The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Brahms Reviews

C. Schumann Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

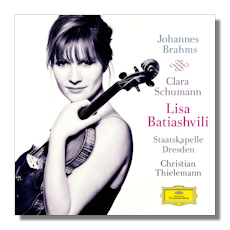

Johannes Brahms

Violin Concerto

- Johannes Brahms: Concerto for Violin in D Major, Op. 77

- Clara Schumann: 3 Romances for Violin & Piano, Op. 22

Lisa Batiashvili, violin

Alice Sara Ott, piano

Staatskapelle Dresden/Christian Thielemann

Deutsche Grammophon 4790086 DDD 48m

The Georgian violinist Lisa Batiashvili teams up for her second Deutsche Grammophon disc with the Staatskapelle Dresden and its principal conductor Christian Thielemann in this new recording of the Brahms Violin Concerto. The 33-year-old Batiashvili has quickly established herself as one of the most acclaimed and sought-after violinists of the day. She holds the position of "Capell-Virtuosin" in Dresden for the 2012/13 season, emphasizing her special relationship with the reputed orchestra and while falling short of being revelatory, her Brahms nonetheless makes a fine stand among the many reference recordings available.

What strikes immediately is the presence of the orchestra. Batiashvili's ravishingly sonorous and luminous violin (a 1715 Stradivarius that belonged to the dedicatee of the Concerto, Joseph Joachim) blends within the orchestral textures to a higher degree than one would expect in a concerto recording. The Staatskapelle Dresden is balanced forwardly and to some extent with a formation of this quality and character, this is a blessing. Thielemann secures a palette of tone and color from his orchestra that matches Batiashvili's. His vivid conducting and flexible tempi moreover create an epic canvas that suits her own passion. Interestingly, and justified by the overall approach, Batiashvili chose the lesser-known Ferruccio Busoni cadenza (1913), where her violin is accompanied by timpani and later even strings.

However, there is also a downside to this approach. In an interview Lisa Batiashvili reminded of the challenge facing the soloist when confronted with a big orchestra, yet at times in this recording it sounds as if she is bound to lose that confrontation, especially when the reverberant recording venue (the Lukaskirche in Dresden) magnifies and thickens the orchestral mass during tutti at the expense of the softer-grained violin – which the close miking of the solo instrument doesn't really compensate but instead produces an artificial sound. The most enchanting moments occur during the softer passages and the Adagio, where Batiashvili's violin in dialogue with the orchestra is heard to splendid effect. Thielemann weaves a ravishing polyphonic frame, while the lyricism of the central movement is rendered with tenderness (Batiashvili calls it an "impassioned declaration of love" of Brahms for Clara Schumann) as well as poise. Too bad then this transparency wasn't preserved in the last movement. Maestro Thielemann compared Brahms' music to one of these old steam locomotives that used to start out slowly but having gained speed there's nothing that could stop them. It's exactly that, but not all the passengers seem to have jumped on his train here.

An interesting, if somewhat slight extra consists of the three Romances for Violin and Piano, Op. 22 from Clara Schumann, which were also dedicated to Joachim. These are attractive pieces with plenty of character, sensitively played by Batiashvili joined by Alice Sara Ott on the piano. With just 48 minutes of playing time there was plenty of room for more.

Copyright © 2013, Marc Haegeman