The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Higdon Reviews

Tchaikovsky Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

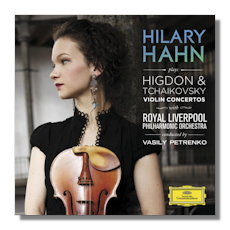

Higdon/Tchaikovsky

Concertos for Violin & Orchestra

- Jennifer Higdon: Violin Concerto

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35

Hilary Hahn, violin

Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko

Deutsche Grammophon 4778777 68:16

Summary for the Busy Executive: Terrific.

People don't always recognize a masterpiece immediately. It would have struck many of Tchaikovsky's contemporaries as improbable or at least bizarre that his violin concerto ever would have achieved its tremendous popularity. The first dedicatee, Leopold Auer, initially refused to play it, as did Iosif Kotek, the violinist who helped Tchaikovsky with the solo writing. The concerto finally premiered in Vienna under Richter and the soloist Adolph Brodsky to a mixed reception. The influential critic Eduard Hanslick thought it "long and pretentious" and in his review came up with one of the great brickbats of music criticism:

The violin is no longer played, but rent asunder, beaten black and blue. … Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto brings us face to face for the first time with the revolting idea: May there not also be musical compositions which we can hear stink?

Brahms told Tchaikovsky to his face that it was terrible. Tchaikovsky's reaction? "Brahms is a shit." Fortunately, Brodsky kept playing it, and eventually even Leopold Auer took it up (in his own heavily-edited version) and taught it to his students, some of the most illustrious violinists of the twentieth century. De rigeur, it belongs to just about every virtuoso's repertory. It's such a rouser of a piece – tuneful, colorful, exciting – I have a hard time seeing what put Hanslick's undies in a bunch.

On the other hand, Higdon's concerto, written especially for Hilary Hahn, has enjoyed tremendous success from the get-go. Hahn's popularity, even stardom, helped, but it certainly doesn't entirely account for the mountain of raves or for the award of the 2010 Pulitzer in music. Nevertheless, I've read some dissents, and who knows whether the piece will last? To me, it sounds pretty much like a classic, one of the great violin concerti of the new century, certainly worthy to take its place beside the John Adams. Then again, I have little interest in handicapping art. I either like a piece or don't, and I don't congratulate myself on my good taste, because what's the point? To me, art is pleasure.

Higdon approaches the concerto, particularly the role of soloist, in an unusual way. In the Tchaikovsky concerto, for example, the violinist gets to play the hero against the orchestral mass. In the Higdon, the soloist mainly comments as a member of smaller ensembles. Higdon also plays the solo violin against various sections: violin against percussion, against reeds, against the orchestral violins. The first movement, titled "1726" for some reason which Higdon won't reveal, begins as isolated pitches from the violin, accompanied by light percussion. The pitches coalesce into a phrase, the phrase grows into a melody, the solo line becomes a duet. The other instruments join in to create an impressive crescendo over a six-minute span. The texture evaporates, and we begin again the process of cohesion and fragmentation. Higdon calls the second movement, "Chaconni" (chaconnes). A chaconne is, of course, a harmonic sequence over which a melody is varied, as in the famous Bach chaconne for solo violin. Higdon uses several sequences – so more than one chaconne. The harmonies are so complicated, I can't follow them, except very roughly. However, it doesn't bother me. If anything, it's this movement that argues most strongly for Higdon's importance and the probable long life of this concerto. It sings in a way I've never heard before, and beautifully. We begin with one of the sequences, and eventually a thoughtful solo cello enters. Indeed, Higdon delays the violin's entry until two minutes in. The music goes into a long, long build to a powerful, but not necessarily loud climax, and then fades away, with the violin, which had been playing in its low and middle registers, finally untethered and soaring into the ether.

So far, the joys of this concerto have mostly been lyrical and meditative, reflecting Hahn's great strengths as a player. But concerti raise in us the expectation of at least a wow. Higdon reserves the sparks for the finale, "Flying Forward," a perpetuum mobile filled with jazzy syncopations, which dart through the listener's body. In her liner notes, Lynne S. Mazza writes that only with the final fortissimo chord does "the listener [realize] that it's time to take a breath."

I don't know how many hundreds of recordings of the Tchaikovsky you can choose from. Chances are your favorite violinist has a CD. I've always liked Erica Morini's account with Rodzinski conducting, as well has Heifetz/Reiner, Mutter/Karajan, Friedman/Ozawa, Francescatti/Schippers, Bell/Ashkenazy, Chen/Harding, and Elman/Boult. I may have forgotten three or four, but, then, I adore the Tchaikovsky concerto. The question arises that if you already have something you like, should you buy the Hahn? First, unlike most of the violinists above, Hahn does not use the Auer edition, full of cuts and reworkings, but the composer's original. Second, she takes an unusual view of the work. Most violinists treat the concerto as a showpiece, which it surely is, but that's about it. There's nothing wrong with this approach. As much as anyone, I like when technique and schmaltz overwhelm me. In fact, it never occurred to me that one could take such a detailed and musically thoughtful approach to the Tchaikovsky. Hahn, young as she is, has obviously worked on her interpretation over many years. It's not to everyone's taste. In fact, some reviewers have thought her technically tentative. I certainly don't hear that. Instead, I get an attention to the subtleties of Tchaikovsky's musical line, a willingness to linger on some moment. She certainly emphasizes the concerto's points of reflection more than you would expect, and instead of naïve gee-whiz, she makes you regard even the fireworks as high art. In short, this version is not about the violinist, but about Tchaikovsky.

I find Hahn wonderful in both. Petrenko and the Liverpudlians do well in the Tchaikovsky, accommodating themselves to Hahn's flexible line. The Higdon, as with almost every premiere recording of a contemporary work, has some ensemble problems, but not enough to skew a listener's appreciation. Some listeners have complained about the engineering. The orchestra "buries" the soloist. This, I think, due to listeners expecting the usual too-far-forward sonic image of the virtuoso, heroic soloist, absolutely wrong for the interaction between Hahn and the orchestra. The sonic ideal here lies closer to chamber music, especially in the Higdon. Some have also railed against "incompetent engineering" because (especially in the Higdon first movement) the soloist appears to jump from speaker to speaker. I suspect, however, that other single instruments "shadow" the soloist – in other words, an intentional effect of Higdon's scoring; a feature, not a bug. Although I've never claimed to have golden ears, the sound seems fine to me. The CD – for repertoire, performance, and sound – will probably find its way to one of my Bests of the Year.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.