The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Article

Article

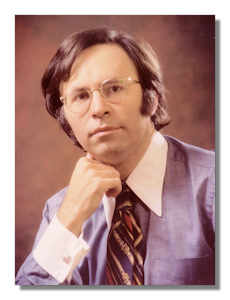

Anthony Newman

The High Priest of Bach is Still Controversial

by Dean Farwood

On February 15, 1967, Johann Sebastian Bach's organ works were brought back to life after nearly 220 years of mostly specious performances. That night, at the Carnegie recital hall, 26-year old Anthony Newman played Bach organ pieces on the pedal harpsichord and did so in a style that hadn't been heard since Bach's days.

Since the 1830s, Bach's organ works have generally been played slowly and with a rigid adherence to the metronome in a misplaced sign of respect for the great master of the Baroque. Newman, however, played the fast movements with fiery speed and all movements with elucidating rhythmic variations and improvised ornamentation – the same way the music was played in the 18th century, as Newman's research has demonstrated. The next morning, Howard Klein of the New York Times reported that Newman's "…driving rhythms and formidable technical mastery…excited the kind of clamor that is stirred by extraordinary artistry." Based solely on the Times' review, without an audition, Columbia Records signed Newman to a contract. Rather than market Newman as a young music scholar who played brilliantly, Clive Davis, head of Columbia, cast him as the hippy from Los Angeles who blew the socks off of the stuffy old classical snobs. Rolling Stone, in one of its first reviews of classical music, treated Newman as one of their own. They played up his interest in Zen and meditation and, in the vernacular of the 1960s, gushed "The music's a trip. Like it pulls strands of your mind out of their corners and ties them in loops and bows."

Newman's first album, Anthony Newman Plays J.S. Bach on Pedal Harpsichord and Organ (1969), was stunning. It brought forth the original energy of the music through brilliant tempos, rhythmic fluidity and improvised ornamentation and cadenzas. It won him many younger listeners; Newman's early concerts were unique for the number of young people in jeans and long hair coming to hear Bach. Time Magazine called Newman the "high priest of the harpsichord" – this praise would be echoed thirty years later when Wynton Marsalis dubbed Newman the "high priest of Bach."

For over forty years, some of the most exciting recordings of J.S. Bach's keyboard music have been made by Newman. With speed, accuracy, power and intelligence he has enlivened Bach's works by reviving the Baroque manner of playing - a collaboration between composer and performer. And, even though his career broadened to include conducting, composing, writing, and teaching, he is still dogged by the controversy that began even before his breakthrough recording for Columbia Records in 1969.

If the harpsichord and organ bring up unpleasant associations of prancing French ladies and gentleman in powdered wigs, church, or Lurch, please let these associations rest a moment. Harpsichords are, of course, stringed instruments. When the keys are pressed on the keyboard, plectra, similar to guitar picks, pluck the strings. Interestingly, when the key is released the plectrum passes across the string again making a sound that is usually covered by the other notes. A pedal harpsichord has the typical multiple keyboards but, in addition, has an array of long, thicker bass strings connected to organ-like pedals that produce rich, resounding and very potent bass lines with the impact, at least when Newman plays, of thunder.

Newman is equally at home playing pipe organs, odd instruments with huge sets of whistles that can be configured to mimic the overtone structure of instruments like flutes, violins, clarinets, and bassoons but can also produce sounds that are unique to the organ. Because they are not portable and are usually found in public spaces like churches, it's difficult to find a time to practice (in the Baroque period pedal harpsichords were used for organ practice at home). When they are found in private settings, pipe organs usually appear in the nightmarish basements of brilliant but evil cinema villains.

But the worst nightmare of the organ, according to Newman, is that it's usually played legato – one note persists until the next note begins leaving no space between notes. Baroque organ music played this way becomes muddled; it's hard to believe that Bach, with his mastery of independent, simultaneous melodies, would play notes through to their written values, thus obscuring the counterpoint. "Playing notes to their full value is the curse of the organ; it's what drives people out of the room," says Newman. When Bach is played with clean articulation and exciting tempos giving clarity to the structure of the composition, as Newman does, the music welcomes and rewards the listener. If you think that you don't like the organ or Bach's music, then you should not miss an opportunity to hear a Newman organ recital in a hall or church with good acoustics. It may not pull out strands of your mind but it will allow you one of the most immersive experiences of beauty in your life. But don't wait; Newman, while still vigorous (at 70 he swims, runs and meditates daily), now gives fewer than 25 concerts a year.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, musical pedants required that Bach be played slowly. This was deemed to show the proper respect for the complex music and the composer who had now been put on a pedestal. This overly reverential style of performance persists to this day. Newman compares this misplaced respect to a performance of Shakespeare. Great as Shakespeare was, "you wouldn't say his lines with respect; you'd say them with passion."

According to Newman, many of the performances of Bach that we hear today on modern instruments follow neither the performance practices of the 18th century nor, with a few exceptions such as the uninformed but brilliant work of performers like Jascha Heifetz and Vladimir Horowitz, the spirit of the Baroque. In 1985, Newman published Bach and the Baroque (Pendragon Press Musicological Series), in which he made an extremely strong case for his own fast-paced, ornamented and driving performances of Bach's music based on his study of the writings of Bach-era composers such as Mattheson and Quantz, Bach's student Kirnberger, Bach's sons (who were also composers), and others. Examination of Bach's students' copies of his works show frequent ornamentation not found on Bach's original scores. The bottom line: Bach's pieces were played faster than they are today and scores were not followed rigidly – improvisation, ornamentation, and changes of tempo to highlight the music's inner structures were common and recommended.

It is worth exploring the differences; visit YouTube and listen to a traditional organ version of Bach's C minor Fantasy and Fugue, BWV 537 (by Bernard Foccroulle). It will take just over nine minutes to get through the whole thing, one-third longer than Newman's version. It's hard to imagine Bach playing it so slowly and so lacking in expression. Try to listen to the whole piece but, if you can't stick it out, drag the play indicator (using the timer as a guide) to 5:18. Brace yourself for the tedium of misguided respect as the laboriously slow fugue begins.

Now listen to Newman's pedal harpsichord version from his first album (disgracefully out of print). Notice how he adds double-dotting (instead of even, legato notes – DaaaDaaaDaaa – he plays Daaa – TA-Daaa – TA-Daaa), a style which funnels more power to the downbeats, and was a common technique in the Baroque period. There are also changes in tempo, an example of which is found at 1:13 – 1:15. Listen at 2:12 where Newman uses the sound of the plectra passing back over the strings as a percussive accent. There are wonderful trills and other ornamentation not found in the previous, sterile version. Compare his Fugue which starts at 3:35 to the one previously mentioned.

Back in the 1970s, Newman offended the gang of traditionalists who disdained his fast tempos, rhythmic alterations and added ornamentation. Ironically, the "tradition" preserved by these conservatives is one that began long after Bach's death. They have never questioned Newman's virtuosity; he plays fast and clean, with a clear, overarching scheme for each piece. But his Bach is too flashy for them. This too is ironic because, when playing, Newman displays none of the physical mannerisms of the Romantic period from whence Bach reverence and restrictions were born. Many of the old guard emote with head bobs, trunk circles, see-sawing wrists and pained expressions. Newman sits relaxed and quiet as he plays without affectation.

Critics have been of two minds about Newman's "singular approach." The New York Times has vacillated:

"His driving rhythms and formidable technical mastery…and his intellectually cool understanding of structures moved his audience to cheers at the endings." (1967)

"A hiccup effect, or a sudden pause…is it rubato or something else that Mr. Newman applies…whatever it is, it lurches absurdly." (1969)

"His use of rubato as a structural device is particularly subtle – tiny pauses at various key spots to isolate and define vertical blocks within a phrase" (1976)

"…his accents…startle, even outrage…it is like listening to someone who speaks your native language with breathtaking fluency but in a thick accent, sprinkled with outrageous mispronunciations." (1976)

"His free use of rhythm to define larger phrase structures…does serve its purpose admirably in addition to adding a touch of drama to his performances." (1979)

The importance of music critics, however, has declined with the development of the Internet. With online resources like Rhapsody, YouTube, and iTunes, we can decide what we like for ourselves. We can compare for example, Newman's casual recording (left), at age 69, of Bach's G minor Fugue, BWV 542, with a well-produced but very staid traditional version by Hans Andre Stamm (right).

Newman has also composed a significant amount of music – as much as Stravinsky – and has just released his most important compositions in a 20CD set. His music is essentially tonal and employs archetypes from early 20th century composers like Stravinsky and Bartók, as well as constructions from the Baroque and Classical periods, resulting in music that often has the same powerful and touching effect as music of the past. A few of his many compositions well worth hearing include:

- 12 Preludes and Fugues for piano – fascinating pieces and which, similar to Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier (WTC), are in ascending key order. These pieces, like Bach's WTC would be well worth an advanced pianist's time to master (1990)

Two neoclassical orchestral symphonies (1998)

A Requiem for chorus and orchestra (2000)

A stunning Theme and Variations for flute quartet (2004)

Based on the Planets for cello and piano with an eerily perfect movement named Venus which simultaneously evokes large distances and intimacy (2006)

Based on the Elements, a piano sonata in four movements: Water, Earth, Air and Fire (2007) and,

A Sonata for violin and piano (2010)

Despite his prodigious body of work and the fact that he has been composing since the 1970s, he is just beginning to be recognized as a composer.

Newman is a composer, conductor, writer and teacher but it is his performance of Bach that makes him an American master albeit, since the 1970s, largely underappreciated. The reason that Newman's powerful and expressive Bach has not been received into the mainstream of the classical music world is, according to Newman, simple: people are accustomed to hearing music a certain way and become biased. Today, over 40 years after his debut album, Newman is still an outsider in the world of Baroque organists and harpsichordists. Despite, or perhaps because of, his recording and concert success during the 1970s, award-winning recordings of Beethoven Piano Concerti in the 1980s, his arrangement and conducting of the biggest selling classical album of 1996, Wynton Marsalis' In Gabriel's Garden (it was he who wrote out Marsalis' trumpet ornaments - Sony SK66244), and 27 consecutive composer's awards from ASCAP, the large conservative wing of the self-referential Baroque keyboard club consider Newman unworthy of notice. He was twice named Harpsichordist of the Year and once Classical Keyboardist of the year by Keyboard magazine yet chairs of harpsichord and organ departments at a number of American music conservatories are generally unwilling to discuss his work. Perhaps Newman is right; it could be that unfamiliarity breeds contempt. Thus, Baroque harpsichordists and organists, who are often highly educated in their field and are capable of verifying Newman's research on Baroque performance practices, are tainted by an inbred conviction that Bach can only be exciting to musical intellectuals who are uniquely capable of appreciating Bach's contrapuntal refinements. To them playing Bach passionately is just too carnal.

Copyright © 2011, Dean Farwood.

Select Discography - As Performer

J.S. Bach

|

J.S. Bach

|

J.S. Bach

|

J.S. Bach

|

Bach at Lejansk

|

J.S. Bach

|

Beethoven

Newport NCD60031 |

Beethoven

Newport NCD60081 |

Beethoven

Newport NCD60007 |

Beethoven

Newport NCD60027 |

Beethoven

|

Beethoven

Newport NCD60097 |

As Composer

New Music

Margaret Mills, piano Flute Force Laurentian String Quartet Newport NCD60032 |

On Fallen Heroes

Christopher Lewis, piano John Dexter, viola New York Arts Orchestra/Anthony Newman Newport NCD60140 |