The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Lambert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

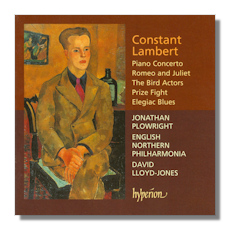

Constant Lambert

Early Works

- Romeo and Juliet

- Elegaic Blues

- Piano Concerto

- The Bird Actors

- Prize Fight

Jonathan Plowright, piano

English Northern Sinfonia/David Lloyd-Jones

Hyperion CDA67545 62:52

Summary for the Busy Executive: Dazzler.

Constant Lambert epitomized the Bright Young Things of the Twenties. Brilliant in everything he attempted – criticism, composition, conducting, piano, painting, and conversation – he shot like a skyrocket, making a lot of sparks early and fizzling as time went on. This fade-out stemmed from three main causes. First, he devoted his energies to establishing British ballet. Second, he became ill from undiagnosed diabetes (he avoided doctors). This killed him relatively young. Third, he overcommitted and overworked. People early on lumped him in with his friend William Walton (who called Lambert the best reciter of Façade). Unlike Lambert, however, Walton plodded as a composer, worrying over practically every note and taking a long time to complete things. This resulted, because Walton was a master, in (no surprise) masterpieces, many of which have achieved a place in standard repertory. On the other hand, Lambert dazzled from the get-go, without apparent effort.

Lambert wrote every item on the program before the age of 23, all but one while technically still a student at the Royal College of Music. Lambert studied with Vaughan Williams, among others, but I doubt the older man taught him much, although Lambert remained an admirer. On the basis of the works here, Lambert had nothing to learn technically, and in any case, Vaughan Williams at the time avoided putting his students through a regimen of technique (he later changed his mind). Further, Lambert took Stravinsky (as Vaughan Williams had earlier taken Ravel) as an influence, and VW always regarded Stravinsky ambiguously, at least all the works after Petrushka.

In one movement with four major subsections (allegro - scherzo - andante - allegro), the Lambert Piano Concerto – not to be confused with the mature Concerto for Piano and 9 Players which appeared seven years later – nevertheless astonishes. First, something so assured and architecturally sophisticated comes from a 19-year-old. Second, it sounds like little else in British music of the time. I hear both Stravinsky and the Prokofieff of the First Piano Concerto, as well as a bit of Milhaud and Ravel. Third, Lambert gets a terrific amount of color from a limited, highly unusual orchestration: piano, string orchestra, two trumpets, and timpani. The piano writing is idiomatic, idiosyncratic, and brilliant. The score doesn't exhibit the same psychological complexity as the later concerto, but it wows as a dazzling divertissement.

The short ballet Prize Fight, like the Piano Concerto, comes from 1924, although Lambert revised it three years later. It shows the strong influence of Vaughan Williams in its use of English and Irish folk-derived tunes and in its portrayal of a boxing match (VW's opera Hugh the Drover began with the composer's itch to set a prize fight to music). The match pits a Brit, represented by a rough English rustic dance, and a Yank, who dances to a theme with the same rhythm and general shape as "When Johnny Comes Marching Home." It differs from VW in its satiric sensibility, similar to Lord Berners and Les Six. Full of comedy orchestration (including wa-wa trumpet), the work begins with a skewed English country dance. The individual numbers are separated by broadly parodistic, illustrative mime scenes. One can hear clearly, for example, the fight announcer. The fight itself comes out in the contrapuntal "combat" between the two themes.

Don't take the title of the vivacious overture The Bird Actors too seriously. It previously served as the finale to Lambert's ballet Adam and Eve (more below). After the ballet changed, Lambert made this finale an independent work and gave it the title of a Sacheverell Sitwell poem. A virtuosic demonstration of complex counterpoint and clear scoring, it has obvious affinities with Holst's and Vaughan Williams's brand of neoclassicism – the Fugal Overture, for example. This gem sparkles with memorable themes. I complain only that I want more.

Lambert seldom indulged in illustrating plot. More abstract musical considerations attracted him, with the full-length ballet Romeo and Juliet a case in point. Lambert originally wrote it to a libretto about Adam and Eve. However, in 1925, when Lambert was all of 20, Diaghilev came to London to produce a season of his company, looking for an English work on an English subject, a canny box-office ploy to please the home-town crowd. Walton had an audition and asked his buddy Lambert to come along for moral support. Walton botched his audition, and Diaghilev asked Lambert whether Lambert might have anything for him. Lambert played parts of the ballet and snagged the Russian's interest. However, since he wanted an English subject, Diaghilev then and there swapped Adam and Eve for Romeo and Juliet. Even then, he fiddled with that plot, which became about a ballet company putting on Romeo and Juliet. Lambert's music (like a lot of music, actually) fitted one story as well as another. Thus Lambert became the first of only two British composers (the other, the Satiean Lord Berners) commissioned by Diaghilev.

At any rate, don't go looking for musical drama or psychological insight. This music could depict any plot, as long as it matched the general mood of the story. In other words, it matches A Midsummer Night's Dream as well as R & J. Lambert conceived the music as pure dance, as one can also tell by the titles of the numbers: "Rondino," "Gavotte and Trio," "Siciliana," and so on. The music breathes the same atmosphere as Stravinsky's Pulcinella, only here the themes all originate with Lambert and he doesn't occasionally reach for something grander, like Stravinsky. The ballet keeps an intimate, almost toybox scale, very similar to Walton's much later Music for Children.

The Elegiac Blues of 1927 (originally for piano, but orchestrated in 1928) memorializes the African-American entertainer Florence Mills, who died heartbreakingly young, mainly from overwork, that year. Mills had just left London for the States, and Lambert may well have seen her. Duke Ellington's Black Beauty (Portrait of Florence Mills) also remembers her. Lambert, brilliant and a true eccentric, was an early British fan of American jazz, especially of Ellington. He manages to breathe a little smoke into a classical orchestra. Furthermore, the piano original captures the spirit of Ellington in the late Twenties, so much that no one would blame you if you mistook Lambert for Ellington, at least through the first couple of phrases.

Praise to Lloyd Jones and Hyperion for their Lambert series. The performances have ranged from very good to superb. Concerto soloist Jonathan Plowright plays with panache. He gets and communicates the audacity of Lambert's writing. Lloyd-Jones and the English Northern Sinfonia play with sharp attack, clear textures, which allow Lambert's wonderful counterpoint to come through, and convey the considerable wit in these scores. I hope Hyperion gives us more.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz