The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Blacher Reviews

Brahms Reviews

Mozart Reviews

Stravinsky Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

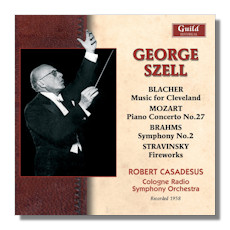

George Szell in Cologne

- Boris Blacher: Music for Cleveland

- Wolfgang Mozart: Piano Concerto #27 *

- Johannes Brahms: Symphony #2

- Igor Stravinsky: Fireworks

* Robert Casadesus, piano

Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra/George Szell

1958 Broadcast

Guild GHCD2404 77:53

For an artist of his fame and stature, George Szell guest conducted with relative infrequency. This was no doubt because he had an ensemble in Cleveland over which he had total control, and his artistic vision was almost always realized as a result. As a guest conductor he had less control in theory, although his abilities to change an orchestral sound are well documented, both in the notes to this release and elsewhere. This Guild release from 2013 preserves a 1958 concert in Cologne, and proves valuable on multiple levels.

The concert is bookended by two composers not generally associated with the Maestro, namely Blacher and Stravinsky. The latter was programmed little by Szell, but recorded evidence proves it could be a wholly successful collaboration. And so it proves. As for the Blacher, this short work was written especially for Szell and his Cleveland players. It's totally outside of what we normally would think of as Szell's territory, with abrasive and gnarled sounds in what amounts to a massive virtuoso display packed into just over eight minutes. Even more impressive is that the conductor gets such results out of his Cologne forces, Blacher asks for a lot, and Szell secures it.

Moving on, the Concerto #27, Mozart's last, certainly qualifies as Szell territory. His preferred soloist for this music was on hand for the occasion, and Casadesus upholds his reputation here as a marvelous Mozart player. For his part, Szell provides his customary backdrop, incisive and classically poised in the outer movements, and ideally balanced in the Larghetto. The Cologne forces prove inferior to Szell's Clevelanders, but not terribly so. Winds are perky, strings attack forcefully in the conductor's customary fashion, and while Szell never asked for "pretty" Mozart, doubtless he would have preferred a little more tonal warmth. Happily, the pianist matches the chamber-like approach with typical elegance and grace. I do believe this is my first recording of Casadesus that is my own, and there is no question that he fits Szell's vision of Mozart exceptionally well.

Brahms' Symphony #2 was one of the highpoints of the conductor's classic Columbia cycle, and he always did the piece well. As with many of his European efforts on behalf of the composer, I find that the slight decrease in ensemble quality is compensated by a new dimension of warmth and rhythmic freedom. The Cologne forces again play as well as they can, following Szell's every direction with commitment and clarity. The winds remain slightly acidic in tone, the strings a touch steely, but overall the results are quite fine. Szell commands respect for his ability to take a second-tier ensemble and produce Brahms that compares favorably to his efforts in Cleveland. Finally, the Stravinsky ends the program as an encore of sorts.

The sound is a typically decent late-fifties broadcast that faithfully conveys the strengths and weaknesses of the orchestra. Casadesus tone and instrument are not especially flattered, but it doesn't matter much; that's still the best item on the program. Full Szell concerts are rare, but nearly all of them are excellent, and every one tells us something about the conductor regardless of how familiar the repertoire may be. This is no exception. A valuable release.

Copyright © 2014, Brian Wigman