The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Martin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

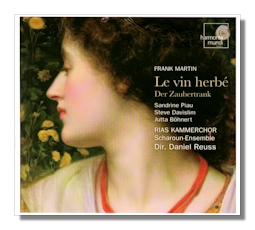

Frank Martin

Le vin herbé

- Jutta Böhnert, soprano (Branghien)

- Sandrine Piau, soprano (Iseut)

- Hildegard Wideman, alto (Iseut aux blanches mains)

- Ulrike Bartsch, alto (Iseut's mother)

- Joachim Buhrmann, tenor (Kahedrin)

- Steve Davislim, tenor (Tristan)

- Jonathan E. de la Paz Zaens, bass (King Marc)

- Roland Hartmann, bass (Duke Hoël, old man)

Berlin RIAS Chamber Chorus

Scharoun Ensemble/Daniel Reuss

Harmonia Mundi HMC9001935.36

Le vin herbé was written by the reclusive Swiss composer, Frank Martin (1890-1974), in the late 1930s. It was conceived originally in response to a commission from Robert Blum for his Züaut;rcher Madrigalchor – as a miniature, at 30 minutes. And with minimum instrumental forces supporting a dozen voices. As Le philtre, Martin's first exploration of the Tristan and Isolde story was restricted to the love potion part of Joseph Bédier's retelling and was first performed in April 1940.

But Martin – not wanting to relinquish his fascination with the legend – decided to expand what he'd written across multiple "tableaux". He used two chapters of Bédier's book ("La forêt du Morois" and "La mort") to create a work which was at once more substantial (a prologue; three sets of six, five and seven scenes; an epilogue) and even more distilled, more intense: Le vin herbé concentrates as much on death as on love.

In setting medievalist, Joseph Bédier's, version Martin further distanced himself from Wagner's by looking further back in time (to sources by Béroul and Eilhart von Oberge) than the early thirteenth century poem by Gottfried von Strassburg which had inspired the German composer: Martin's sensibilities objected to the Nazis' "hijacking" of Wagner by the time he was working on Le philtre and Le vin herbé. What's more, both the original and the subsequent performance requirements were for something much closer to a chamber work, albeit of a dramatic nature and on a grander scale (twelve voices), than had become the norm in Romantic grand opera.

So – puns aside – Le vin herbé must be approached as a finely distilled, refined and concentrated work. It's more akin to the Lied of Schubert than the song-cycles of Mahler in the way it conveys emotion. With a prominent part for piano, it's almost the world of Britten's chamber operas and church parables. The richness of the harmonies and textures, prevents Le vin herbé from being called "minimalist'; yet it has the qualities of accessibility, openness and detachment that make it almost Stravinskyan in atmosphere, though warmer and nowhere near so austere. This recording (listen to the urgency of the fourth part of "La Mort', [CD2 tr.4]) makes it clear that Martin was not reacting to the richness of the Romantics in the way Stravinsky did. But was himself as romantic as Berg in his use of melody and harmony.

Key to the achievement of such a feel of astringency yet passion is the dual use of the principals (Iseut, Tristan, Branghien etc) as members of the chorus commenting on their own actions. This conveys distance and detachment in the same way as does the fact that (interior) monologue is preferred to dialogue. The result is not coldness or dispassion. But a heightening of emotion, a focus on the "plight" of the lovers and the consequence of their love that is so tight as to become inescapable.

Nor must a good performance of Le vin herbé be all atmosphere. It should have the same rigor as should a telling Pelléas et Mélisande, with which work – in a quieter sort of way – it has something in common. Above all, there is a defined and necessary structure to the work… the love, the potion first; King Marc's forgiveness second (a role wonderfully played – and with great dignity and gravitas – by Jonathan E. de la Paz Zaens); and the climactic death in the third part. Only by tying these three stages together around what we spectators know can Le vin herbé make sense. This conductor Daniel Reuss has achieved remarkably well here. The action never moves too fast for us to feel empathy. But such empathy as is elicited has every good reasonÉ low piano throbbing, cello plaintiff yet full of momentum; upper strings restless yet tidy. Quite something to sustain for almost two hours. Yet it is very well sustained indeed on this set.

Further, it is the fully intentional ease with which these emotions are exposed that makes this recording such a success… informal speech patterns and rhythms; an organic flow of ideas and feelings against a familiar story; color borne as much of departure from twelve-note technique in the interests of apparent experimentation as of adherence to it; almost unashamed escapism from the horrors of wartime Europe – making such emotions as love and (presumed) reconciliation all the more treasured. Reuss and his soloists in particular bind us back into things with which we want to be bound.

This excellent recording avoids all the pitfalls of claustrophobia, histrionics and maudlin. Listen to the third scene in "la Mort", [CD2 tr.3], for example: the chorus obviously has pity, empathy, resignation, a sense of loss. But the tone is a "knowing" one; the manner apparently uninvolved enough to make us trust that their commentary is very worth listening to. This has much to do with rhythm and a delicate hanging back. But also with the unambiguous articulation of the text. The delivery – plainly yet arduously supported by the strings – is indeed concentrated, finely balanced. Throughout the performance the words fall upon us with just the right amount of declamatory zeal and introspection. In short, it's all beautifully played and sung by the soloists and the Berlin RIAS Chamber Chorus and Scharoun Ensemble. The pace, the gradual and unstoppable unfolding of the disaster, are carefully handled so as to make us feel, indeed, that we are part of the experience. True, Reuss has chosen to use more singers (25, including soloists) than Martin conceived. The string septet and piano (persuasively played by Majella Stockhausen-Riegelbauer) do more than provide an accompaniment. They, too, seem part of the tragedy.

But this is not a re-interpretation, a departure from Martin's precise intentions. By virtue of the concentration on and attention to musical and dramatic detail by all concerned, it's actually a more faithful account than any previously recorded. There is otherwise only the Cantori di New York one on Newport Classic (85670) available now. So this two-CD Harmonia Mundi offering will anyway be regarded as the set to choose, if not, perhaps, a definitive recording.

It's a close and resonant one, made in the Berlin-Dahlem Jesus-Christus church. There is an excellent and perceptive introductory essay in the booklet, as well as the text in French, English and German. If you've been waiting for a fresh and utterly convincing account of this unfashionable-at-the-time yet now timeless work which reveals and celebrates Frank Martin's particular strengths, then you'll be pleased to know that this set can be recommended without hesitation. It's scarcely spectacular. Nor yet ostentatious. But this Le vin herbé surely says everything the composer wanted to say. And in a totally convincing, beautiful and contemporary way.

Copyright © 2009, Mark Sealey