The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Addison Reviews

Arnold Reviews

Bliss Reviews

Rubbra Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

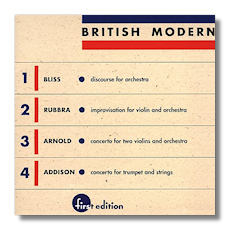

British Modern, Volume 1

Orchestral Works

- Arthur Bliss: Discourse for Orchestra (1957)

- Edmund Rubbra: Improvisation for Violin & Orchestra, Op. 89 (1955)

- Malcolm Arnold: Concerto for 2 Violins & String Orchestra (1962) *

- John Mervin Addison: Concerto for Trumpet, Strings & Percussion (1958) *

Sidney Harth, violin

Paul Kling & Peter McHugh, violins

Leon Rapier, trumpet

The Louisville Orchestra/Robert Whitneyr

* The Louisville Orchestra/Jorge Mester

First Edition FECD-1904 Mono/Stereo 67:36

Summary for the Busy Executive: Welcome back.

In the Fifties and Sixties, the Louisville Orchestra, under the guidance of its director Robert Whitney and with the support of the Ford Foundation, embarked on one of the most enterprising commissioning and recording series of its time. Whitney had wide-ranging interests. Although he concentrated on American composers, he did not confine himself to them. Like most talented commissioners, he seemed to know whom to ask for work. Louisville premièred live performances or recordings of scores by Martinů, Milhaud, Hindemith, Bloch, Ibert, Foss, Hovhaness, Chou Wen-Chung, Riegger, Sessions, Mennin, and Piston, among many others.

First Editions has repackaged many of the original recordings, and, thank goodness, in a rational way. Here we have a selection of work by British composers. The Bliss and the Rubbra were Louisville commissions. All four recordings were premières. The Louisville First Edition series constituted an important part of my musical education 'way back when – an easy, mostly painless introduction to 20th-century music. Whitney, a Britisher himself, knew the English scene quite well and could dig a bit deeper to find more than the usual suspects.

Sir Arthur Bliss made his biggest splash in the Twenties and Thirties as an aggressive British Modernist, aligning himself with Stravinsky and the younger French. His Modernism, however, turned out mostly superficial – a matter of concept, really – and his links to Elgar and late Romanticism soon became apparent. In the Thirties, he was eclipsed by Vaughan Williams and Walton, in the Fifties by Britten. However, he succeeded Bax as Master of the Queen's Music, and his postwar music, with the exception of his oratorio Morning Heroes (a work that comes out of his experience of the First World War), remains the period of his work that interests me most. Discourse belongs to this period. Despite his Romantic language, I find a strongly objective, "illustrative" quality to his music. The music may build powerful climaxes, but this does not usually indicate any sort of personal catharsis. It's as if he observes emotions at a remove, rather than feels them himself. I don't condemn, I merely describe the peculiar atmosphere of his music. For this reason, I think, some of his most successful work he wrote for ballets and film scores. Usually, these genres attract composers weak in structure, but that's certainly not the case with Bliss. Indeed, most of his music shows a strong architectural interest, and even playfulness. One sees this in the Discourse, which combines features of a variation set with a symphonic movement. Bliss later revised the score, not necessarily for the better (he cut out my favorite section), and this is the original version. It's a score of great color and energy, but not necessarily of great depth.

Edmund Rubbra has an artistic personality almost the exact opposite of Bliss' – sober, serious, and introspective. Rubbra studied with Holst and through him became enamored of the counterpoint of the Tudor composers, which he has applied to modern classical forms. He's a terrific symphonist, not all that interested in theater, and his music characteristically meditates, rather than sings or dances in the usual way, although it has both beauty and rhythmic interest. Much of the time it unfolds like an Elizabethan fantasia. The Improvisation for violin and orchestra, one of his finest scores, typifies his output. It proceeds in long, lyrical lines – although the composer may not have conceived it that way. For the lines consist of little bits of ideas, which Rubbra combines and recombines into new long melodies. Unlike many other composers who work in this fashion, Rubbra never leaves you in doubt as to where you are. Indeed, the effect of the score is that of a long melody played under different moods. The effect, in a good performance, is one of spontaneous inspiration. The score, however, shows the amount of work that went into achieving that effect.

Malcolm Arnold began his career as an orchestral trumpet player and virtuoso. His scores brim with the kind of practical, professional knowledge that players love. However, this quality sometimes got in the way of critics, who used to attack him as slick. His considerable income as a film composer didn't help. Musically, Arnold belongs to the Walton wing of British music. Unlike Walton, however, he feels the influence of Mahler, especially drawn to the inclusion of "low" elements in serious contexts. Early on, critics and audiences alike felt disoriented and put off, just as their counterparts had with Mahler. This also contributed to the low level of Arnold's stock and the undervaluing of many of his scores. With the appearance, however, of the seventh symphony, this assessment has been revised upwards.

Arnold has written at least twenty concerti, many of them for his friends or for players he admired. The concerto for two violins, commissioned by Menuhin, stands as one of his best. Although it lacks the composer's characteristic vulgarity and raucous humor, it compensates by a beautifully tight argument, contrapuntally advanced. Arnold wrote it in memory of his two brothers, which accounts for its sober (though neither stolid nor pompous) tone. It's so well-written that it brings to mind the Bach d-minor for two violins. The violins weave in and out in quasi-fugato and stretto. The accompanying strings provide lean, muscular support. The slow movement crowns the work: an intense, long-lined aria based on two related ideas, so that it becomes nearly monothematic. One point of interest: the finale is a rhythmic rewrite of the opening movement.

Like Malcolm Arnold, John Addison studied with Gordon Jacob at the Royal College of Music. After making a splash in the early Fifties with such scores as his ballet Carte Blanche, he became increasingly involved with theater and film. He scored John Osborne's Luther and The Entertainer and won the Academy Award for his music for Tom Jones. In the Seventies, he disappeared into movie and TV work in Los Angeles, coming up with the main title for, among other things, Murder, She Wrote. I wouldn't hold it against him. All the concert work by Addison I've heard has run on the light side, not excepting the trumpet concerto. He reminds me more of a French composer like Ibert or Françaix, full of blithe spirits, than the Modern British. The concerto, a masterpiece of light music, allows the trumpet to saunter down the boulevards, like Charles Trenet. It's more important than profound: it's loveable.

Paul Kling and Peter McHugh give a stirring performance of the Arnold, while Harth sings with warmth and intelligence in the Rubbra. Trumpeter Leon Rapier is appropriately cheeky in Addison's concerto. The Louisville never was a first-rank orchestra, but it worked heroically on behalf of, by definition, unfamiliar scores. The sound isn't super-swell, but it is acceptable. For those who care, the Rubbra and the Bliss are in mono. However, I believe only the Arnold and the Rubbra are currently available in modern sound. Even so, this remains a classic set of recordings.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz