The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Bainton Reviews

Boughton Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Edwardian Symphonists

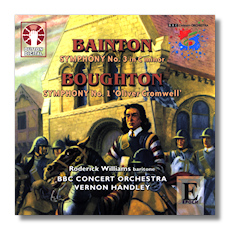

- Edgar Bainton: Symphony #3 in C minor

- Rutland Boughton: Symphony #1 "Oliver Cromwell" *

* Roderick Williams, baritone BBC Concert Orchestra/Vernon Handley Dutton CDLX7185 79:26

Summary for the Busy Executive: Good performances of interesting, if not knock-your-socks-off repertoire.

The number of Twentieth-Century British composers who keep coming up through the cracks astonishes me. You have, of course, the Mighty Five – Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Walton, Britten, and Tippett – and a very deep bench. You can't really call most of the also-rans the second string, based on quality alone. Not even Elgar wrote a choral work any better than Parry's Blest Pair of Sirens. Robert Simpson and Malcolm Arnold have nothing to apologize for as symphonists. And then you find treasures among the really obscure: Arnold Cooke, Franz Reizenstein, Matyas Seiber, Elizabeth Lutyens, John Hawkins, John Foulds, John Gardner, Richard Arnell, Cecil Armstrong Gibbs, Nicola LeFanu, and even Madeline Dring.

A pupil of Stanford, Edgar Bainton (1880-1956) began as a composing prodigy, becoming a professor of composition at twenty-one. I knew his choral music, written in an expert Edwardian style, much like the slightly older Edward Bairstow, with a keen sense of vocal color and the ability to write long musical paragraphs, not always easy to do in choral music. I had no idea he wrote instrumental music or music outside the church, but it doesn't really surprise me, since the choral music tends to move symphonically. The Third Symphony, begun in 1952, doesn't sound all that much different from Stanford. Where those like Holst and Vaughan Williams felt the need to get away from Stanford in order to find their own voices and in the process became two prominent shapers of British Modernism, Bainton pretty much accepted Stanford's post-Brahms idiom. A few dissonances that might have upset his teacher get through in this symphony, but the musical bones are pure Nineteenth Century.

Nevertheless, you would make a mistake dismissing Bainton as merely derivative. He has stuff of his own to say, but he can express himself in a received language. The third symphony sings with adult psychology and presents unusual architectural features as well.

The first movement begins with what sounds like the standard classical slow introduction followed by an allegro. As it proceeds, however, one realizes that these two things in reality comprise sort of a "first subject" group. Yet, the drama is what's really interesting. The slow part drags the music into a funk when it appears, while the quick part tries to rouse itself. About half-way through the movement, a serene pentatonic tune appears. Indeed, it emerges at various points throughout the entire symphony like a gold thread in a tapestry. Here, it serves as a fulcrum between the previous Sturm und Drang and a scherzo, which, by the way, incorporates the tune as part of its material. Thus, the composer splits the movement in half, and you wonder why. The scherzo comes across as more sardonic than jolly. Emotionally, it connects more to the first half of the movement than to the transition.

The second movement is a Brahmsian allegretto, but without the pastoral qualities of Brahms in that genre. It's uneasy in its tone, and the brief appearance of the pentatonic tune does little to dispel the gloom. Bainton had written the first two movements and had started the third when his wife died. Too depressed to go on, he laid the work aside for a long time. Eventually, friends and family kept badgering him to finish, and one friend actually announced in a journal that Bainton would have the symphony ready for performance. This got the composer going again.

The slow third movement, my favorite in the symphony, became a threnody to the composer's wife. Terrifically understated, the main theme shares certain musical topoi with the funeral march without necessarily becoming one, although it temporarily morphs in and out. Regret and private (not public) grief more than anything else, dominate the movement, as if the composer ruminated on the loss of a beautiful life. Bainton works so quietly here that any rise in dynamic becomes significant all out of proportion to its actual volume. About three minutes before the end, the pentatonic theme slips in, and the music radiantly transforms so that movement ends with great tenderness.

The fourth movement begins pentatonically, with affinities to Bax in the Twenties, and indeed seems to subject earlier ideas to a pentatonic template, as if to calm the emotional disturbances the composer has raised. It certainly solves the problem of what to do after the slow movement. It's no cheat. Bainton has found a musical metaphor for resolution, in the symphony's own terms, no small accomplishment.

Rutland Boughton (1878-1960), an altogether more flamboyant personality than Bainton, also studied with Stanford, but he mainly took Stanford's opera route. He established a festival at Glastonbury in the early part of the Twentieth Century, modeled after Bayreuth and based largely on Boughton's cycle of operas on the Arthurian legends, at a time when English opera was in a fairly parlous state. Indeed, one could argue that opera didn't become really viable in England until the Forties, after the war. Nevertheless, Boughton attracted significant support, including Elgar, Beecham, Holst, and Shaw, who wrote rave pieces praising the composer as the English Wagner. Ironically, the composer's greatest operatic success, Bethlehem (1915), caused the festival's collapse. Boughton put on a London production it in support of the General Strike of the Twenties, with Jesus born in a miner's shack and Herod as a plutocrat. It became a hit and so frightened away the necessary money to continue Glastonbury. The composer's reputation went into eclipse thereafter (his sympathies toward Communism didn't help), although he continued to compose in all genres. He continued to have his champions, notably Holst and Vaughan Williams. The latter remarked in 1949 that "In any other country, such a work as The Immortal Hour would have been in the repertoire years ago."

Fired by Shaw, I sought out The Immortal Hour, Bethlehem, and a bunch of chamber works. Only Bethlehem really stuck with me. Something rather old-fashioned about Boughton's sensibility – a bit like Granville Bantock and the minor writers of the Celtic Twilight – kept me away.

Inspired by Carlyle's Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches, Boughton's First Symphony (1905) shows the effects of post-Wagnerian thought on the symphony. Under Boughton, the symphony becomes a dramatic vehicle, though without a specific program, in five movements: a character study; Cromwell's letter to his wife, after the Battle of Dunbar; march of the Puritans; death scene. Boughton goes through the motions in the first movement of sonata-allegro, but it's really more of a series of riffs mainly on a "motto-theme" representing Cromwell himself. Boughton breaks up the theme and goes to town on the pieces. One thought suggests another and there is, as well, some padding, although not too much. Boughton's motto has such a distinctive shape that it can pull the music together when the composer needs to get back on track, and fortunately he knows when. Filled with lovely, individual chromatic harmonies, the slow second movement proceeds, again, more with dramatic than with musical logic. At times, it reminded me of a Korngold score for Warner Brothers. That is, I could imagine a scene it would accompany and can see Brenda Marshall on the screen. The Cromwell motto appears at least twice, variously transformed. For me, its best feature is its imaginative scoring, particularly toward the end, when violin and cello soloists duet against flutes and strings. As far as I care, Boughton could have left out the third movement, the Puritan march, altogether. He seems on automatic here. One gets nothing of the invention and depth of Elgar's "Pomp and Circumstance" marches, for example, from roughly the same period.

Nevertheless, what I think of as Boughton at his most authentic follows in the last movement, a setting of Cromwell's last prayer. In some ways, it suffers from late-Romantic notions of melody – what Vaughan Williams called "village curate improvising" – and it tends to sprawl. Boughton tries to inject structure into it with several fugato passages, but the counterpoint is a bit jejeune. Still, Boughton brings off wonderful passages for the baritone soloist, getting to the meat of Cromwell's words. However, the frame for the baritone strikes me as too conventional and not at all felt. Ironically, the "conventional gentleman" Bainton gives you something stronger than the rebel Boughton.

Both scores receive a strong reading from Vernon Handley. Roderick Williams sings poetically in the Boughton, with gorgeous, long phrases and with insight into the text. They make the best case for both composers. If I'm less enchanted with the Boughton, that may well be my fault.

Dutton has produced a wonderful series dedicated to neglected British music – Bowen, Bainton, Arnell, Alan Bush, Cyril Scott, and so on. I also enjoy the cover art, based on British transport posters. All in all, a project that shows a lot of care.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz.