The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Thea King

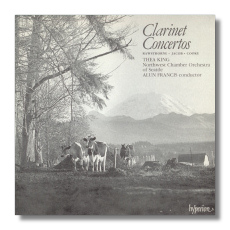

Three English Clarinet Concertos

- Alan Rawsthorne: Concerto for Clarinet & String Orchestra

- Gordon Jacob: Mini-Concerto for Clarinet & String Orchestra

- Arnold Cooke: Concerto for Clarinet & String Orchestra

Thea King, clarinet

Northwest Chamber Orchestra of Seattle/Alun Francis

Hyperion CDA66031 57:12

Summary for the Busy Executive: Elegant and fun.

Players as much as instruments inspire composers of concertos. British composers were especially lucky in their clarinetists, oboists, horn players, and violists. There have been at least three dominant British clarinetists: Frederick "Jack" Thurston, Gervase de Peyer, and Thea King, and admiration for their playing has led to the items recorded here. Thurston, the grand old man of the group, got works from Rawsthorne as well as Finzi's masterpiece. Thea King, Thurston's pupil and wife, got the Jacob "mini-concerto," while Cooke wrote his concerto for de Peyer. All three composers, however, languish in a critical limbo. About the only recordings they get come from British labels. Unlike Vaughan Williams, Britten, Walton, and Tippett, they haven't a firm hold on the international music scene – a pity, because they all write wonderful stuff, usually neoclassical in craft though neo-Romantic in spirit – and all, to some extent, fall into the limbo of "composers' composers."

Rawsthorne's stock has probably risen the highest of the three. He had an enviable reputation, once upon a time, as a symphonist of real individuality, like Simpson today. His neoclassicism comes essentially from Hindemith, and his idiom sounds a little like Walton because of it. However, with the notable exception of one piece that I know of, Street Corner Overture and some of Practical Cats, his music lacks the physical ebullience of Walton's. He strips his music to the bone, and his work usually testifies to an austere, guarded personality. Those who take Mozart's concerto as an archetype may find Rawsthorne's example a bit surprising. The sun seems to have forgotten to rise, despite some sprightly rhythms. The proportions and the means are very modest, but Rawsthorne manages to suggest great weight without actually piling on the musical pounds. Rawsthorne subtly links its four movements, so that the end of one "fits" the beginning of the next. A current of worry runs through the first-movement "Preludio." The "Capriccio," a scherzo on a three-note idea, jokes, but the laughs are grim and short of breath. The slow movement "Aria," finely adumbrated by pizzicato bass at the scherzo's end, is a grave conversation among the string sections and their principals. The clarinet, to a surprising extent, stays out of things here. When it does sing, it uses its low register. The "Aria" weeps over a bleak landscape. The finale, "Invention," bustles like a wasp guarding its hive. It's not exactly ill-humored, but you can't really call it jolly fun, either.

Gordon Jacob seems to have gotten stuck in the pigeonhole of "Craftsman." That is, the music, though well-made, doesn't go very deep. I consider this a half-truth from lazy people. The true part is that Jacob's music is indeed well-made. As to its alleged lack of depth, I contend that his output is too little known for generalization. Like so many of his generation, Walton and then Britten and then Tippett eclipsed him. After all, he did study with Vaughan Williams, who by the older man's own admission had nothing to teach him in terms of technique, and his songs, at any rate (if you can find them), are wonderful. I especially recommend his three Blake settings for high voice and string trio. It could very well be that mainly the light stuff gets recorded. The "mini-concerto" makes no claims to profundity. The music seeks, in Debussy's happy phrase, "humbly to please." Jacob has essentially written four miniatures in a kind of Mendelssohnian fast-slow-allegretto-fast progression. He wrote it in 1980 (Jacob died in 1984), but the work harkens back to the heady days of the Twenties. The neoclassicism, as is immediately evident, has more in common with home-grown models than with anything on the continent: Vaughan Williams' Concerto accademico and Holst's Fugal Concerto, for example. In the liner notes to the recording, Jacob likens his work to "a miniature symphony or sinfonietta," mainly because the movements show the bare bones of symphonic classical forms. However, I think this misses the point. Unlike Rawsthorne's slightly-longer work, Jacob's mini-concerto doesn't move like a symphony. Each of its four movements really just states a group of ideas – exposition without development. I don't put Jacob down for this. The ideas are wonderful. It's as if he has found for any point the right note. He has made little jewels of melody and elegant settings to surround them. The lovely slow movement – at three-and-a-half minutes the biggest of the four – manages to say a lot with very little. The first and third movement will charm you out of your drawers. The tarantella finale gets the body moving. Jacob expressed his amazement that King took it much faster than he dared to specify. King certainly sails through with apparent ease. However, Charles Russo on Premier PRCD1052 beats her by about fifteen seconds. Nevertheless, overall King gives a more elegant, more poetic account. She finds depth in the music that Russo misses. King's performance is the one to have.

Arnold Cooke actually studied with Hindemith. Everything I've heard has been beautiful, in the way of a Brancusi sculpture. While one can find superficial resemblances of idiom, in particular a fondness for fourths, and a seriousness of attitude, the music doesn't really come across as derivative – that is, without a reason of its own for being. Rather, it compels on its own. I actually prefer it to Hindemith's clarinet concerto. Cooke tends to sing more and to dance less than Hindemith. The counterpoint intensifies rapt singing, rather than exciting rhythm. For some reason, however, it's harder to find work by him than even by Rawsthorne or Jacob. He has written the most ambitious concerto of the three – at slightly under a half-hour, the longest by far. Like the Nielsen, it's genuinely symphonic and has a great deal of matter. It divides into three movements – Allegro, Lento, Allegro vivace. Despite the modesty of its forces, the concerto gives its soloist an heroic part of great substance. It's not a young hero who slays dragons, as in, say, the Strauss first horn concerto, but a hero moving through a darker, uneasier, more adult world. The strings shoulder as much of the argument as does the soloist, particularly in the first movement, but the contrast of timbre ensures that we never really forget that the clarinetist is first among equals. The slow movement sings mainly of serious matters, but one also hears the call of the blackbird, which the composer heard in his garden and noted down. Curiously enough, the blackbird's call has ties to the main subject of the movement. The finale is the most Hindemithian part of the concerto, but what the hey? I certainly won't sniff at more good Hindemith, particularly something as playful as this movement. I particularly like some surprising and vigorous ear-stretching modulations. As I say, this concerto, by its span alone, makes greater demands than the other two on the musicianship of the soloist. King, Francis, and the Seattle players do a handsome job.

The sound, as you would expect from Hyperion, is smooth and creamy.

Copyright © 2003, Steve Schwartz