The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Butterworth Reviews

Gurney Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

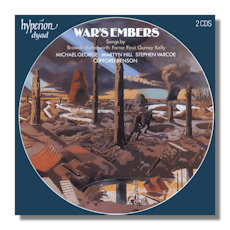

War's Embers

Songs from World War I

- Frederick Septimus Kelly: Shall I compare thee?

- George Butterworth: Requiescat

- Gerald Finzi: Requiem da Camera

- William Charles Denis Browne:

- Diaphenia

- Epitaph on Salathiel Pavy

- To Gratiana dancing and singing

- Ernest Farrar:

- Brittany

- Come you, Mary

- Vagabond Songs

- Who would shepherd pipes

- Ivor Gurney:

- Blaweary

- By a bierside

- Cathleen ni Houlihan

- Edward, Edward

- Epitaph in old mode

- Even such is time

- Fiddler of Dooney

- Goodnight to the meadows

- Ha'nacker Mill

- Hawk and buckle

- In Flanders

- Last hours

- Most holy night

- Nine of the clock

- Orpheus

- Severn meadows

- Sleep

- Spring

- Tears

- The Boat is chafing

- The Night of Trafalgar

- The Ship

- Thou didst delight my eyes

- To violets

- Twa corbies

- Under the greenwood tree

- You are my sky

|

|

|

Martyn Hill, tenor

Stephen Varcoe, baritone

Michael George, bass

Clifford Benson, piano

Hyperion CDD22026 54:34 + 63:05

Summary for the Busy Executive: The real lost generation.

When Houdini toured the United Kingdom in the Twenties, the scarcity of young men in his audiences shocked him. World War I had decimated Europe's youth. Inevitably, young poets, artists, and composers turned up as part of the dead and damaged. This wasn't a group of rich and/or artsy drifters in an existential funk, but a generation thrown away, wasted, and literally lost. This two-CD set from Hyperion presents a musical sketch of the English casualties.

Because almost all of these men died young, the program makes us think of possibilities rather than of actual accomplishment. There are four major exceptions: Gerald Finzi, George Butterworth, Ivor Gurney, and W. Denis Browne. Finzi seems an odd choice, since he was too young to serve in the war, but the war killed off several of his friends and one of his teachers and left him psychologically scarred. With Butterworth, one wonders what might have been. At the time of his death, he was probably the most original and accomplished composer killed, even though at the time he had written only miniatures - songs and brief orchestral pieces - but miniatures exquisitely wrought. The war spared Gurney's life but took his sanity. From 1922 to his death in the Thirties, he was confined to an asylum. Nevertheless, he had mastered two arts: poetry and music. He counts as one of the finest songwriters England ever produced and competes with Finzi as a kind of English Fauré. His poetry, although not playing in quite the same league as his music, is nevertheless both quirky and solidly built. He is one of the great Georgian poets and, with Wilfred Owen, perhaps the best of the war.

These CDs also give us a musical snapshot of the time, one probably closer to life than our usual concentration on masters like Elgar, Holst, and Vaughan Williams. One of the things that struck me, at any rate, was how minor the minor poetry they tended to set is. Names like Wilfrid Gibson, John Davidson, E.V. Lucas, John Freeman, J.C. Squire, and Norman Gale generally run a line of pastel pastoralism or Boy's Own Paper heartiness and often inspire merely songs similarly faded and exhausted. I hear the parlor musicale a lot in so many of the songs by Farrar, Kelly, and even Browne and Gurney. I can practically see at the spinet my Aunt Ida sliding into "Pale hands I loved beside the Shalimar."

The songs of Farrar (d. 1933) show the influence of his teacher Stanford. Among the songs included, one finds two poems also set by Vaughan Williams: "Silent Noon" and "The Roadside Fire." The comparison doesn't help Farrar. The Vaughan Williams settings are two of the finest English songs I know. "Silent Noon" in particular seems to stop time. Vaughan Williams' "The Roadside Fire" is one of the rare songs not by Schubert that can be called genuinely Schubertian, reminding one of "Wohin" from Die schoene Müllerin. Not only is Farrar's use of the Stanford idiom less distinguished, he doesn't really seem to be a songwriter. The sonnet structure of "Silent Noon" foxes him, and the song is full of marking time, petering out, and starting again, rather than a melody taking us from here to there. Farrar also can't seem to find the right tempo for "The Roadside Fire," and again his musical structure fights unconvincingly with the verse structure. The song comes across as manically dippy.

Frederic Kelly (d. 1935) has had a couple of songs in the repertory of singers like Tibbett, Thomas, and Baker. They are, to use Douglas Adams's phrase, "mostly harmless." The CD, however, presents a rather toxic setting of "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day." It's filled with a chromaticism that derives not from Brahms or Wagner, but from sources like Gounod and Franck – a meandering, weak-tea affair. It's the kind of song that, unfortunately, seems to write itself.

W. Denis Browne (d. 1927) counts as a new discovery for me. By his death, British music lost something fine. In addition to about half a dozen songs, four of which appear on this program, he also wrote music criticism, mainly to make ends meet, and he gave the British première of Berg's piano sonata. Clearly, this mind doesn't run along well-worn paths. His own idiom, in retrospect rather conservative, nevertheless shows signs of trying to stretch to its limits, and his ability to create unusual form (or echo the unusual forms of his texts) is nothing short of masterful. He also chooses his poems well: works by de la Mare, Ben Jonson, Henry Constable, and Richard Lovelace. This is a born songwriter. Unlike and Farrar and Kelly, in which the harmony dominates, Browne's songs give the impression that melody and harmony were born at the same time. For me, these are the best-crafted songs (if not the greatest) on the album.

Ivor Gurney's (committed 1932, d. 1947) work has appeared on many recordings. His early songs sound like his teacher Stanford, but there's a genuine power to them as well as a sensitivity to poetic rhythm not often found in Stanford. Gurney, however, hasn't the formal grasp of Stanford, although he is formally aggressive, and sometimes that blows up and sinks the song. Like Browne, he shows real perception in his choice of authors, and not always easy, "song-like" ones: Graves, Masefield, Yeats, Hardy, Herrick, as well as the usual Elizabethans. While he hasn't the compositional skill of Browne, he nevertheless comes up with songs of real genius. For me, his greatest is "Sleep," to words by John Fletcher, with a melody that reminds me of a Dowland ayre, though in a near-Warlock idiom. His setting of "To Violets" tames Herrick's willful meter to a natural reciter's rhythm. John Freeman's poem, "Last Hours," is free verse, which Gurney again shapes into a convincing song.

Finzi and Butterworth (d. 1931) get one song apiece. Finzi's "Only a man harrowing clods," text by his favorite Hardy, comes from an unfinished Requiem da camera. Finzi completed everything but the orchestration. Typically, he put it in a desk drawer and forgot about. It stayed there until after his death. The Requiem has since been orchestrated (by Philip Thomas) and is available on Chandos CHAN8997, along with choral works by Britten and Holst. Butterworth's "Requiescat" (words by Wilde) isn't his best song by a long shot, but it's not nothing and doesn't often get recorded. It's Butterworth without the folk influence, but one can see in the song why folk music attracted Butterworth in the first place: its directness, its affective economy, its clarity of idea.

Three of the best singers in Britain – Stephen Varcoe, Michael George, and Martyn Hill – split the honors. I've praised Varcoe before for his Grainger collection on Chandos, but all three share the same set of virtues: complete control over the singing line and phrase, clear and natural diction, the ability to crescendo and diminuendo from anywhere in the phrase, and the intelligence to do so at right place to make a genuine point. None of them, as far as I can tell, have big enough voices for opera, but I can't think of a current opera star who sings as well. Clifford Benson is known for his accompaniment of wonderful singers (he's recorded Finzi's Earth and Air and Rain with Varcoe) and for his participation in chamber music. He brings to all of his performances a sensitivity to musical line worthy of Chopin and Brahms. I'd love to hear him solo some time.

The sound is perfect for these forces.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz