The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

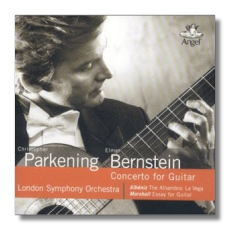

Christopher Parkening

Guitar Concerti

- Elmer Bernstein: Concerto for Guitar & Orchestra "For Two Christophers" *

- Isaac Albéniz: The Alhambra - "La Vega" (arr. J. Marshall)

- Jack Marshall: Essay for Guitar

Christopher Parkening, guitar

* London Symphony Orchestra/Elmer Bernstein

London Symphony Orchestra/Jack Marshall

EMI Angel 72435 56859 2 6 48:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: Great tone, busy fingers. Where's the music?.

Elmer Bernstein has a fairly solid reputation as one of the great Hollywood film composers, with scores that include To Kill a Mockingbird, Man with the Golden Arm, and The Magnificent Seven. He studied with Stefan Wolpe, among others, and many credit him as one of the principal figures who brought Hollywood film scoring into the Twentieth Century. He has also freely and generously helped young people break into the business. I'm especially fond of his Toccata for Toy Trains, a witty and inventive piece which perfectly accompanies a delightful documentary on model trains and stands on its own as a piece of music, besides.

Bernstein encouraged Christopher Parkening early in the guitarist's career. Parkening, in return, asked for a concerto. The virtuoso arranger and film-music scholar Christopher Palmer picked up on the request and kept noodging the composer, reluctant to begin due to his unfamiliarity with the guitar. By the time Bernstein completed the work, Christopher Parkening was middle-aged and Christopher Palmer had died. Bernstein dedicated his concerto to the "two Christophers."

Writing a movie score calls for different talents than writing a long symphonic work does, and Bernstein certainly knows the difference. Film music, outside of credits and main title sequences, typically runs in short spurts. The dramatic vividness of an idea takes precedence over the idea's ability to sustain extended development, as in a symphonic work. I hesitate to rate one method over another, since a film set to, say, a Bruckner symphony would be a very odd duck indeed (as well as a little short). Rózsa's symphony works in an entirely other way than his score for Ben-Hur. The skills are different and, in their proper contexts, appropriate. All that said, I can't call Bernstein's concerto a success, at least in the first two movements. The first movement lacks precisely the argumentative thrust and reach we expect from concert work. Furthermore, although the ideas in themselves hook onto the listener's attention, the rhetorical balance between guitar and orchestra is fundamentally askew. The guitar is, of course, a very quiet instrument. It doesn't take much from the orchestra to drown it out. Consequently, many composers fall into a trap of having the guitar comment on fuller statements of primary material in the orchestra, thus pushing the guitar into a secondary role. There are ways around this, one of which might be to reduce the orchestral forces, but Bernstein insists on a big sound - pretty much his Hollywood sound, as if he had fallen back on auto-pilot while orchestrating.

Troubles continue in the slow second movement, where, even with some heartfelt moments, the guitarist might as well not show up. Moreover, the main idea comes distressingly close to the song-theme of Rodrigo's classic Concierto de Aranjuez (think "rich Corinthian leather"), perhaps conflated with the slow movement of the Khachaturian piano concerto.

The rondo finale, however, succeeds like gangbusters. Bernstein uses the orchestra more economically and, just as important, allows the guitar to introduce the movement's main ideas. Come to think of it, that's Rodrigo's strategy as well. The orchestra comments on the guitar, rather than the other way around. There's also a wonderful moment when the guitar seems to leap out from among the agglomeration of players, to extend their material into new neighborhoods. The movement takes sprightly steps, just as Rodrigo's finale does, but this time Bernstein manages to say something of his own.

Jack Marshall - composer, conductor, and arranger, probably best known as the writer of The Munsters TV theme - happened to play the guitar himself. Unlike Bernstein, he knew the instrument. The CD takes two very early performances by Parkening from 1967 which showcase Marshall as arranger and composer. The arrangement of Albéniz's Alhambra plays with unusual guitar sonorities, but in a subtle way. Unfortunately, I don't care for the original piece but must admit that Marshall treats it lovingly and with taste. The difference between this arrangement and the Bernstein concerto is that the balance between the guitar and the ensemble - both in terms of decibels and of rhetorical importance - seems absolutely right throughout. One can say the same for the original Essay. Marshall scores lightly, the better to equalize guitar and the larger ensemble, and the ideas show an elegant composing taste. Compared to the Bernstein, however, as clunky as it sometimes becomes, Marshall's Essay seems "safe" and "contained," even though it does manage to charm.

Parkening seems in all these pieces a bit too laid back. He does best in the Albéniz - quite frankly, stunning guitar playing - but at no point does he rouse musical passions, even when the scores demand them. I don't play the guitar myself, and I defer to those who do. Most of them seem to enjoy Parkening in general. When I compare him with someone like Ricardo Cobo, however, I must admit that the regard for him puzzles me.

In all, a pretty disappointing disc.

Copyright © 2004, Steve Schwartz