The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Schumann Reviews

Vieru Reviews

Elgar Reviews

Boccherini Reviews

Haydn Reviews

Brahms Reviews

Locatelli Reviews

Saint-Saëns Reviews

Khachaturian Reviews

Shostakovich Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

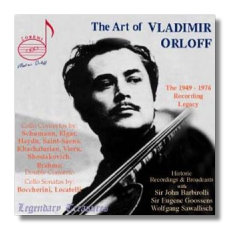

The Art of Vladimir Orloff

- Robert Schumann: Cello Concerto in A Major, Op. 129

- Anatol Vieru: Cello Concerto (1962) 2

- Edward Elgar: Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85

- Luigi Boccherini: Sonata #6 in A Major (arr. Piatti)

- Franz Joseph Haydn: Cello Concerto in C Major, Hob. VIIb/1

- Johannes Brahms: Concerto for Violin & Cello in A Major, Op. 102

- Pietro Locatelli: Sonata in D Major (arr. Piatti)

- Camille Saint-Saëns: Cello Concerto in A Major, Op. 33

- Aram Khatchaturian: Cello Concerto in E minor (1946)

- Dmitri Shostakovich: Cello Concerto #1, Op. 107

Vladimir Orloff, cello

Bucharest Symphony Orchestra/Mircea Cristescu (1962)

"George Enescu" Philharmonic Orchestra/Mircea Cristescu (1962)

Hallé Orchestra/John Barbirolli (9 August 1968)

Hallé Orchestra/Alfred Holocek (1952)

Vienna Tonkunstler Orchestra/Walter Weller (Feb. 1970)

Joseph Sivo, violin, Vienna Symphony Orchestra/Wolfgang Sawallisch (15 December 1968)

Vienna Symphony Orchestra/Marian Friedman (1976)

Bulgarian Radio Orchestra/Vassil Stefanov (1949)

"George Enescu" Philharmonic Orchestra/Eugene Goossens (1956)

l'Orchestre Philharmonique de l'O.R.T.F., Paris/Jean Perisson (5 May 1970)

Digital remastering and restoration by Jacob Harnoy

DOREMI DHR-7711/3 3CDs 3:54

It would seem to be simple common sense, in this age of recordings, to assume that the finest instrumentalists would also be widely known. Fame may not correlate exactly with talent, since matters of taste are involved, but after decades of listening and active collecting I expected to have heard, or at least heard of, all the important names in the field. Guess again.

How is it possible that such talent, and such beauty, can languish in obscurity? Here is an artist whose abilities place him in the first rank of performers of our century, but who is virtually unknown to American audiences despite a successful career as a soloist in Europe. Only a few of his recordings, which were mostly for Rumanian and Czech labels, were released in North America. Now at last we have a chance to hear Orloff. And what a pleasure it is.

It comes as no surprise to learn that Vladimir Orloff was born in Odessa; the region has given us much first-rate musical talent. Orloff won a number of major competitions in the late 1950s and was a member of the Vienna Philharmonic from 1964 to 1971. During his years in Europe he was very much in demand as a soloist and played with all the major orchestras. In 1970, he was invited to teach cello at the University of Toronto without an audition, on the strength of his reputation and the recommendation of János Starker. He spent the next twenty-five years mostly in Canada, teaching and playing with the Toronto Symphony and other Canadian orchestras. The fine Canadian cellist Ofra Harnoy was one of his students.

Orloff's playing conveys a great deal of authority and self-assurance without projecting a distinctive personality. His rhythmic sense is very precise and his tone is generally rich and full, particularly in the Romantic works. This style of playing makes me think of the stereotypical "old school" – warm and ingratiating. When compared with János Starker, who is very intense and driven, Orloff seems relaxed and friendly. Even Rostropovich, who falls somewhere in the middle of this range, has more of an edge to his playing.

The Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Khatchaturian, and Vieru concertos – and the two sonatas – enjoy good studio recordings that display Orloff's wide range of timbre and impressive technique. The other concertos in this set were not recorded under ideal conditions but were included as examples of Orloff's exceptional musicianship.

The Elgar has a muffled sound and distortion in the louder passages, but fortunately the soloist is prominent. This piece gives the impression of a slow reading. Another recording with the same conductor (Barbirolli) and Jacqueline du Pre as soloist is a few minutes longer than this but feels faster, perhaps because of the variety of accents used – there is more happening. This doesn't mean that I think du Pre gives a better performance, as the Elgar is a serious, even solemn piece that benefits from the more subdued interpretation that Orloff gives it.

Anatol Vieru, the least-known of the composers represented here, is a Rumanian who studied composition with Khatchaturian. His concerto is modern but apparently within the bounds set by Soviet policy, so there is no "excessive" dissonance. There is also nothing in the way of conventional thematic material. You won't find a tune, just gestures and fragments. Various novel effects and unusual timbres make this an interesting venture into spaces similar to those explored by Ligeti. This piece won first prize in a 1962 Geneva competition, and includes neo-Baroque and impressionist elements. It stands up well to repeated listening. This is the first and probably the only recording of the piece.

The Brahms Double Concerto is given a steady, serious reading by Sawallisch and the soloists. The sound quality of this broadcast is good, although some distortion and compression in the louder passages are inevitable from this source. Sivo and Orloff are natural partners, with fine unanimity and coordination. The finale is bright and energetic.

In the Haydn Concerto and the two Baroque sonatas we see another side of Orloff. Here his playing is full of glints of light, with a bright tone and crisp articulation that are so important in this style of music. His vibrato is controlled but used throughout to good effect. The orchestral and piano accompaniments are restrained and give the soloist the stage.

The last disc is even better than the first two. The Saint-Saëns Concerto sounds clear and well balanced even though it is the earliest recording on the set. A young Orloff plays it with energy and high spirits, fast and assertive.

Khatchaturian's long and complex Cello Concerto is given a highly persuasive reading. Orloff finds and conveys the complex emotions hidden under the cinematic veneer of Socialist Realism. I've always found Khatchaturian's high spirits appealing and his lyrical passages touching, but this performance brings out greater depth and range of feeling than expected, and the cellist must take most of the credit.

The final item in the set is a marvellous rendition of the Shostakovich First Concerto from 1959. Written when the composer was at the height of his powers, and premièred by Rostropovich, it is one of his most complex and persuasive works. Orloff's performance is full of subtlety and grace, ranging from vehemence to delicacy and even pathos. At every turn he is very much in sympathy with the demands of music, which are many and varied. The recording, from a Paris broadcast, is clear and shows almost no sign of the "enormous restoration" process described in the notes. In any condition this remarkable performance would be worth hearing.

A simple description of Orloff's style proves elusive. In part this is because he is a very shy man, not inclined to self-promotion. This would explain both his relative obscurity in America and the challenge in characterizing his playing. Orloff is one of those rare performers who are able to bring the ideas and feelings from the composer to the listener simply by getting out of the way. David Oistrakh – incidentally, a close friend of Orloff's – is another good example of this. Each artist has a very clean playing style, deep insight into the music, and no desire to assert his own personality. Of course, a great deal of technique is involved in these performances, but it is technique that does not draw attention to itself or to the performer. This is musicianship of the highest order.

Now that these examples of his artistry are once again generally available, Vladimir Orloff can take his place in the ranks of the great cellists in the era of recorded sound.

Copyright © 1998, Paul Geffen