The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

EMI Classics

double fforte Reissues

Dmitri Shostakovich

- Symphony #10 in E minor, Op. 93 (1953)

- Symphony #13 "Babi Yar" Op. 113 (1962)

Dimiter Petkov, bass

Men of the London Symphony Chorus

London Symphony Orchestra/André Previn

EMI Classics CDFB 73368 ADD/DDD 2CDs: 52:21, 62:43

Hector Berlioz

- "Symphonie Fantastique" Op. 14 (1828) *

- "Harold in Italy" for Viola & Orchestra, Op. 16 (1833) *

- Overture "Béatrice et Bénédict" (1862)

- Overture "Les Francs Juges" Op. 3 (1826)

- Overture "Le Carnaval Romain" Op. 9 (1844)

- Overture "La Corsaire" Op. 21 (1831)

- Overture "Benvenuto Cellini" Op. 23 (1838)

* Donald McInnes, viola

* Orchestre National de France/Leonard Bernstein

London Symphony Orchestra/André Previn

EMI Classics CDFB 73338 ADD 2CDs: 77:14, 66:20

Franz Schubert

- Symphony #1 in D Major D. 82 (1813)

- Symphony #2, D. 125 (1815)

- Symphony #3 in D Major, D. 200 (1815)

- Symphony #4 "Tragic" in C minor, D. 417 (1816)

- Symphony #5, D. 485 (1816)

- Symphony #6 in C Major, D. 589 (1818)

Menuhin Festival Orchestra/Yehudi Menuhin

EMI Classics CDFB 73359 ADD 2CDs: 78:36, 78:37

The Early BBC Recordings 1961-1965

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Cello Suites #1 & 2

- Benjamin Britten: Cello Sonata in C (2 mvmts)

- Manuel de Falla: Suite populaire espagñole

- Johannes Brahms: Cello Sonata #2

- François Couperin: Treizième Concert (Les Goûts-réunis)

- George Frideric Handel: Sonata in G minor

Jacqueline du Pré, cello

Stephen Kovacevich & Ernest Lush, piano

William Pleeth, cello

EMI Classics CDFB 73377 ADD 2CDs: 60:08, 52:17

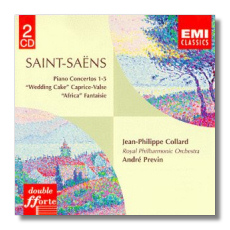

Camille Saint-Saëns

- Concerto #1 in D Major for Piano, Op. 17 (1858)

- Concerto #2 in G minor for Piano, Op. 22 (1868)

- Concerto #3 in E Flat Major for Piano, Op. 29 (1869)

- Concerto #4 in C minor for Piano, Op. 44 (1875)

- Concerto #5 "Egyptian" in F Major for Piano, Op. 103 (1896)

- Caprice Valse "Wedding Cake" in for Piano, Op. 76 (1886)

- Fantasy "Africa" in for Piano, Op. 89 (1891)

Jean-Philippe Collard, piano

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/André Previn

EMI Classics CDFB 73356 ADD 2CDs: 79:20, 77:29

EMI's double fforte series is a bargain for the discerning collector. Each release contains two discs for the price of one. Although the recordings come from the previous three decades, the digital remasterings make them very competitive with today's releases, not just sonically, but also artistically.

For some reason, Shostakovich's music turns the normally placid André Previn into an electrifying conductor, and these recordings of the Tenth and Thirteenth Symphonies are no exception. "Babi Yar" was recorded in 1979, and the Tenth Symphony was recorded in 1982 near the start of the digital era. Between the two, "Babi Yar" is marginally finer. Previn doesn't hold back, and the work's menacing nuances are brought right to the fore. The tension is maintained over the long, uninterrupted span of the last three movements even though Previn's tempos are on the slow side. Petkov has a beautiful voice and he uses it intelligently, and the men of the London Symphony Chorus are responsive to the texts' dramatic implications. Previn finds a similar vehemence for the Tenth, and if there are any reservations to be had, it's that he tends to reach his climaxes too soon. The third movement is arguably too fast, although the composer's indication of Allegretto does suggest a tempo that is faster than what we usually hear. In any event, this movement does lose some of its brutal weight when it is played this way. Still, it's an interesting alternate viewpoint. EMI loses some points by including neither texts nor translations for "Babi Yar"; otherwise, this twin-pack would have been an easy recommendation for the budget-minded newcomer to these works. I have no problem enthusiastically recommending it to anyone who desires provocative supplementary recordings, however.

Leonard Bernstein recorded both the Symphonie fantastique and Harold in Italy with the New York Philharmonic for Columbia (now Sony) before making these EMI recordings. The New York Symphonie fantastique is generally recommendable, but the Harold is too wayward and inconsistent for everyone but Bernstein fanatics. Well, it is a pleasure to report that everything came into place for Bernstein's 1976 remakes; in fact, the French Harold in Italy may be the finest on disc. Donald McInnes is both self-effacing and intense in the solo role, and he has tone for days. Bernstein is exciting without being vulgar (except, perhaps, for the very last bars, but at that point in this recording, one is willing to forgive him everything). For once, this seems like a grandly tragic work, not just some prettily picturesque concerto for viola and orchestra. The Symphonie fantastique is unwontedly suave, and here, Bernstein again finds more variety of color and shading than he did in his New York recording. The French orchestra may not have New York's group virtuosity, but they have the right timbre, and that counts for a lot in Berlioz. The engineering is top-drawer. Previn's overtures also are very fine. He plays them for excitement, although he doesn't always avoid that bandshell feeling - Previn clearly likes a good oom-pah. On the other hand, even Les Francs-Juges is exciting, and I can't remember another occasion when that's been true for me. The sound is a little dry. At this price, these recordings belong in anyone's Berlioz collection.

Yehudi Menuhin recorded all of Schubert's symponies, and here's hoping that this double fforte issue of the first six means that the remaining two are on their way, with some appropriate fillers. Menuhin's prodigious talents as a violinist tended to overshadow his considerable skills as a conductor - which only improved as time went on, it turns out. Although he conducted splendid recordings of music by Tchaikovsky, Elgar, and Tippett, to name just three, he was at his best in the Baroque and Classical repertoires. These Schubert recordings, taped between 1966 and 1968, are free of disfiguring quirks and idiosyncrasies. Perhaps there's little about them that's strikingly individual. Nevertheless, Menuhin's energy and high spirits make it easy to love these symphonies, so easily neglected (with the exception of the Fifth) in favor of the Eighth and Ninth. The "Menuhin Festival Orchestra" (was this a pick-up group?) is large enough to make these works' symphonic statures ring true, but not so large as to smother their charm. Everyone sounds alert, and the music shines with a sunny freshness. The Second Symphony is a highlight of this set. Menuhin eschews a purely athletic approach and allows the music to relax and smile. The harmonic tensions are there, but the conductor is more interested in balancing them with a very positive regard for sound itself. Menuhin's version of the Fifth Symphony does not have the lightness of Beecham's, but whose does? The sound has aged well, but the new annotations included with the set are indequate.

Certainly the recent film Hilary and Jackie has made even more people curious about cellist Jacqueline du Pré and her - to say the least - interesting life. She was only in her teens when she made the recordings contained on this new reissue, but it should be remembered that her career ended not long after; multiple sclerosis forced her to give up concertizing in 1973, and finally killed her in 1987. Generally, people either loved her for her emotional playing (which "spread" to her face and her entire body in what some found an alarming manner!) or criticized her for being a sort of musical tomboy. Even 12 years after her death, the polarization continues. In England, she can do no wrong; elsewhere, there is more room for objectivity. These BBC recordings are typical of her work, although there would be a bit more polish later on. The Bach suites are easy to enjoy. Her tone his sinewy and she dances her way through the Courantes and the Gigues with winning enthusiasm. Two movements of the Britten can only be described as tantalizing (no less for Stephen Kovacevich's pianism), and the de Falla suite features idiomatically throaty "singing" from the cellist. The Brahms sonata, live from the 1962 Edinburgh Festival, is idiosyncratic, and not without its instances of coarseness. Best of all, perhaps, are the Couperin (in which her teacher William Pleeth joins her) and the Handel, both of which induce her to temper her strength with mellowness.

Whenever I read Henry James, I get the feeling that he is pulling my leg. I get much the same impression whenever I hear Saint-Saëns's adorable piano concertos. Once the composer decides to roll up his sleeves and get serious, he is distracted by a nervous sylph in a ballet tutu, and the music rushes off in some other direction entirely. Saint-Saëns is the only composer who sits down to write a tribute to Bach and stands up having written the finale to Offenbach's latest operetta. Yes, this music is absolutely delicious - it's a sermon in rhinestones and a champagne Eucharist. The Second and Fourth Concertos are the most popular, although even these have been neglected as of late by our cynical world. The First Concerto hearkens back to Mendelssohn, whom Saint-Saëns greatly admired. Both the Third and the Fifth Concertos feature giddy finales, the latter with distinctly African overtones. (This concerto has been subtitled "The Egyptian.") In the "Wedding Cake" Caprice-Valse, the pianist sets sail on a whipped-cream sea of roulades and sparklingly fey filigree. The "Africa" Fantaisie is another souvenir of the composer's years in that continent. The local color is almost violently lurid; this would be a show-stopper at any "pops" concert, if only it were given a chance. But really, much the same could be said about any of these works. Collard spins out the froufrou with a perfectly straight face, which makes the jokes even funnier. He has the perfect light touch and agility for this music, and he realizes its requisite charm. Previn and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra partner him well, and the engineering is warm, brilliant, and detailed. These digital recordings were made between 1985 and 1987. The inclusion of "Wedding Cake and "Africa put this release, already a bargain, into a class of its own - look at those playing times!

Copyright © 1999, Raymond Tuttle