calling to mind any composer other than Schwantner. The musical structure is important, since it's really analogous to King's logical structure. A long work of nothing but high points becomes rhetorical dross. Of course, one needs above all a good dramatic reader with at least musical instincts, if not actual musical skills. I remember hearing a performance with the great American baritone William Warfield and Dohnányi leading the Cleveland Orchestra. The Oregon Symphony under DePreist does very well, but Bazemore just about sinks this account. In fact, it sounds like he learned the piece phonetically. Still, this is the only available recorded performance of a major postwar American score. On that basis alone, it's worth your time. Just sit back with the text in front of you and try to imagine a better reader.

Flagello has been on the periphery of American music for a while. I first enountered his stuff in the 60s. The works I heard seemed to me to be less-than-memorable, but certainly attractive while they lasted. Unfortunately, The Passion of Martin Luther King is a windy bore. The model here is Vaughan Williams' Dona nobis pacem and Britten's War Requiem, with a mingling of traditional Latin and English texts. To give Flagello his due, you can see his attempt to relate these texts to King's words by juxtaposition. Unfortunately, the music just isn't very compelling and sounds like something Howard Hanson would have thrown away – there's a whiff of gentility here, without Hanson's considerably vital artistic individuality. If you heard 10 minutes of this score, I doubt anyone would guess the composer or would take the trouble to. Again, Bazemore is the weakest part of the performance – a wheezy voice, noticeably flat intonation, and just no juice. Furthermore, the score isn't strong enough on its own to sustain interest. I should in good conscience point out, however, that Jim Svejda likes it.

It's a tossup, folks.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz