The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Mussorgsky Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

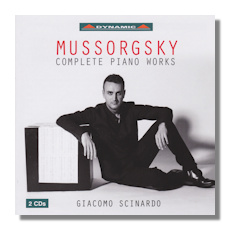

Modest Mussorgsky

The Complete Piano Works

- Pictures at an Exhibition

- A Tear

- The seamstress

- Méditation

- Scherzo in C Sharp minor

- Polkao "Porte-enseigne"

- Impromptu passioné

- Intermezzo in B minor "in modo classico"

- Ein Kinderscherz

- Souvenir d'enfance

- On the southern shore of the Crimea

- Near the southern shore of the Crimea

- Au village

- La capricieuse

- From Memories of Childhood

- Rêverie on a theme of V. A. Loginov

- Sorochintsy fair:

- Fair Scene

- Hopak

Giacomo Scinardo, piano

Dynamic DYN-CDS7786.02

To present all of Mussorgsky's piano works by one pianist in one place is a fine idea. This, original, piano version of "Pictures at an Exhibition" is the only one of all those works to be really well known – and even that is of course less well known than Ravel's orchestration. There's a freshness which comes through in the more spare original. To have "Pictures" and over a dozen pieces played sympathetically and sensitively by Italian Giacomo Scinardo (born in 1983), who studied with Phillip Entremont and Leslie Howard and has won many awards and competitions, would have been just as appealing. The repertoire is not so well known as it deserves to be – for Mussorgsky understood the piano and was an accomplished player early in his career… he was also writing for the instrument as early as 1852 (in his teens): the Polka for Piano "Porte-enseigne", Souvenir d'enfance, Scherzo for Piano in C sharp minor, Impromptu passioné and the Kinderscherz.

The corpus is varied, inspired, largely original, poetically rich and confident – somewhat in the way in which that of Mussorgsky's contemporary, Liszt was. Indeed, the latter was one of the first composers whose piano music Mussorgsky learned to play. Lovers of the latter will find depth and satisfaction even in the "salon" and impressionist/sketch pieces on these CDs. They may not remind us of Boris Godunov but they have the same strides of confidence, love of melody and gentle yet dispassionate inventiveness.

While amongst the better versions of the original, piano, version of "Pictures" are those by Steven Osborne (Hyperion 67896) or Alessio Bax (Signum 426), to have all the other works on one pair of CDs is useful. Giacomo Scinardo plays with style and insight. Perhaps he lacks a little the sense of the ideal dynamic range necessary to convey the richness with which Mussorgsky infused his solo piano writing: he neither attempted to paint the entire world, nor to scale it down unduly into two hands.

Scinardo's playing is decidedly romantic – listen to the tempo of, for instance, the "Cum mortuis" [CD.1 tr.14] in "Pictures". It's not in the least labored, nor over strung. He obviously feels the pull of the music, its gravity and depth. Yet Scinardo is able to keep the piece moving, to make us relish the way in which phrases and musical ideas build on one another. Such a calculated absence of linearity is not a very Russian style of interpreting the music, though; and may seem a little odd at first. There are times, too, when the kind of ferocity which one happily associates with an idiomatic performance of Ives (or even emphatic Beethoven) seems out of place – as though there were some extraneous point to be made by the player at all costs. But we never really discover what this point is. Nevertheless, to have the chance to discover what Mussorgsky can do in the medium (only Alice Ader on Fuga Libera 566 partially constitutes a comparable survey) is a delight. Scinardo is at his best in the tender, reflective works like Une Larme [CD.1 tr.17] and the Impromptu passioné [CD.2 tr.1], which is decidedly Chopinesque. Souvenir d'enfance [CD.2 tr.4] is played with particular sensitivity – and reminds one of Howard Skempton's dictum, "All music worth listening to, even when slow or contemplative, is marked, or coloured, by a sense of urgency"; this is slow and contemplative music, and the pianist ties it perfectly to Mussorgsky's sense of the subdued dramatic where shifting tonalities provide the tension, rather than declamatory bluster.

But unfortunately, the acoustic, the actual recording, lets this release down. For a few, it would be a mere oddity if the playing had been of great depth and accomplishment, or of major historical interest. For others the extra clanging and ringing sonority will, regrettably, be very intrusive. It's hard to know whether the venue for the recording (La Giara Musicale in the southern Sicilian town of Modica) was an inappropriate space, or if the microphones were poorly-placed and so picked up the undue "boom" which mars this recording. Or whether some technical fault crept in post-production. A sound, editing and mastering engineer is specifically credited on the CD insert and a tuner (of the Steinway Model D) and acoustic consultant in the accompanying booklet.

So it's a little strange that these major imperfections got past the Dynamic team, and seem to have escaped Scinardo. The result, sadly, is that the impression that you are listening in a church hall with minimal or absent dampening or an abandoned waiting room, swamps much of the nuance and finer details of music and playing. The lyricism which otherwise characterizes the piano world which Mussorgsky created also takes second place to the distractions of a ringing, and even rather amateurish non-specialist, recording from the middle of the last century. There are even places where what we used to dread as tape "wow" can be detected and notes waver. And whole passages – the opening of the B minor "Intermezzo" [CD.2 tr.2], for example – where much of the subtlety that should come from clarity and nuance is lost altogether as one notes rings into the next.

The booklet in Italian and English sets the scene, describing what makes Mussorgsky's piano writing so distinctive… it's definitely at the other end of the spectrum from the "Study" or the Conservertoire piece. Expansive, referencing worlds outside itself and as full of color as strict technique, these pieces mirror the operas. Scinardo is, frankly, a long way towards understanding this. But really can't be recommended because of the actual recording, or venue, or (re)mastering.

Copyright © 2018, Mark Sealey