The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

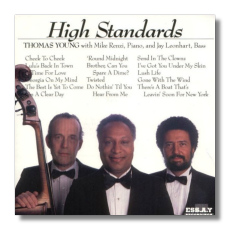

Thomas Young

High Standards

- Songs by Berlin, Warren, Mandel, Carmichael, Coleman, Lane, Monk, Gorney, Gray, Ellington, Sondheim, Porter, Strayhorn, Wrubel, Gershwin

Thomas Young, tenor

Mike Renzi, piano

Jay Leonhart, bass

ESS.A.Y. Recordings CD1025

Too often, "crossover" means crossing the tracks to a part of town you don't normally frequent. In effect, artists either pull long faces or affect a bonhomie that essentially apologizes for coming at all.

A certain lucky few don't cross over, because everything's in the neighborhood. Thomas Young belongs to this group. He seems able to sing anything. I've heard him sail through Bach arias, the most difficult modern operas, bel canto, show tunes, funk, and, here, jazz – a phenomenal set of pipes. He approaches my ideal of the American artist: one who not only understands our high and vernacular art but knows what we owe Europe as well.

The instrument is a major wonder. From the very first track – Berlin's "Cheek to Cheek" – we listen to a master vocalist. "Heaven, I'm in heaven," and Young takes off for the stratosphere to land securely on "speak," the height of the phrase, and a nightmare for singer wannabes like me. I've heard it forced, falsed, and faked. Young not only makes it, he gives you the impression that he could play with it any way he wanted. The closest reminder of this kind of technique is Sarah Vaughan. Berlin leads to Harry Warren's "Lulu's Back in Town," and Young shows that he swings, elegantly and effortlessly, ending up with a gorgeous scat line. A singer like Elly Ameling or Kiri Te Kanawa may know where the beat is, but for both, the beat is a precise instant in time. The attack is precise, but the line is cramped. For Young, the beat is a large room which his voice comfortably spreads around in. Yet, he doesn't simply wallow. His version of the bop standard "Twisted" crackles.

The danger of being able to sing anything is that you will, simply because you can. Vaughan herself was often guilty of this, and Young doesn't escape the charge either, usually in over-fussy ballads: "On a Clear Day," "Send in the Clowns," and the ending to "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime." On the other hand, he does a superb "Around Midnight" (with a searching, horn-like solo), and he can move almost imperceptibly from the verse's "free-form" to the chorus's slow lope in Ellington's "Do Nothing 'til You Hear from Me." His version of "Lush Life," one of the few, doesn't sink beneath the purple lyrics or the almost too-lush musical lines. The song as he sings it makes perfect sense, and his voice becomes a horn once again, even while he never loses the lyric. "Georgia on My Mind" stretches on virtuosically as Young bends the line this way and that, hairpin twists from jazz to funk to blues to, I swear, Fritz Wunderlich, and it works.

Despite the spotlight on the singer, this is no one-man marvel, but a tight collaboration. Renzi and Ray Brown disciple Leonhart give Young the solid structure he needs to play around in and the assurance they can go wherever he does. Renzi takes some very lovely solos as well ("Lush Life" is a standout).

The talent that never breaks through to general recognition is awesome. I don't know why any of these guys aren't better known (although they all get work). Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, one of the great technicians of his time, was flabbergasted by Aretha Franklin. You can go to school with Young as well.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz