The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Offenbach Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Jacques Offenbach

Orphée aux Enfers

Natalie Dessay

Laurent Naouri

Jean-Paul Fouchecourt

Yann Beuron

Choeur & Orchestre de l'Opera National de Lyon/Marc Minkowski

EMI Classics 56725 2CDs

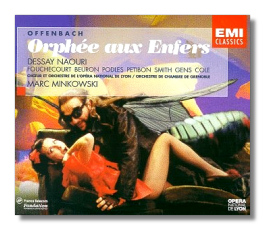

The CD cover says it all: a hirsute man dressed as a fly is seducing a comely leggy woman on a divan. Doesn't that make you want to listen to Jacques Offenbach's first successful operetta (1858 version)? The plot alone skewers classical themes. Orpheus and Eurydice quarrel constantly, mostly because she can't stand his fiddle playing. He is relieved when a snake bite spirits her off to the underworld, but Public Opinion forces him to pursue her. More absurd twists ensue, such as the rebellion of the gods on Mount Olympus, the rivalry of Jupiter and Pluto for Eurydice, the pursuit of Eurydice by a Lethe-addled John Styx, and two Bacchanales in the Underworld, both to the tune of the "infernal gallop," popularly known as the can-can.

The music itself is so delicious it is addictive. I don't know how many times I've played the ludicrous fly duet between Eurydice (Dessay) and Jupiter (Naouri). Hearing Dessay's coloratura voice buzzing like a fly is delightfully jarring. John Styx sings a tasty aria about once being king of Boeotia. Its never-changing rhythm and melismas parody eighteenth century love ballads. Dessay is splendid as the spoiled and willful Eurydice, always ready to strain her voice for comic effect. When Orpheus complains to the gods of his stolen Eurydice, he sings a tender quote from Gluck's "J'ai perdu mon Eurydice," which Diana, Cupid, and Venus promptly mock with croaky voices. The "Rondo-Saltarelle" of Mercury is lively and spirited, but the "Aux Armes, dieux et demi-dieux" chorus, in which the gods and demi-gods protest their ambrosia, reveals how well Offenbach could caricature the stirring military choruses of Verdian high opera. Most tasty is the "Rondeau des métamorphoses," in which the gods reproach Jupiter for his many indiscretions and rhythmically jeer him. This music rivals Rossini's in its sheer catchiness. The Choeur & Orchestre de l'Opera National de Lyon performs it superbly, never letting up on its frenetic pace. Even the recitatives – and there are many – breeze by, aided by snatches of indignation, accusation, and general over-the-top acting.

Although Orphée aux Enfers was performed more than 500 times, Offenbach was not satisfied with it. He wrote two other versions. In 1873, he transformed the opéra buffon into an opéra féerie (enchanted opera), nearly doubling its length. The next year he added a ballet. "It would wake the dead, this music," said Francisque Sarcey of the opulent, wild, and whirling dance numbers. As much as I would love to hear these later versions, I don't think a CD release of either is immanent. Perhaps the audience that relished their frenzied waltzes and infernal sarabandes is no longer with us, frozen in the extravagant burlesque of the Second Empire.

Copyright © 1999, Peter Bates