The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Jacob Reviews

Somervell Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

English Clarinet Quintets

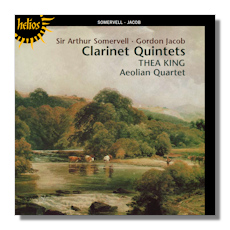

- Arthur Somervell: Clarinet Quintet in G Major (1913)

- Gordon Jacob: Clarinet Quintet in G minor (1942)

Thea King, clarinet

Aeolian Quartet

Helios CDH55110 57:44

Summary for the Busy Executive: Sit back and enjoy.

England in the Twentieth Century enjoyed a rich native musical creativity, with at least seven major composers beginning with Elgar and ending with Maxwell Davies. Unfortunately, only one or two composers at any one time tended to crowd out everybody else. It says a lot when composers like Rawsthorne and Simpson become afterthoughts because they had the misfortune of writing during the time of Vaughan Williams, Walton, Britten, and Tippett. Unfortunately, our memory banks seem capable of holding on to only one or two names at a time. I can't make a case for either Arthur Somervell or Gordon Jacob as artistic giants, but a healthy musical life requires more than acquaintance only with the super-great. We need all sorts of music because our lives change from day to day, if not hour to hour. As much as I adore Bach, a steady intake of nothing but the St. Matthew Passion would pall, become something like a prison sentence, drive me insane, or numb me to the point where I no longer really listened. It's like reading only the Bible or only War and Peace. It's bound to turn you peculiar. Most of us need to clear the mental palate, and we needn't throw away excellence to get variety. Excellence, after all, turns up in many forms.

Arthur Somervell studied with Charles Villiers Stanford, one of the great engines of the British musical renaissance, both as a composer and teacher, as well as with Hubert Parry. Early on, the Royal College of Music appointed him to the faculty, where he worked on musical education projects. As a composer, he concentrated on choral music and song, much of which he intended for amateurs and schools. However, the Clarinet Quintet reveals not only his thorough training, but his capacity for poetry. The score, a lyric wonder, contains four beautiful, solidly-made movements. It may not have the depth of the Brahms Clarinet Quintet, but very few works do. The idiom interested me, since it seemed to come from at least two generations previousy – somewhere between Schumann and very early Brahms. It may have led to the work's neglect. Of course, as time passes, the anachronism matters less and less. I'm delighted to have another wonderful "19th-century" chamber work, with the lyricism of Schumann and the architectural steel of Brahms. It lifts my heart.

Gordon Jacob, another Stanford pupil, also studied with Howells and Vaughan Williams. The latter reported that he had nothing to teach him, at least in terms of technique. Jacob, for his part, seems to have gotten little from Vaughan Williams's formal instruction. He said that the older man at that time distrusted technique and hesitated to come down too hard on his students for fear of stunting their creativity. Jacob himself joined the composition faculty at the Royal College of Music. He numbered among his students Malcolm Arnold and Elizabeth Maconchy. His own compositions are well-made, with a keen awareness of instrumental capabilities, colors, and blends. His most successful pieces, unfortunately, are orchestrations of others. My impressions of his music, naturally, come from what I've heard, and recording companies tend to issue his lighter stuff. The large pieces that have come my way – the two symphonies and the first viola concerto – strike me as dutiful. I wait in vain for a spark. On the other hand, his less ambitious scores disclose a singular fancy, as well as exceptional structural clarity, concern for a good tune, and thematic control. Jacob's Clarinet Quintet aspires to less than the Somervell. It lies well within the British mainstream of the Forties, but without the punch of Walton, Britten, Tippett, Alwyn, or Vaughan Williams. Nevertheless, it's amiable and makes a nice bit of listening if you're not in the mood for Peter Grimes.

Thea King has probably succeeded her late husband, Frederick Thurston, as the foremost English clarinetist. Her repertory ranges very widely, and she brings superb tone and musicianship to everything she does. The Aeolian Quartet becomes more than a simple accompanist, but a full partner in the music. I complain only about the sound – a lot of treble – but I managed to get used to it.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.