The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Gibbons Reviews

Tomkins Reviews

Weelkes Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

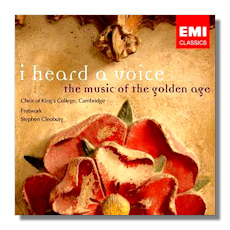

I Heard a Voice

The Music of the Golden Age

- Thomas Weelkes:

- Alleluia, I heard a voice

- When David heard

- Most mighty and all-knowing Lord

- Hosanna to the Son of David

- In Nomine I à 4

- Orlando Gibbons:

- Hosanna to the Son of David

- O Lord, in thy wrath

- This is the record of John

- O clap your hands

- In Nomine à 4

- Thomas Tomkins:

- O praise the Lord

- When David heard

- Fantasy à 6

- Rejoice, rejoice and sing

- O sing unto the Lord

Fretwork

Choir of King's College, Cambridge/Stephen Cleobury

EMI 394430 59:56

Summary for the Busy Executive: The King's College Choir with music, in some cases, made especially for them.

All three composers – Thomas Weelkes, Orlando Gibbons, and Thomas Tomkins – belong to the Tudor-Stuart era of British composition. In a sense, all are extremely conservative, particularly when you consider that Monteverdi and his Italian contemporaries are busy creating the Baroque style in the same period. The new-fangled stuff didn't really penetrate England until the end of the 1600s and the career of Henry Purcell, whose work put paid to the old modal, madrigalian idiom. Despite their different sensibilities, what unites Weelkes, Gibbons, and Tomkins is their concern for the meaning of the words they set.

Weelkes in his brief life (he died in his 40s, probably of alcoholism) achieved recognition as one of the best composers in a time of great ones. His achievement stands with Byrd, Wilbye, Morley, Taverner, Gibbons, and a slew of others. He excelled in compositions for many voices (his ayres, for example, are fairly weak and don't come up to Dowland's). He is a master of the expressive use of the "false relation" – often, the major and the minor third sounding simultaneously. In some cases, I believe, the differences of aesthetic expression between "then" and "now" force a listener to think himself into the earlier period. Composers like Byrd or Weelkes require less of that, due to their strong penchant for drama. The CD opens with Weelkes's "Alleluia, I heard a voice" – a blaze of choral fanfares as heaven and earth praise the Lord. The choir alternates with solo bass in an heroic, virtuosic part – maybe the finest single track on the disc. King's sings the bejeezus out of it. "Hosanna to the Son of David" gives us more of the same. "When David heard" sets David's lament for Absalom, probably the finest treatment of the text to this day. It sinks into grief. Its cross-relations become cries of pain. Powerful stuff.

"Most mighty and all-knowing Lord" is essentially a sacred "consort song": solo voice and viols, in a strophic setting of text. Not only does the vocal part stay the same, the viol parts do as well.

Orlando Gibbons, considered the finest keyboard player of his age, began his highly successful musical career as a chorister at King's, where his brother Edward led the choir. He became the senior organist of the Chapel Royal and held two other important musical posts at court. He died in his early 40s of a brain hemorrhage. Compared to Weelkes, Gibbons is suave, rather than dramatic, but he can certainly handle elaborate counterpoint and large forces, as shown by the ornate and high-spirited "O clap your hands" for 8 voices. The large number of parts provide not only volume but great textural variety of choral timbre and choral effects, like antiphony. Gibbons tends toward more simple tonality and more straightforward declamation than Weelkes. In "O Lord, in thy wrath," the polyphony cuts out for a single rhythm on the repetitions of "O save me" – the moral lesson of the passage. One can also hear anticipations of the Baroque occasionally peeping through, in a greater regularity of phrasing and a greater concern for specifying orchestration. "This is the record of John" shows Gibbons in a genre he mastered: the consort song with solo voice and chorus. Viols back a solo tenor who tells the story of the priests' messengers coming to John the Baptist and essentially asking for his bona fides. The tenor serves as the main narrator, and Gibbons takes great care to let the words shine out. This is, after all, religious instruction. The chorus repeats important passages (to different music). Overall, the piece impresses with the elegance of its layout.

Thomas Tomkins, born in southwest Wales, lived a life long enough (he died in his 80s) to see his style of music superseded. He was born during Elizabeth I's reign and almost made it to Charles II's. He may have studied with Thomas Morley and was a friend and colleague of Gibbons at the Chapel Royal. The Civil War and subsequent Commonwealth took his church living from him and he turned to keyboard and consort music. Musically, he has more in common with Weelkes than with Gibbons. His style was considered old-fashioned in his day and he himself a modest composer, despite his appointments. I like his music for its rough vigor, probably the very thing that made his contemporaries underestimate it.

"O praise the Lord," in 5 parts, shows Tomkins's ability to fill up a cathedral with sound and a sensitive ear for choral texture. "When David heard," to the same passage as the Weelkes, hasn't the psychological depth, rhythmic suppleness, or contrapuntal complexity of the latter, but it does speak more directly. The pain of David comes out mainly in the movement of the choir from low registers to high and back into the murk. The high notes become David's cries. Toward the end comes a remarkable imitative passage the encapsulates this strategy. At "Would God I had died for thee," the interval from "would" to "God" begins as a rising minor third. It immediately retreats to a rising semitone and then alternates between minor thirds and semitones for a bit. Finally, the minor third becomes a rising fourth, then a fifth, and finally a minor sixth, as the father keens for his son. "Rejoice, rejoice and sing" alternates soloists and full choir, much like "This is the record of John," as it depicts the angel Gabriel's annunciation to Mary. Compared to Gibbons, the choir becomes the main focus of music interest. The mix of imitative and declamatory passages is especially well laid-out. "O sing unto the Lord a new song," in 7 voices, strikes me as a little routine, until we get to the end and some wonderfully goofy alleluias – a syncopated riot of false relations.

Fretwork fills the disc with fantasies for viol consort. The two In nomines, by Weelkes and Gibbons, represent a subgenre of consort music that takes the chant "Gloria tibi trinitas" and uses the notes as the structural spine of the work. The chant sounds in long notes, while the other instruments weave florid counterpoint around it. Often the chant is in the bass, but in the pieces here it occurs in an inner part, so it gets buried to some extent and the counterpoint gets the most attention. [An interesting side note: Vaughan Williams uses a phrase from the chant in his Tallis Fantasia.] Weelkes wins the counterpoint honors hands down but doesn't seem to understand the difference between an instrumental and a vocal work with text. In the latter, the text phrases usually lead to the overall shape. In the instrumental, the composer must find a shape pretty much from the start. That's one reason why so many early examples of instrumentals are conventional dances: the forms are pre-tested, as it were. Gibbons pays more attention to this, although he doesn't use a dance form, more like a meta-madrigal. Tomkins's five fantasies for 6 parts includes some of his best music for consort (35 pieces in toto, mostly in 5 parts). The present work, far more extensive than the other two, bears comparison with examples from giants like Byrd and Gibbons. Again, the madrigal provides the basis of the design. As I listened, words from madrigals I knew fit the instrumental parts perfectly.

Let's face it. This is King's core repertoire. I don't know how others feel about it, but I think the choir's actually improved since the David Willcocks days, when it was merely the epicenter of English cathedral choral singing. On the other hand, I have heard other choirs do better, in Weelkes's "When David heard," especially. However, that may stem from my preference for adult to child trebles, whom I find – even when they're as superb as King's – lack flexibility and nuance. I'm very fond of Grayston Burgess and the Purcell Singers who put out an LP (naturally, never transferred to disc) of at least some of this music, accompanied by organ and brass. Their "Alleluia, I heard a voice" made you see heaven itself open up in glory. Nevertheless, this is one fine CD, significantly enhanced by the contributions of Fretwork.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz