The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Silvestrov Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

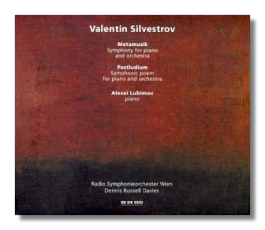

Valentin Silvestrov

- Metamusik

- Postludium

Alexei Lubimov, piano

Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Dennis Russell Davies

ECM New Series 1790 DDD 67:47

Valentin Silvestrov's fame rests largely on his Fifth Symphony, a work written in the early 1980s. The Fifth is typical of his music in that it seems to spend its 45-minute span coming unsprung: tense music early in the symphony is resolved in favor of a wrecked but picturesque landscape – or perhaps a nature morte in which everything is either prettily finished or coming to an end. The composer uses the gestures and textures of Romanticism, but not Romanticism's goal-directedness. The mood is elegiac, even morbid, and one feels that the music, like a dying shark in a deserted aquarium, can't go anywhere. This sense of always skipping ahead to the end, and of appropriating Romanticism's garments and putting legs through its armholes, has caused Silvestrov's music to be called "metamusic," in the sense of "beyond music." And sure enough, here's a "symphony for piano and orchestra," written in 1992, with that same title.

As Metamusik begins, we are plunged in the middle of a crisis: a glass is broken, if you will, and the shards achieve an, at best, uneasy resting place over the course of the next forty-five minutes. Often, the piano plays a decorative role, bubbling up from the depths as if to sing "Full fathom five." Less often, it gets the melody, but when it does, it presents it with an almost doodling simplicity. Flecks of color from the celesta intensify the impression of watery attenuation – dilution, if you will. As Metamusik plays through its endgame, it becomes more and more ethereally distant and regretful. Metamusik seems to be the point of contact between the music of Tōru Takemitsu and the last movement of the Ninth Symphony of Anton Bruckner.

Postludium (again, that theme of ending) was written in 1984. Although not specifically intended as such, it is a sort of prototype for Metamusik – a "symphonic poem for piano and orchestra." However, it is both shorter (just under twenty minutes) and thicker – that is to say, there are more layers of musical thought than in its successor. It also seems to be the more innocent of the two. Superficially, the two works are similar, but one of the nice things about recordings is that they allow you to keep repeating the experience until subtle differences begin to uncover themselves – and they will. With music of this high caliber, that goal is really worth the effort.

Lubimov was the dedicatee of Metamusik, and he already has recorded Postludium once before. (This new recording is preferable, largely because of the more subtle contribution from the orchestra.) He's clearly devoted much thought to this music and to its realization, and Dennis Russell Davies is, as always, a responsive and sensitive conductor.

The valuable booklet contains several essays about the music, including one written by the pianist. Clear but not clinical engineering suits these two works perfectly.

Copyright © 2003, Raymond Tuttle