The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

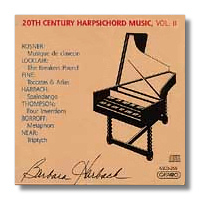

20th Century Harpsichord Music

Volume II

- Arnold Rosner: Musique de clavecin, Op. 61

- Dan Locklair: The Breakers Pound

- Vivian Fine: Toccatas and Arias

- Barbara Harbach: Spaindango

- Randall Thompson: 4 Inventions

- Edith Borroff: Metaphors

- Gerald Near: Triptych

Barbara Harbach, harpsichord

Gasparo GSCD-266 70:53

Summary for the Busy Executive: A grab-bag of work in good performances.

Probably Wanda Landowska, as much as anyone, revived the harpsichord as a contemporary instrument. Fairly prominent musicians had dismissed the harpsichord. See Beecham's notorious remark about the sound reminding him of cats copulating on a tin roof. Vaughan Williams, a composer who revered Bach and conducted him with deep psychological insight, always used piano as part of the continuo. Indeed, he remarked that he would not have a harpsichord in the same room as any concert he conducted. Landowska, who regularly gets rapped for her lack of "authenticity" and her ignorance of Baroque performance practice (compared to an undergraduate music-history major today), nevertheless brought the harpsichord back into notice both with highly imaginative – even extravagant – readings of Baroque and Classical masterpieces and with commissions of great modern works, notably by Falla and Poulenc. She helped bring the harpsichord into the notice not only of the public, but of the composer. Largely due to her although not written for her, we now have masterpieces by Barta, Stravinsky, Carter, Frank Martin, and Martinů, among many.

As in most collections, I enjoy some works more than others. For me, the real standout is Rosner's Musique de clavecin. Rosner studied with avant-gardistes, including Lejaren Hiller and Henri Pousseur, but his music owes almost nothing to them. It stands firmly in the neoclassic Modern camp, of the kind practiced from the Thirties through the Forties. His music has far more in common with Bloch, Hovhaness, Hindemith, and Vaughan Williams than it does with the antics after World War II. Rosner is a born composer, having written mature string quartets at an early age, but he is also a great artisan. His works show both architectural brilliance and emotional depth. Like most of our neoclassicists, however, Rosner's structural vigor disciplines a Romantic sensibility. Musique de clavecin paints the portraits of women Rosner knew in the Seventies, and the composer explicitly links it to Couperin's descriptive keyboard pieces. Although, the piece lacks a specific program, it doesn't really need one; it works just fine as "pure" music. From a technical viewpoint, I was struck by how Rosner builds crescendo and diminuendo into the piece (he also specifies a harpsichord with a 16-foot stop, which adds a strong foundation to the tone, as well as provides more volume). Neither articulation is "natural" to the instrument, which is why most composers resort to "terraced" dynamics when they write for harpsichord – sharp, high contrast of dynamic levels, rather than smooth builds. Rosner also builds terraces, but he nevertheless creates the illusion of gradual increase and decrease as well, usually by a canny gradual thickening or thinning of the chordal texture – ie, more or fewer notes in the chord. A keyboard dance suite could amount to little more than a throwaway, but Rosner strives for Couperin or even Bach, at least in the final, passacaglia movement – an adagio that amasses great power as it goes along and thus lends weight to its sibling movements. The sections differ from one another in character – from light dance to threnody – so the suite leads you through a great emotional range. I've raved over Rosner several times in these reviews. I'm a fan. For me, he is a master.

I've heard some of Dan Locklair's output, mainly organ preludes and scores for wind ensemble, which I find well-written and even poetic, but I can't claim to know him in depth. It's been hit-and-miss, blind luck that I've heard some pieces and not others. The Breakers Pound is yet another dance suite. It shows some unusual features: older forms like pavane and galliard mix with waltz and rag (a particularly woebegone rag, unfortunately), for example. But it's not really up to Locklair's best. Furthermore, as light music, pleasant enough, it lacks sufficient attraction and especially harmonic variety to make you want to hear it more than once.

Vivian Fine's Toccatas and Arias suffers from exactly the opposite problem. It's a Serious Piece, way too serious for its own good. In its way, it bores just as much as the Locklair. It lacks any strong direction. Fine, a pupil of Sessions, Cowell, and Ruth Crawford Seeger, has written with great craft, but little compulsion. I can admire its counterpoint and motific development, but I'm not really moved.

Edith Borroff's Metaphors is a serial piece – that is, it's based on a tone-row – but it's quite tonal and the "row" doesn't contain all the notes of the chromatic scale. It displays the same high-mindedness as the Fine, but it actually manages to go somewhere. The composer describes it as extended lyricism, which seems to me on the money. I love this work, full of a deep understanding of the instrument and how to surmount its limitations. A harpsichordist herself as well as a composer, Borroff has found imaginative ways around the harpsichord's tonal sameness. Like Rosner, she has discovered how to keep interest over the long span.

Randall Thompson's inventions belong to the larger collection, 20 Preludes, 4 Inventions, and a Fugue. Thompson began them as teaching pieces for his tonal counterpoint students at Harvard. He would compose on the spot, ask at various points along the way for suggestions, and then finish up. An assistant would transcribe the completed work. It takes a while for most people to compose even two measures of music, so these works are, necessarily, short. They also come out of practical, pedagogical circumstances. Don't expect something on the level of The Peaceable Kingdom or the Second Symphony. The inventions are firmly in the idiom of Bach and Handel keyboard works. However, their quality definitely wowed me. They are fully as good as some Bach and Handel, with surprising modulations, beautifully worked out in the Baroque idiom.

The two lollipops on the program – Gerald Near's Triptych and Harbach's own Spaindango – bring welcome leavening. Harbach Spaindango – described in the liner notes as a bolero rhythm, for some reason – is really a fandango or perhaps a sevilliana. It's vulgar, energetic, and fun, dancing with a metaphorical rose in its metaphorical teeth. The Near, in Debussy's words, "seeks humbly to please" and succeeds. It's not a world-beater, but it does have great charm.

Harbach does well by them all. My one quibble lies with the performance order of the Thompson inventions. I think she should have wound up with the sprightly second, rather than the subdued fourth. I doubt Thompson actually specified order. The recorded sound is fine, if not spectacular.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz