The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Concert Review

Concert Review

Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky

The Queen of Spades, Op. 68

- Misha Didyk (Hermann)

- Alexey Markov (Tomsky)

- Vladimir Stoyanov (Prince Yeletsky)

- Andrei Popov (Tchekalinsky)

- Andrii Goniukov (Surin)

- Mikhail Makarov (Tchaplitsky)

- Anatoli Sivko (Narumov)

- Morschi Franz (Major Domo)

- Larissa Dyadkova (Countess)

- Svetlana Aksenova (Lisa)

- Anna Goryachova (Polina)

- Olga Savova (governess)

- Maria Fiselier (Masha)

Chorus of the Dutch National Opera

New Amsterdam Children's Chorus

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Mariss Jansons

Direction: Stefan Herheim

Dramaturgy: Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach

Sets and costumes: Philipp Fürhofer

Lighting: Bernd Purkrabek

Muziektheater Amsterdam, 18 June 2016

"Stop that nonsense!"

Who won? The music or the direction? As with many contemporary opera productions this was the question that came to mind at the end of the new staging of Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades by the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam, presented as part of the annual Holland Festival. Music and direction are frequently at loggerheads. The Norwegian director Stefan Herheim doesn't consider the original libretto sufficient. He thinks he has better ideas. Here's one: The Queen of Spades needs to confront us with Tchaikovsky's homosexuality and lifelong emotional distress rather than with the tragic fate of Hermann, Lisa and the Countess as adapted by the composer from Pushkin's tale. There is nothing original about this reinterpretation, yet Herheim fails to convince us he is on a better course. His hand is unsure, his direction fussy, his storytelling fatally confusing. With the superb Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in the pit conducted by Mariss Jansons, Herheim was fighting a lost cause. The music won.

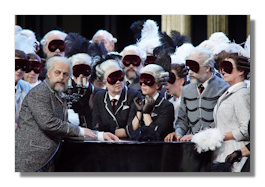

Herheim opens his fantasy world before the music starts by adding a homoerotic scene between a Tchaikovsky lookalike and a man who turns out to be the opera's main hero Hermann. Tchaikovsky pays the man for his services. Mozart's Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen plays on a music box in a birdcage. Worse was yet to come. Herheim puts Tchaikovsky center stage. He is everywhere, all the time. There are countless references, factual or questionable, to the composer's life. He is busy creating the music that plays, he is interacting with the opera characters, he interferes in the story, and if that wasn't distracting enough, every member of the male chorus on stage is a Tchaikovsky clone. "You, you here?" stammers Lisa, looking at the Tchaikovsky figure instead of Hermann at the end of Act II. Spot on, he had no place there. Perhaps worst of all, in Herheim's hands the composer is a pathetic little man. Tchaikovsky is a poor old sucker, a precarious weakling who is tossed around and ridiculed by all, including the audience. By letting him die several times in the opera, Herheim joins the many who hear Tchaikovsky's music from his final years as nothing but a product of a terminally depressed man. He really needs to listen again then. Of course, Herheim readily accepts the debatable fact that Tchaikovsky met his untimely death from deliberately drinking a glass of contaminated water. To make sure we get that message, he repeats it ad nauseam and even lets the old Countess commit suicide by drinking a glass of water. Is this Herheim's answer to the composer's supposed emotional suffering as a homosexual? Frankly, I couldn't care less about what he thinks about it. Nyet, this is the Queen of Spades, based on Pushkin. Not a pamphlet to lament the fate of homosexuals in 19th century Russia. Eventually, he should have listened to the Countess in Act 2: "Stop that nonsense!" Herheim forgot Pushkin, Modest Tchaikovsky's libretto, and he forgot the music. Yet the music won.

Herheim not only adds to the confusion by inventing this fling between the composer and Hermann, the man who is supposed to be in love with Lisa, but also by making this omnipresent Tchaikovsky figure a double of the opera character Prince Yeletsky, who is engaged to Lisa. There are two guys involved, one the baritone Vladimir Stoyanov, the other the pianist Christiaan Kuyvenhoven. I challenge you to tell who's who at the end of the run. Not that it matters. The music won.

Incoherence and absurdity reign in this Queen of Spades. Are we in Tchaikovsky's time? Or rather in the 18th century when Empress Catharina the Great ruled, as supporting roles like Tomsky, Surin and Tchekalinsky seem to suggest? Nobody seems to know or care. It makes the Mozartean divertissement in Act 2 look totally incongruous and by far the weakest part of the production. When Tchaikovsky composed his opera members of the Russian imperial family couldn't be shown on stage. Now the Tsarina turns out to be a man in drag (Hermann – him again). Times have changed.

Every scene plays indoors, mostly in the composer's room. As has become a feature of many opera productions characters are frequently singing words that don't correspond or connect with the stage action. Why is everybody worried about the storm in Act I when they are all inside a house? Why is Tchaikovsky acting like he is suffering from kidney stones while the chorus of children and women are joyfully welcoming a sunny day? The deeper one analyzes, the less Herheim's fantasy hijack makes sense.

Evidently, no expenses were spared for this visually striking production, boasting richly detailed costumes (mostly just black, white or grey) and impressive mobile sets designed by Philipp Fürhofer and evocatively lit by Bernd Purkrabek. Some scenes were effectively staged, with especially a spectacular ghost scene in Act 3, others merely malapropos (the storm in Act 1, the death of the Countess). At the end of Act 2 the chorus appears in the stalls, raising the audience to its feet to salute the Empress, and thus mock Tchaikovsky.

As said, it was the music that offered most joys in this Queen of Spades. Mariss Jansons returned to lead the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra a year after his retirement as the ensemble's Chief Conductor (2004-2015). His affinity with Tchaikovsky has never been a secret. A well-deserved warm ovation from the Amsterdam public greeted his every appearance.

Much of the blurred drama on stage sounded crystal clear in the pit. Jansons conducted with finesse and ear for detail. His flair for tempo and atmosphere was impeccable while the balance between orchestra and voices was in most cases well-judged. Or one could simply wallow in the sonorous beauty of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. The warm strings were divided left-right with the basses in the middle, securing an always solid yet transparent sound. The characterful Dutch woodwinds revealed Tchaikovsky's impressive range of color and the brass and percussion were powerful when required. The modernity of much of the score, especially in the second half of the opera, was fully credited and reminded us this is truly great Tchaikovsky indeed.

Jansons led a largely Slavonic singing cast. Unfortunately, I wasn't entirely convinced by Misha Didyk's Hermann. True, the production allows neither of the protagonists to fully form their characters. They remain as greyish as their costumes and the duets between Hermann and Lisa, scuttled by Herheim's meddling, failed to make the proper impact. I never believed this Hermann ever had any genuine love interest for Lisa – but then again how could he in this ambivalent setup, where he is even declaring his love while facing the audience instead of his beloved. The Ukranian tenor is widely considered the Hermann of his generation, even if to my mind he is as yet unable to replace Galuzin, Atlantov and the likes. His habit to jump towards the high notes, belting them out, grows old quickly, although arguably this could be interpreted as the unbalanced side of Hermann's character. I was more impressed by the young Russian soprano Svetlana Aksenova as Lisa, blending vocal splendor and strength with feminine warmth and a hint of vulnerability.

The best vocal performances were however found among the supporting roles. The Russian baritone Alexey Markov was ideal as Tomsky. His rich, refined voice and commanding stage presence made his ballad of the Countess' past in the first scene absolutely compelling. He was no less delightful in his impish song in Act 3. And what joy to have Larissa Dyadkova as the Countess, a role I first heard her sing some twenty years ago. The quality of her delivery, the complete understanding of her character (to hear and see the Countess recall times long past with the surprise act of Madame Pompadour as a climax, was in itself worth the price of admission) made you nearly forget Herheim's disrespectful treatment of her role. Nothing but praise too for the Bulgarian baritone Vladimir Stoyanov for his acting (as the ubiquitous Tchaikovsky) and his noble rendition of Yeletsky's love aria in Act 2. Both Andrei Popov and Andrii Goniukov, as Tchekalinsky and Surin respectively, were first-rate. Although she was announced as suffering from a slight cold the Russian mezzo Anna Goryachova sang Polina (and her hauntingly sad romance in the 2nd Scene) with melting beauty.

Magnificent work, finally, from the Chorus of the National Opera. They have an important part in the opera and they made every minute count. The male group lamenting the death of Hermann (or actually Tchaikovsky) was especially memorable. The music won.

That we are still enjoying an opera created some 125 years ago is because we recognize and value its intrinsic musical and dramatic qualities, not because it's a vehicle for fanciful producers. Stefan Herheim's staging is in essence not about The Queen of Spades. In spite of the fixation on the composer's sorry plight, imagined or not, this production is eventually about Herheim rather than Tchaikovsky, and I still need to be convinced that's of any consequence. The real Tchaikovsky was alive by his music, magnificently performed by Jansons and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, not by Herheim's multiple clones. "Imagination is fine, as long as it connects with the intentions of the composer", concludes maestro Jansons in an interview in the Dutch National Opera's magazine. If only this advice had been followed.

Copyright © 2016, Marc Haegeman