The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Concert Review

Concert Review

Ashkenazy and Tchaikovsky's Manfred

- Alexander Scriabin: Rêverie, Op. 24

- Wolfgang Mozart: Violin Concerto #5 in A Major, K. 219

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Manfred Symphony, Op. 58

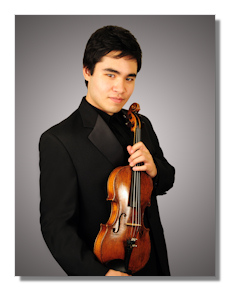

Eric Silberger, violin

Philharmonia Orchestra/Vladimir Ashkenazy

London, Royal Festival Hall, 19 April 2015

Conductors might start to think twice before programming Tchaikovsky's Manfred Symphony in London. Back in November 2002 the famous Russian maestro Evgeny Svetlanov was scheduled to head the Philharmonia Orchestra in an all-Tchaikovsky program at the Royal Festival Hall, with the rarely performed Symphony as the main course. Sadly, Svetlanov died some months before the concert. And now again, it was Lorin Maazel who would guide the Philharmonia through Manfred's dramatic wanderings, yet he passed away last summer. On both occasions Vladimir Ashkenazy, the orchestra's Conductor laureate, jumped in and while both maestros leave an irreplaceable void, there is no doubt that Ashkenazy saved the evenings in the most brilliant way.

Of course, Ashkenazy as well as the Philharmonia share an excellent record with Tchaikovsky's Manfred. Ashkenazy's account with the Philharmonia from 1977 has stood the test of time rather well, while the orchestra also recorded the Symphony with Paul Kletzki and Riccardo Muti – the latter remaining one of the finest versions on disc ever.

Manfred is often considered a pretty hard deal, but Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia made the magic work again. Sonority, orchestral balance and transparency, sense of architecture, well-judged dynamics and keen dramatic timing coalesced into a magnificent reading, viscerally thrilling in its highly-charged dramatic convulsions but also compelling by its emphasis on Tchaikovsky's search for unusual instrumental color. The huge orchestra, anchored on 8 basses, showed no weak spots and responded as a crack team. The quality of the desk leaders (Samuel Coles' first flute and Gordon Hunt's first oboe in particular), the warmth and flexibility of the strings were exemplary throughout. The brass, often helped by Andrew Smith's tremendous timpani, sounded glorious and were well integrated in the orchestral mass.

Ashkenazy knows his orchestra can handle his brisk tempi in the first two movements with little or no loss of detail or accuracy. The swifter than usual tempo for the opening section made the ensuing buildups and sonorous climaxes sound even more ineluctable. He also knows exactly how far to push the orchestra and while tutti generated a lot of heat, they never became shrill or coarse. With playing of this conviction and brilliance all criticism about the work being overlong becomes pointless. Performed without any cuts, unafraid to show its colors and ending with the Royal Festival Hall organ in full splendor: this is, take or leave, Tchaikovsky's Manfred as it should be.

In interesting contrast with the massive forces needed for Manfred, the orchestra appeared before the break in a slimmed-down formation for Mozart's 5th Violin Concerto, with American violinist Eric Silberger as soloist. Silberger is a laureate of the XIVth Moscow International Competition and the Michael Hill International Violin Competition in 2011. He was also mentored by Maazel at his Castleton Festival in Virginia. He played the concerto in what many would consider an old-styled way – and in fact there is no need to imagine anything negative with that: warm, big, unaffected, firmly rooted within the orchestra, with an effective brief cadenza of his own, this was magnificent violin playing. Ashkenazy's accompaniment was equally elegant and balanced.

This performance also reminded us this is a live concert, where even at this level things can occasionally go wrong, as they did in the Rondeau. What sounded like a blackout right before the so-called "Turkish" section threw everybody off track for a few seconds. It didn't spoil an otherwise excellent performance, however, and Silberger returned with a vengeance with some brilliant playing for Mozart's Hungarian rhythms. An appreciative audience was gratified with an encore of Paganini's Caprice #24, which Silberger dedicated to maestro Maazel and dispatched with superb panache.

Most of this concert's program was kept as Maazel had planned it, yet Ashkenazy added the Rêverie from Alexander Scriabin (who died a hundred years ago) as a miniature curtain-raiser. This is a short work – the composer's first attempt at orchestral writing – and unlike some of his more famous later pieces very restrained and devoid of any excesses. Ashkenazy clearly loves this music and by coaxing magnificently transparent string playing, brightened by ravishing winds, he was able to show us why.

Copyright © 2015, Marc Haegeman