The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rózsa Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

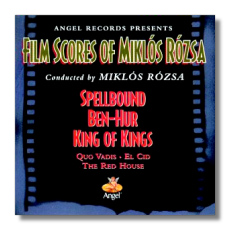

Miklós Rózsa

Film Scores

- Ben-Hur

- El Cid

- King of Kings

- The Red House (mono)

- Quo Vadis (mono)

- Spellbound (mono)

Uncredited orchestra/Miklós Rózsa

EMI 65993

Summary for the Busy Executive: Opulent.

Miklós Rózsa has emerged as one of the major Hollywood composers, an important figure who moved American film scoring from pseudo-Wagner and Tchaikovsky to a genuinely modern idiom. Since movie music gets little or no respect in most critical circles, very few people other than cranks like me think this a big deal. Honegger, a major pioneer in providing high-quality modern music for great movies, got Rózsa started. The young Hungarian composer had just enjoyed a major success with some concert works and had found out the sad truth that almost nobody makes a living writing classical music. He asked Honegger for advice on how to make ends meet, and Honegger hooked him up with the European movie business. Within a few months, Rózsa was scoring pictures for the Hungarian-British film mogul Alexander Korda. Korda brought Rózsa with him to Hollywood, and Rózsa immediately produced two classic scores: Thief of Bagdad and The Jungle Book. From then on, Rózsa wrote mainly for movies, with the occasional concert or chamber work thrown in. Almost everything he wrote exhibits exceptionally high workmanship and – no surprise – drama.

Most people probably know the music to the Biblical and pseudo-Biblical epics – Ben-Hur, Quo Vadis, and King of Kings – when Rózsa competed with fellow film composer Franz Waxman for the job of Kapellmeister to God. Yet, like every other film composer, Rózsa worked in a lot of different genres: fantasy, romance, costume drama, horror, psychological drama, and crime. In fact, I suspect the movies closest to his heart were probably the classic film noirs like Double Indemnity, The Lost Weekend, The Killers, The Red House, Brute Force, Naked City, and Asphalt Jungle, as well as the Mankiewicz Julius Caesar and the Minnelli Lust for Life. Yet it was almost never simply "a job of work" for Rózsa. Even clunkers like Diane, Young Bess, King of Kings, and Lydia evoked superb music from him. He seemed to know where the heart of the drama lay, even if the heart itself beat ever so faintly. Critics have sniffed at the gaudiness of his scoring, but the luxe almost always matches the subject and, even better, the image. He could also write extremely economically, as in the late score to the Resnais movie Providence (which sounds like the Palm Court band) and – one of my favorites – Crisis, entirely for solo guitar.

The extent to which movie music seeps into us without our conscious on the alert amazes me. Thirty years ago, a friend gave me a text to set, with the opening line "Quo vadis, Domine." I came up with a killer phrase that moreover fit the line and began to work. I showed my friend the sketches and was told that Rózsa had come up with the phrase first as the main theme of his score to the picture Quo Vadis. I knew I hadn't seen the movie recently, but dimly recalled that it played on TV when I was roughly eight. And the music stuck all those years. If nothing else, Rózsa's ideas impress and persist.

Rózsa bases his music on Hungarian folk song, without sounding like Bartók or Kodály: less astringent and more lyrical than Bartók, less impressionist than Kodály. As far as I'm concerned, his violin concerto ranks with the Bartók second – that is, one of the century's best. Film-music maven Christopher Palmer has pointed out the pentatonic basis of Hungarian folk melody common to the folk music of many other countries and other centuries. According to him, it provides Rózsa with a "golden key," a passport to many other times and places, invaluable to a film composer who got many different kinds of assignments. And yet is the music to Ben-Hur, for example, anything like music of Biblical times? No more than Korngold's music for The Adventures of Robin Hood is medieval English. Consequently, the idiom itself probably doesn't account for a great film composer's range, but the ability swiftly and convincingly to portray a scene or character does.

I find Hollywood epics – particularly the Biblical ones – garishly awful (the decadence and the piety seem so… protestant), but I watch 'em, just as I wolf down Big Macs and enjoy elaborate Vegas-style neon signs. I also think Charlton Heston a better actor than most people give him credit for. Essentially a classical stage actor, he had the misfortune to have to make an American career and the good luck that Hollywood happened on him. Most of his pictures out-and-out stink, including the ones for which people know him best, but he did manage to make several very good ones indeed – Dark City, The Private War of Major Benson, The Big Country, The War Lord, Will Penny, The Three Musketeers, The Four Musketeers – and two classics, Welles's Touch of Evil and Branagh's Hamlet. I recently caught Ben-Hur again on TV, having been unable to read the General Lew Wallace book without laughing, and was genuinely impressed with how much better the picture was. To some extent this was due to the script (on which Gore Vidal may or may not have worked), but the other two major helps were Heston and Rózsa (I've never been a fan of the director, William Wyler). Heston plays a man with his own agenda on the fringes of great events, and yet shaken and shaped by them. Rózsa's music gives the Poetic Dialogue and the De Mille-behemoth spectacle blood and spine.

As far as film-music recordings go, I prefer entire scores to separate cues. These are separate cues. Rózsa himself conducted more or less complete stereo recordings of at least four of the scores on this program: Ben-Hur (he recorded it twice; the second time on London/British Decca is the better), Quo Vadis, El Cid, and King of Kings. I don't believe any of them have appeared on CD. What you get from the complete scores is not only more glorious music, but an appreciation of how Rózsa built entire scores from just a few themes. Ben-Hur, for example, largely varies a small set representing Jesus, Ben-Hur, love, and Rome. You hear all of them in the "Prélude," as well as a tip of the hat to Honegger's Le Roi David in the "Parade of the Charioteers." One of Rózsa's best efforts, the score brought to the composer the third of his three Academy Awards. Just as the picture spawned a rash of more outtakes from the life of God, Rózsa's score essentially fixed a musical idiom for such pictures, as composers considered all the ways one could set the word "alleluia." My favorite sequence (and it seems to be mine alone), "Adoration of the Magi" – beautiful and appropriately rustic, with the orchestra interjecting the occasional moo – is once again missing from the excerpts. It's just this kind of thing that separates kitsch-meisters from a real artist. Don't be fooled by imitations.

The El Cid score doesn't quite reach the level of Ben-Hur. It's a bit repetitive and comparatively stiff, just like the movie itself. But the excerpts here dance with the vigor of Renaissance bransles, from which we get the word "brawl." The King of Kings music, undoubtedly the best thing in a truly crummy picture, refines the Ben-Hur idiom. It's one of Rózsa's most beautiful scores, but the critical panning – thoroughly deserved – of the film will probably prevent a "complete" recording of the music. I put quotes around "complete" mainly because nobody except scholars really wants an encyclopedic compendium of film cues, many of which make little sense without the images and dialogue they accompany. The film composer doesn't often get the opportunity for a sustained passage, beyond opening and closing credits. Instead, I mean the editing of the kind the late Christopher Palmer used to undertake (he worked for a time as Rózsa's assistant).

Quo Vadis was the picture that set Rózsa's biblical idiom. In my opinion, it's one of the best film scores to come out of Hollywood, or anywhere else for that matter. It's got grand, symphonic sweep. Again, it accompanies a ludicrous story and woebegone performances: Robert Taylor at his most wooden, Deborah Kerr almost always on the verge of tears for no good reason and annoyingly noble, and Peter Ustinov in the most flamboyant display of gibbering overacting since Charles Laughton as Henry VIII. For the London/Decca LP, Rózsa and Palmer fashioned from the scraps of cues a powerful score that made sense on its own and was moreover gorgeously recorded in Phase 4 stereo. The excerpts here (in monaural sound!) reflect palely on that glorious version. They give you almost no sense of the grand movement in the score or its climactic thrills. In other words, don't buy the CD for this. Perhaps enough people can pester London to release the Rózsa it has, including a similarly complete Ben-Hur, much preferable to the original soundtrack recording.

Some mistakenly credit the music to Hitchcock's psychological thriller Spellbound as the first use of the theremin in Hollywood, but Waxman had used it as early as The Bride of Frankenstein. Rózsa, however, may have been the first to take it out of the horror genre. The monster lurked no longer in the castle, but in ourselves. It became enormously popular, winning Rózsa his first Oscar and impelling the composer to create and record a "Spellbound" concerto (not really a concerto, but in show business billing counts for a lot), the Titanic soundtrack CD of its day. It's not one of Rózsa's strongest scores, any more than the movie ranks as one of Hitchcock's best, but its commercial success probably had something to do with breaking the hold of the Strauss-Tchaikovsky idiom in film music. Certainly directors like Hitchcock, Billy Wilder, Lewis Milestone, and John Huston became more aware of musical possibilities and were willing to go to bat for favorite and for new composers. During the 1940s, Rózsa scored mainly thrillers and modern dramas. The Red House – one of Edward G. Robinson's more absorbing movies – has escaped the notice of film revivalists and historians. In fact, I know it only through Rózsa's music, crisp, taut, and full of menace. "Screams in the Night" – one of the cues heard here – unusually combines high unison sopranos and theremin, which grants a disembodied, unearthly after-echo to the voices.

Rózsa's film music has been recorded, mostly in excerpts, quite often. I recommend his own recordings as at least capable, with the London/Decca Ben-Hur and Quo Vadis standing out. Elmer Bernstein recorded Madame Bovary, Young Bess, and Thief of Bagdad as relatively complete. None of these accounts is currently available on CD. Charles Gerhardt has a fabulous recording of bits on RCA 0911-2-RG (produced, incidentally, by George Korngold, the composer's son). The Gerhardt-Korngold collaboration for RCA was a fabulous one. If you come across one of their CDs, grab it.

For those to whom sound matters, the stereo cuts in transfer from analogue still hold up. The monaural tracks sound boxy, as I've said, to the detriment of Quo Vadis. The Spellbound tracks seem to be coming from a windup Victrola.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz