The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Theodorakis Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Mikis Theodorakis

Canto General

Alexandra Papadjiakou, alto

Frangiskos Voutsinos, baritone

Berliner Instrumentalisten/Lukas Karytinos

Rundfunkchor Berlin/Sigurd Brauns

Intuition Records int31142

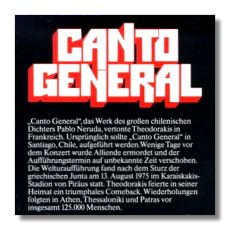

When I first heard Canto General over twenty years ago, I thought: this is music for revolutionaries to sing while storming the gates. Based on the greatest poem by the renowned Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, this oratorio is vibrant, dramatic, and unabashedly inspiring. My twenty years of listening to a squeaky cassette has not dimmed its power. Its melodic and emotive power is astounding. It ranks with Dmitri Shostakovich's Symphony #13 (Babi Yar) or his cantata, The Execution of Steka Razin. Yet as Shakespeare's Dogberry says, "comparisons are odorous." I should say I've really never heard anything like it and leave it at that.

Alexandra Papadjiakou's lusty alto voice sings the opening piece, Algunas Bestias, an exhultant aria about richly varied South American life. Using rousing choral accompaniment, bouzoukis, and tympanis, Theodorakis constructs an undulating panorama, varying volume and rhythms with ease. Suddenly he slows the tempo as Papadjiakou sings tenderly: "It was the night of the cayman,/the night pure and pullulating/with snouts emerging from the ooze…" Then the tempo picks up again, ending the piece with terrifying exclamations as an anaconda lunges from the water, "devouring and religious." Why hasn't anyone turned this into a ballet?

The centerpiece of Canto General is the stirring Los Liberatadores: "Here comes the tree, the tree whose roots are alive/it fed on martyrdom's nitrate/its roots consumed blood…." Papadjiakou sings these lively lines as if hurling thunderbolts.

Theodorakis continually alters the relationship between singer and chorus: sometimes Papadjiakou delivers her lines with droning choral accompaniment, other times she alternates with the chorus. These varied effects continually astonish. The Rundfunkchor Berlin does an excellent job, never overpowering either lead singer.

However, some pieces are not successful, despite Theodorakis' attempts to transcribe Neruda's more tendentious verses. Baritone Frangiskos Voutsinos sings Voy a Vivir, an andante aria about affirmation, amid swinging gallows in postwar Athens and murderous gangs in Franco Spain. Unfortunately, the music isn't up to its material. Its monotonous melody and solemn choral accompaniment impart a dreary hymn-like quality. A Mi Partido, Neruda's paean to his membership in the Communist Party falls flat, despite Voutsinos' earnest rendition. Lautaro almost takes off, but its trenchant lyricism is marred by inappropriate flute accompaniment and other failed musical elements. Sandino, virtually a recitative about the famous Nicaraguan rebel, is melodically uninventive and strays. Theodorakis' elegy Neruda Requiem Aeternam is mediocre because of its excessive adulation and – oddly enough – its piety.

Not all the arias are this political. Vienen los Pajaros is a jubilant, evocative piece about the many bird species circling the countryside. "All was flight in our land," sings the chorus, accompanied by spry celestas and folk guitars. At times the voices swoop around the harmony like condors. Once again, the light is on Papadjiakou whenever she opens her mouth, even when enveloped by the chorus.

Few can sing so melancholically about death and starvation as this woman, but she can also rise in full-throated anger at the ravages of injustice. Voutsinos is a competent baritone, but lacks the sardonic edge to his voice that these pieces can demand. Conductor Karytinos orchestrates the complex harmonies well, particularly in his sense of pacing. It would have been so easy to have made this work bombastic. Thumbs up to Allegro for importing this rare gem. (Note: Atmasphere engineered an atrocious recording in 1988, but the less said about that, the better.)

Copyright © 1998, Peter Bates