The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Tchaikovsky Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

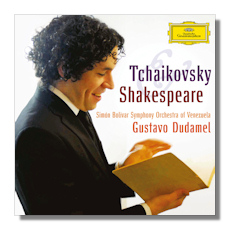

Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky

Shakespearian Fantasies

- Hamlet, Fantasy Overture after Shakespeare, Op. 67

- The Tempest, Symphonic Fantasy after Shakespeare, Op. 18

- Roméo and Juliet, Fantasy Overture after Shakespeare

Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela/Gustavo Dudamel

Deutsche Grammophon 4779355 DDD 65:35

With this trio of Shakespeare-inspired compositions Venezuelan boy wonder Gustavo Dudamel and the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra (the former "Youth" Orchestra has officially grown up) sign their second Tchaikovsky disc for Deutsche Grammophon. Unfortunately it is about as uneven and doubtful as the first (which paired "Francesca da Rimini" with Symphony #5). While the energy and enthusiasm at making music of this ensemble is certainly praiseworthy and may indeed serve as an example to many of the top orchestras, what is still missing here is an overall concept as much as a specific sound which could have pulled these pieces out of the unjustified category of mere sonic spectaculars. It's not that Dudamel lacks imagination, yet judging by this recording from February 2010 he is as yet unable to frame his ideas and present them into a convincing whole, while his phrasing and tempi changes tend to sound contrived rather than spontaneous.

Starting with the most frequently performed work, the "Roméo and Juliet" Fantasy Overture which comes last on the CD, Dudamel takes about as long as Leonard Bernstein's final version to make his point. However the main difference with Bernstein is that Dudamel lacks his theatricality and consideration, and merely plods where the older maestro is setting the stage for the drama to unleash. With Dudamel the opening section takes forever and while others used this inspired Tchaikovsky moment to create an almost unbearable sense of expectation as well as doom, here we get just proof that Dudamel loves to control his orchestra. When he lets the music speak for itself he secures passages of undeniable beauty (as in the opening bars of the famous love theme at 9:08 - no doubt this orchestra knows how to produce a delicate pianissimo sound) but when it comes to the real meaty stuff he falls short. By the slack handling of the transitions the fight sequences, emphasized by a prominent bass drum, leap out unwarrantedly spectacular, but nothing more. Moreover, Dudamel doesn't really dig in the love music, it all remains too episodic and the timid concluding moderato assai completes the overall feeling of disappointment.

"The Tempest" is one of Tchaikovsky's most underrated scores and deserves to be heard more often. Claudio Abbado has successfully championed the work for some time, while Russian chefs like Evgeny Svetlanov and Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov have left bitingly intense readings showing that "The Tempest" isn't the patchwork it is sometimes taken for. Dudamel's recording is scuttled by his somnolent tempi (for all its concentration the sublime opening evocation of the sea ripples on without any goal and sounds more Bruckner than Tchaikovsky) which the sudden attacks of energy, sometimes exposing the limitations of the string sections of the Simón Bolívar Symphony, cannot redeem. As in "Roméo and Juliet" there are occasional bright spots, but Dudamel's overreliance on control prevents the music from really taking flight.

The least disagreeable track is the "Hamlet" overture, although even here Dudamel cannot possibly rival the versions left by Evgeny Svetlanov, Riccardo Muti, Lorin Maazel, Leonard Bernstein or Leopold Stokowski, among others. Dudamel readily finds some of the darker tones of the work, but again a genuine feel for drama boasting the colorful characters and situations that should draw the listener in is largely absent. Ophelia lacks warmth and appears unattainable indeed, but at least here Dudamel manages a tight grip upon the work's structure.

This recording produced in Caracas balances the strings at the expense of brass and woodwinds. The sound is rather soft and could ideally be clearer, but there is an agreeable dynamic range. If we may believe the hype surrounding maestro Dudamel, this disc will attract his aficionados to Tchaikovsky. Whether they will have the reflex to continue with some great Tchaikovsky, remains however to be seen.

Copyright © 2011, Marc Haegeman