The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- J.S. Bach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

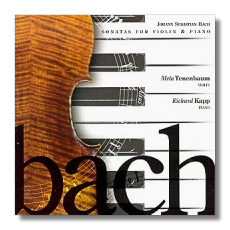

Johann Sebastian Bach

Sonatas for Violin and Keyboard

- Sonata #1 in A Major, BWV 1014

- Sonata #2 in A Major, BWV 1015

- Sonata #3 in E Major, BWV 1016

- Sonata #4 in C minor, BWV 1017

- Sonata #5 in F minor, BWV 1018

- Sonata #6 in G Major, BWV 1019

Mela Tenenbaum, violin

Richard Kapp, piano

ESS.A.Y CD1066/67 38:43 + 44:57 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Bach with an edge.

This set also comes in a violin-harpsichord version (ESS.A.Y CD 1064/65), with keyboardist Gerald Ranck. If you buy the piano set, you can get the harpsichord set for an additional $8.00 by filling out a form provided with the album. The liner notes, by Kevin Bazzana, indicate that Tenenbaum performs on a different violin as well and that one gets the opportunity to hear how differences in the instrumental forces lead to differences in interpretation a position I should not have thought controversial.

Bazzano, however, makes a great point right away: "With apologies to the National Rifle Association: instruments don't play music; people do." The fetishist weed of the HIP (historically-informed performance) movement regarding "authentic" instruments as the single path to glory, to the extent that it has risen, needs a thorough rooting. To my mind, you judge a result, and the preliminaries only in light of the result. I've seen great cooks make bizarre ingredients yield fabulous dishes. Similarly, I've heard great Bach on piano and on harpsichord, on modern violins and on instruments built according to Baroque principles. In each case, a great musician commanded the instrument.

I admire Mela Tenenbaum's playing enormously and thinks she deserves wider recognition. I've reviewed her recording of Bach's solo violin partitas and sonatas (ESS.A.Y CD 1049-50-51) and concluded that, within the context of the Russian school of violin playing, she had acquitted herself well, even against the file of great names like Milstein, Heifetz, and so on. No single musician pronounces the final word on Bach. You savor the individuality of a good interpretation.

Such a proposition holds true not only for a cultural monumenlike the solo sonatas and partitas, but also for the more "sociable" accompanied sonatas. Here, however, we must take care not to undervalue the accompanied sonatas. Bach characteristically put tremendous craft into just about everything he wrote. Even "routine" Bach probably stands head and shoulders above the best nearly everybody else, and, to that extent, Bach is both the idol and the despair of so many composers. The third movement of BWV 1015, for example, which (if you don't pay close attention) sounds like a typical 18th-century slow aria, actually proceeds as a strict canon between the violin and the keyboard's upper line, and almost every movement in the series bristles with "invertible" counterpoint (where the upper line gets music originally assigned to the lower line, and vice versa), stretto (where one voice takes up a line before another finishes), fugato a full contrapuntal toolkit, in short mainstays of Bach's practice. Counterpoint alone, however, doesn't make a great piece. Bach invents new turns, elevates and extends the expressive power of standard forms, and creates a musical poetry that speaks to the body, the heart, and the mind all at once all without the apparent self-consciousness of composers from Beethoven on (Schiller's "naïve" vs. "sentimental" artist). Bach, like Shakespeare, apparently "just writes," and everything falls into place within a complex whole.

The usual resort to contrapuntal building an extreme independence of each line implies a balance between the players other than the usual violin discreetly "supported" by the keyboard. Violin, keyboard left hand, and keyboard right hand work really as equals. The violinist can't treat these sonatas as Locatellian tours de force. The keyboardist must also command attention. Indeed, violinist and keyboard player must learn an intricate dance in which one gets out of the other's way. In Bach's music, this kind of switching occurs frequently. Kapp and Tenenbaum occasionally run into trouble (as in the second adagio of the fifth sonata), with Tenenbaum too aggressive and Kapp too shy, but it's a rare occasion.

Tenenbaum knows this music inside-out. Her performance shows a fresh thinking-through of every movement. You may not agree with what she comes up with in each case, but, if you know these works at all, you'll find yourself comparing her interpretations in detail with other violinists'. I compared her to Buswell (with Valenti, harpsichord) and Ritchie (with Wright, harpsichord). Buswell plays the sonatas as close to dances as possible, and I admit my sympathy with this approach, just as I prefer Italianate, as opposed to Germanic, performances of the cantatas. Ritchie, dean of Baroque fiddle technique, takes a relatively sober approach, unfortunately, not really what the music needs. To me, Bach's music tends to heaviness as one of its traps. It's not all that much of a stretch to give a sober, lugubrious performance not that Ritchie's performance plods. In fact, it's a very lyrical reading, full of chiaroscuro. However, I want more pep, more kicking up of the heels.

Tenenbaum has vim and vigor to burn. The quick movements suit her, and she eagerly leaps into a phrase as if she can't wait to get to the next. Listeners will, I suspect, find her slow, singing movements more controversial, however. She sings, but not necessarily sweetly. An uneasy current of nervous intensity marks her adagios and largos. There is a slowing down, but neither respite nor repose. Her playing in that regard reminds me a bit of the cellist Maisky both Byronic and, to some extent, extreme (Tenenbaum less than Maisky), in the sense of the phrase "extreme sports." These performances galvanize so, I found it hard to listen to more than two sonatas at a time. If one gulps down Buswell's readings like popovers or contemplates Arcadian visions with Ritchie, the listener hangs on for dear life in Tenenbaum's whirls (listen to the final "Presto" in the fourth sonata) and hold's one's breath waiting for Grendel to leap out and eat somebody in the slow movements. It's only a slight overstatement.

I happen to like these accounts very much. They are the products of an individual, mature, and strong musical mind, an antidote to the aesthetically safe and correct we get all too often. If I prefer her minor-key sonatas to her major-keys, it's because I think the temperament she reveals through her playing more serious than light-hearted. Nevertheless, it's a strong set, highlighted, for me, by the last three sonatas.

The performers seemed a bit too forward in the sound image. Sometimes, as in the third movement of the Sonata #6, for solo keyboard, I felt as if my head lay practically inside the instrument, but that's my only carp. Most of the time, the sound is fine.

Copyright © 1999, Steve Schwartz