The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rachmaninoff Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

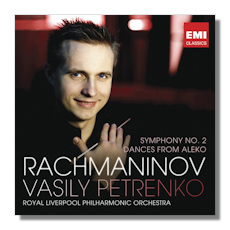

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Symphonies, Volume 2

- Dances from "Aleko"

- Symphony #2, Op. 27

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko

EMI 915473-2 73:05 DDD

For the second installment of their Rachmaninoff symphonies cycle for EMI, Vasily Petrenko and his Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra cover the most popular and significant of the corpus, the Second Symphony in E minor. If anything, this release is a ready reminder of how difficult this work is by its length, complex thematic material and emotional content. Yet today's major labels confidently invest in less than foremost ensembles to fulfill the task. And why wouldn't they? The hype is doing the rest. Reviewers already promoted the Liverpool forces to convincing interpreters of the Russian Romantic repertory. Sure they are. Bizarre then that by comparison the Rachmaninoff from old-school Russian maestros sounds like coming from a different solar system. With Petrenko/Liverpool there is very little of the dramatic grip and even less of the soulful lyricism and sometimes savage epic imagery that a Evgeny Svetlanov or a Kirill Kondrashin conjured with Rachmaninoff's symphonic work.

It depends of how you want your Rachmaninoff to sound, I suppose, and of course the streamlined elegance and the search for beauty of timbre are wholly admirable in Petrenko's reading. Yet, he also favors an approach which continually veers between a rather forced vitality and a much harder to sell reserve, without ever really deciding in which direction to go, to the point of undermining the symphony's sweep and expressivity in the process. This leads to some pretty exciting turbulent passages (the final Allegro vivace is a riot), but on the other hand there is little real substance to the formal beauty of much of the slower passages. Especially the opening Largo and the Andante sound by a lack of emphasis in the phrasing and insufficiently defined textural nuances in the string playing rather superficial and dull – the first movement's exposition repeat which Petrenko observes comes down as a dreaded moment in this case. The long Allegro moderato moves towards loud climaxes, although there is nothing much in the emotional climate that Petrenko creates to warrant these outbursts of sounds.

No matter how fine the strings, the basses are not present enough in the Andante and Rachmaninoff's polyphonic writing remains underexposed. And what are we to make of this timid clarinet solo in the Andante? In the end, as with Petrenko's previous release of the Third Symphony, there is little here that really grips, moves or gets under one's skin in the way that others have done with this tremendous music – the already mentioned Svetlanov, but also Mariss Jansons, Vladimir Ashkenazy, and Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, among others. It might reflect a contemporary approach to Rachmaninoff – uncut and favoring outsized contrasts, with some pretty hard kicks thrown in to make the point, but essentially cold and without hardly ever looking the score in the face.

Three delightful fragments from Rachmaninoff's early opera Aleko (1892) – The Women's Dance, Intermezzo and the Men's Dance – are offered as appetizer. Again, there is commendable attention to orchestral refinement, but Petrenko's phrasing is without much fantasy and his dances are far too polite to really convince. (By comparison, it's hard not to get up on your feet when Svetlanov performs the very same excerpts in this live performance from 1973.)

The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic surely plays with zest and alacrity. But regardless of the admirable progress the orchestra made under maestro Petrenko's guidance since September 2006, it still lacks the character and depth of the greatest formations. It may have something to do with the recording which in spite of a good dynamic range isn't very transparent and doesn't allow much detail in the sound picture, especially during tutti.

Copyright © 2013, Marc Haegeman