The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Burgon Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

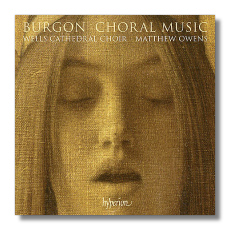

Geoffrey Burgon

Choral Works

- At the round earth's imagined corners

- The Assumption

- Short Mass

- Of flowers and emeralds sheen

- Magnificat

- Nunc dimittis

- As the angels stood

- Apple Blossom

- The Corpus Christi Carol

- The song of the creatures

- Death be not proud

- Come let us pity not the dead

- Te Deum

- Nunc dimittis

Alan Thomas, trumpet

The Wells Cathedral Choir/Matthew Owens

Hyperion CDA67567 72:35 DDD

Summary for the Busy Executive: Little Britten.

Born in 1941, 14-year-old Geoffrey Burgon suddenly found he had the desire to become a jazz trumpeter. He learned to read music, began to compose on the side, and applied to the Guildhall School of Music. Guildhall declined to accept him as a trumpeter, but took him in as a composer. Burgon studied first with Peter Wishart and later with Lennox Berkeley. However, he also pursued his jazz trumpet career while continuing to compose. Not until he reached his thirties did he decide to turn to composing full-time – a gutsy move, considering he had a family to support.

Necessarily, Burgon turned to commercial work, mainly music for film and television, with his best-known scores (if not the best-known fact that he wrote them) Brideshead Revisited and Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. However, he also continued to compose and, more importantly, get commissioned for concert music, a large amount of which was choral music for the church. Occasionally, the commercial and the "artistic" have overlapped, as in the case of the 1979 Nunc dimittis, originally conceived for the soundtrack to Tinker, Tailor and which quickly took on an independent liturgical life. Burgon, by the way, belongs to no church. So the answer to whether a non-believer can compose good sacred music is, "Yes, if the price is right." If nothing else, commercial work will not indulge fuzziness of thought in its guise of profundity. The best practitioners, the most professional, know how to get to the point and to say what they mean. This habit crosses over into Burgon's concert work.

The chief characteristic of Burgon's music is elegance, in the sense that he doesn't waste notes. For those who care, it's tonal. More importantly, it can get inside a listener. His church music, consciously imitated or not, sounds a lot like Britten's, particularly in its fondness for the Lydian mode (F to F' on the white keys of the piano). The raised fourth degree of the scale, usually set against the tonic for the "forbidden interval," gives the music an archaic, not-quite-human quality which can depict equally well the singing of angels in heaven or of mermaids in the sea. However, one notes many differences as well. Burgon's writing isn't as contrapuntal as Britten's, and it doesn't require a virtuoso chorus. However, it does retain its interest for an amateur choir of musically-intelligent adults, one good reason for its popularity, seen most clearly in a work like the 1965 Short Mass – notable not only for its expressive punch, but for its lack of padding and its suitability to liturgical use.

I also praise Burgon's choice of texts. The first-rate attracts him. In this collection, one finds settings of St. Francis, John Donne, and Louis MacNeice, among others. You occasionally hear the bromide that great poetry doesn't "need" music and indeed works against musical setting. This generally indicates that the person advancing this proposition hasn't heard all that many settings and restricts all proper musicalization to something like hymns. Poulenc, Fauré, Finzi, Vaughan Williams, Brahms, Schubert, Schumann, and Britten demolish this prejudice pretty handily. You can never tell a priori what a composer will find a tune for. My favorite tracks on this CD include two famous Donne sonnets ("At the round world's imagined corners" and "Death be not proud"), St. John of the Cross' sensuous "Of flowers and emeralds sheen," MacNeice's "Apple Blossom," and Drummond Allison's heartbreaking "Come let us not pity the dead."

Matthew Owens' Wells Cathedral Choir (which apparently uses girl trebles) has that nice woody English sound. Intonation is dead-on, and textures are clear. I prefer this recording to the Burgon collection on the old EMI CDM566527-2 (nla) with countertenors James Bowman and Charles Brett led by Richard Hickox, both for repertoire and performance, which seemed bland. Here, choir and soloists understand the intensity behind Burgon's scarcity of notes.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz