The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

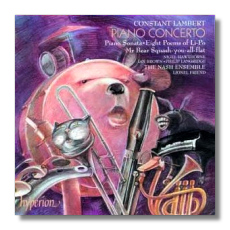

Constant Lambert

- Concerto for Piano and Nine Players

- 8 Poems of Li-Po

- Sonata for Piano

- Mr Bear Squash-you-all-flat

Ian Brown, piano

Philip Langridge, tenor

Nigel Hawthorne, narrator

The Nash Ensemble/Lionel Friend

Hyperion CDA66754

I suppose Constant Lambert is best remembered for his brilliant (and occasionally wrong-headed) book of criticism, Music, Ho!, one of the first tries in English at summing up modernism (it appeared in the 1930s). However, he also left behind a small but startlingly original catalogue of work, in many ways paralleling Walton. The originality shouldn't surprise one on learning that Lambert's musical heroes included both Sibelius and Duke Ellington. As a composer, Lambert was an almost-pure Stravinskyite, with occasional raids into Russian Nationalist pastiche, particularly for his film scores. Why his music hasn't caught on with the larger public, I can't tell you.

A composing prodigy, Lambert began to produce astonishing work in his teens and twenties (he died at 46). The latest work on this disc, the piano concerto – actually, it turns out, the second of Lambert's essays in the form, since there's also an unpublished one completed at 19 – comes from 1931, in Lambert's 27th year. The earliest, Mr Bear Squash-you-all-flat, followed Walton's Facade, in that it is scored for a small chamber group of diverse instruments and uses a speaker. It's not quite pure melodrama, since at certain points the speaker declaims to the rhythm of the music. Combining spoken word with music spawns problems that Lambert doesn't really solve, chief of which is that when someone speaks, the music fades into the background, as in movie underscoring. Walton's rhythmic declamation in Facade, Carl Sandburg's Sprechmusik recital of Copland's Lincoln Portrait (which, by the way, Copland hated), and certain works of Orff and Toch are the only really successful examples I can think of. All of them distance the words by treating the voice as another instrument. Lambert's music, however, to me stands on its own wonderfully well – a stunning array of various and precisely-imagined sounds. Nigel Hawthorne basically chews the scenery with a trifle – a bit like British pantomime, which either you have a taste for or you don't. I don't. Still, the music itself is incredibly winning.

Chinese poetry – Li-Po's in particular – has attracted composers of wildly varying temperament, from Mahler to Bliss to Britten to Wilding-White. In his liner notes, Giles Easterbrook notes with amazement that the Eight Poems of Li-Po are Lambert's only mature songs. I'm less amazed, since I find more interest in the instruments than in the vocal line. Indeed, as settings, they take the easy out of quasi-recitative, without one real tune. Lambert wrote most of them in the throes of an unrequited infatuation with the film star Anna May Wong, but you'd never know it from the voice. All the love-making comes from the instruments. Chinese poetry hardly ever prescribes what you must think. Instead, it invites you to meditate and to wait for enlightenment from within yourself. Thus we have the great passions and lettings-go of Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde and the stoicism and gentle humor of Britten's Songs from the Chinese. Lambert's music is exquisitely sensuous, but, like Chinese poetry, it too has a shell impervious to a take-no-prisoners intellectual raid on understanding. It is static and lovely, perhaps too much so. At one point, I heard John Wayne's "Oh, haul off and kiss her!" from Ford's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. Easterbrook suggests that the actress was more interested in money than in True Love. The music's passivity makes me suspect that Lambert was waiting to be seduced. Tenor Philip Langridge does what he can with the little he gets.

I find the Piano Sonata interesting mainly as a transitional piece. It appeared between two flat-out masterpieces: The Rio Grande, a tour-de-force for chorus and orchestra, and the Piano Concerto. The Rio Grande uses jazz as artifice, to match the artifice of Sacheverell Sitwell's text, much as Stravinsky uses ragtime in L'Histoire du soldat. With the sonata, however, jazz becomes assimilated into Lambert's musical thinking, mainly in his rhythms and, to some extent, in blues-inflected Impressionist harmonies, not unlike Ellington's. Lambert is less concerned with wit and musical puns and starts not to think consciously of jazz at all, but of expression. Jazz has become part of that expression. There's much of interest in the structure and in the imaginative piano writing, as well as in its pointers to the concerto, but somehow it doesn't come off emotionally. Easterbrook and others suggest a dark, Mephistophelean undercurrent, which, if so, has escaped me.

No doubts at all about the concerto, however. Despite its chamber instrumentation, it feels like a concerto, with virtuosity from the soloist and power not so much from instrumental mass, but, again, from powerfully imaginative instrumental color. Not only is the jazz element completely absorbed, but Lambert puts it in the service of his expressive needs. He composed the piece in the aftermath of the suicide of his close friend Philip Heseltine (better known as the composer Peter Warlock). Heseltine and much of his circle decided to think of themselves as doomed poets, like the Pre-Raphaelites and the Decadents. For their art, they would commit Great Sins. It's not really a profession to aspire to, and it's interesting that, the quality of their art aside, most of them became mere tiresome drunks and addicts. Still, Heseltine infests the concerto like a malignant sprite. Here indeed is a grotesque, dark undercurrent, especially when you realize how much of the concerto uses distorted version of Warlock themes. Warlock's rapt "Frostbound Wood" (which begins "Jesus met me in the frost-bound wood") Lambert twists into a jazzy raspberry. Parts of Warlock's "Balulalow" also show up. In fact, the concerto's generating motive turns out (by the last movement) to have been an angry variant of this cell. Easterbrook also claims to hear parts of Warlock's bleak song cycle "The Curlew." I don't hear it myself, but the end of the slow movement is pure psychic desolation, whether Warlock's or Lambert's own. Ian Brown and the Nash Ensemble turn in a bang-up job, with crisp rhythm and wonderful ensemble work. It beats the only other performance I know, pianist Richard Rodney Bennett and players from the English Sinfonia led by Neville Dilkes (Polydor LP SUPER 2383391, not currently available). Conductor Lionel Friend finds the hysteria beneath the concerto's very urbane surface.

In fact, the Nash Ensemble turns in first-class performances throughout, beautifully clear, with loving attention to Lambert's subtle shifts of scoring. They play as well as anybody and better than almost anyone. Engineering is excellent, with no mucking around with electronic sonic Valhallas.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz