The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- J.S. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

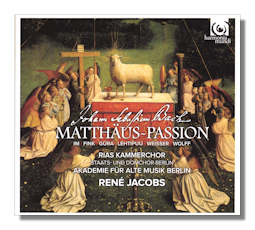

Johann Sebastian Bach

St. Matthew Passion (Matthäus-Passion), BWV 244

- Bernarda Fink (mezzo-soprano)

- Fabio Trumpy (tenor)

- Topi Lehtipuu (tenor)

- Werner Güra (tenor)

- Konstantin Wolff (baritone)

Berlin RIAS Chamber Chorus

Berlin State & Cathedral Choir

Academy for Ancient Music Berlin/René Jacobs

Harmonia Mundi HMC902156/7 2CDs

Also available on 2 Multichannel Hybrid SACDs HMC802156/8 with "Making of" DVD:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

One reason to supplement the thankfully crowded catalog of Matthew Passions (almost a hundred are currently available) is to have something new and/or distinctive to add and communicate. In the case of this well-produced, well-conceived and well-performed set on Harmonia Mundi three characteristics are obvious from almost the first few bars: a quiet urgency to convey the intricacies, intimacy and enduring delicacy of the work; a pace and sense of structure which nevertheless concentrate on the Passion's dignified whole; and a concern to re-evaluate such aspects of the work as the spatial interrelationship between choirs, soloists and instruments.

Jacobs has been fascinated by the Matthew Passion since childhood. Indeed, he first encountered it as a performer, a soloist in an earlier (but nla) celebrated version by Philippe Herreweghe. There is a certain confidence and control in the conductor's approach that reflect such a lifelong involvement. At the same time there are passages ("So ist mein Jesus"/"Sind Blitze, sind Donner" [CD.1 tr.27]) where he seems to be saying, "This is as far as I have come at this point in my understanding; I'm leaving some nuances up to you, as listeners; I shall return". "Raw" is not the word. But this is by no means a performance or recording that aims at definitiveness. Examples abound of when individual instruments, groups of textures, and articulation of sounds are gently and lovingly emphasized… the concentration in "Mein Jesus schweigt" followed by "Geduld" [CD.1 tr.s 34,35] is palpable – and to a real purpose.

Some of the tempi may surprise some listeners. The speedier-than-usual attack of "Ich will be meinem Jesu" [CD.1 tr.20] is to be contrasted with the similarly unexpectedly slower "Wer hat dich so geschlagen" [CD.1 tr.37]. In none of these cases is the deviation gratuitous. There is a dramatic – and so implicitly confessional – rationale: the events of the first Easter are of great moment. Our reactions as onlookers (if necessarily not participants) are at best febrile; surely fervent; possibly ones of panic. This is what Jacobs' forces suggest. This emphasis on contrast and drama (the relative ranking of Choir 1 over Choir 2, for instance) confers a subdued yet sensuous tone to the performance.

On the third count Jacobs enters with what seems like unassailable logic the fraught field of those directors/conductors aiming to arrive at an authentic performance. Chief among components of this aspect of authenticity is the size of the forces used in 1736 specifically; and in Bach's lifetime more generally. The then sexton of the Thomaskirche reported that "both" organs were used. The thesis that the second organ was in the swallow's gallery in front of the Triumphal Arch (above the passage from nave to choir) has traditionally been discounted because it was assumed that the space was too small to accommodate the number of performers needed. But that would be the case only if that number was larger than many experts (of the one-to-a-part camp) now believe. Jacobs' conception is of an almost Venetian disposition of cori spezzati, but situated along the east-west axis of the church, rather than side to side. This works well when implemented for this recording. Though it may take some getting used to; and is perhaps best experienced in Surround Sound.

The Thomaskirche is a long and relatively narrow building and its somewhat dry acoustic allows more impact this way – especially in those few almost unbearably climactic moments when the story of the Passion seems to turn on the purity of choral dialog. This is not a trivial point: if Jacobs' logic is followed and accepted, it's necessary to accept that Bach intended a much more disputatious story to be told where the heads (or at least the ears, minds) of the congregation were assailed by positions literally diametrically opposed to each other. Various analogs spring to mind: the crucifixion as act of cruelty and salvation; the ensuing outcomes of the "Sünde groß" as also positive; the legitimacy or otherwise of the positions of the participants in the "trial"; the relationship between Christ and God; forgiveness and persecution; above all, the isolation of Christ in the midst of onlookers, family and antagonists.

Almost imperceptibly, certainly without any self-consciousness, Jacobs has set out to answer one question, to confront one conundrum, about the precise location of the German Passion at a time when its status was – at the very least – in flux: how can an audience of the twenty-first century understand the tension between Biblical epic and the inexorable elevation of the dramatic in music? Jacobs' answer here is to create and then rely on an informed and wholly justified warmth in performance that must parallel Bach's unshakeable faith and believe in his own abilities to express it by marrying a hugely varied range of musical strengths with Picander's text. The self-conscious, self-doubting, world of Beethoven, Mozart even, scarcely two generations later, can hardly be imagined from the subdued lyricism as tempered by single-minded enthusiasm of the recitatives – listen, for instance, to the earnestness of the way in which Pilate, Pilate's wife and both choruses "bargain" over whom to release [CD.2 tr.8], for example. Jacobs draws us in completely.

The performance on two CDs splits at "Wer hat dich so geschlagen", nearly 15 minutes into the second part of the Passion. The soloists (both vocal and instrumental) do Jacobs proud. Bernarda Fink's mezzo and Konstantin Wolff's baritone as well as Werner Güra's commanding Evangelist are particularly notable. So too are the Berlin RIAS Chamber Chorus and Academy for Ancient Music Berlin. They are entirely invested in the performance from start to finish. And, although this is not a Matthew Passion that is likely to leave you speechless or in tears at the end (it has a more practical, "functional", air than that), you'll need to be handy with your CD player's "Stop" or "Pause" button if you don't want to hear the two Anhang (addendum) movements, "Ja, freilich" and "Komm, Süßes Kreuz" after the final chorus not quite at the end of the second CD. Perhaps these would have been better placed at the start.

The acoustic of the CD version (reviewed here) prizes realism over spectacle and effect. This is all to the good. At the same time there are moments such as in the aria, Blute nur [CD.1 tr.8] and the choral portions of "Ach, nun ist mein Jesus hin" [CD.1 tr.30] when the feel of the locale with its perceptible resonance strikes the listener as much as the words, perhaps. By and large we are happily lost in a performance that may evoke the "event" for which the Passion was first written – a Good Friday gathering of worshippers who were at first shocked by the profundity of what they heard; but soon surrendered to the emotions it evoked.

What's more, Jacobs and his engineers never falter in musical balance. On the contrary, their unusually-oriented (front-rear) panorama benefits our sense of impending tragedy. Particularly notable is the fact that the efforts of both individual instruments and soloists can all be heard with perfect ease: close miking of the strings, for instance, gives a chamber music quality to the playing; and every syllable of the soloists is enunciated with great clarity.

The lengthy and substantial booklet that comes with the two CDs contains background to the ideation of this Matthew Passion – particularly in terms of the disposition of choirs and soloists (members of the choirs: Bach was always lamenting his lack of resources); notes on the performance itself; some reflections by Jacobs as well as brief biographies and photographs of the performers and performance; and the full text in German, French and English. Although the material dealing with the musicological rationale behind this conception could have been slightly better organized, there's enough solid reasoning to allow even those unfamiliar with the lengthy debate about how Bach worked in general, and how he managed his performers for these occasions in particular, to understand how and why what they're listening to works in the ways that it does. Listeners would be well-advised to read these essays – especially if already familiar with the Matthew Passion: they explain the specifics of instrumentation and "staging" necessary to understand this interpretation. In any case, Jacobs' conception and execution are immediate, striking, likely to please most listeners, stimulating, technically exciting, perceptive and penetrating. In a word, hugely successful.

No matter how many versions of this work you have and listen to, there always seems room for one more. That's certainly the case here. Like some of René Jacobs' other recordings, this Matthew Passion doesn't exude Baroque sensibilities. It's very much a modern interpretation (one is almost tempted to say, "recreation") of the work. But such a rethink is never either gratuitous or lacking in purpose. the high points are all there – "Erbarme Dich" the [CD.2 tr.2] is as poignant (though never approaches the maudlin) as it must be, for example. The final chorus (indeed each of the major choruses) is infused with a simple small-spectrum and reduced color-range light that somehow penetrates to the very essence of what Bach intended. As is often said of Historically Informed Performance, it's at its strongest by being what is produced properly in our own times. You need be in no doubt that Jacobs is capable and convinced of that approach. Here he has achieved as much polish as passion.

Copyright © 2014, Mark Sealey