The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Schoenberg Reviews

Sibelius Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

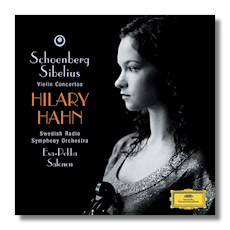

Hilary Hahn Plays 20th-Century Concertos

- Arnold Schoenberg: Concerto for Violin, Op. 36

- Jean Sibelius: Concerto for Violin, Op. 47

Hilary Hahn, violin

Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Esa-Pekka Salonen

Deutsche Grammophon 4777346 2008 62:54

If you go to ArkivMusic.com for this recording and read the recommendation by David Hurwitz written for ClassicsToday.com, you can read that Schoenberg's "Violin Concerto is notorious for standing among the ugliest pieces of music ever conceived by the human mind…" This comment sent me to Slonimsky's Lexicon of Musical Invective, which preserves some of the 1940 Philadelphia Record review of the work's première, written by Edwin H. Schloss, who called it "the most cacophonous world première ever heard here…" along with the kind of specific analogies that fill the Lexicon, including some aspersions on the Chinese language.

Although there are some pieces of music I have found repellent, this is not one of them and it has never occurred to me to call any piece of music ugly, though I suppose I could come up with one if I tried. The beautiful way Hahn plays this piece would take it out of contention for me in such an exercise. I would not be inclined to say that the work is "beautiful" throughout. (Some of it is.) Its composer probably would not have been inclined to say that either. In saying that "there's a lot of brilliant and (yes) expressive invention going on" in it, Hurwitz comes much closer to the nature of this important work.

Well before the First World War Schoenberg "adopted the tenets of Expressionism," as Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians puts it. For Expressionism, in the words of George L. Mosse's The Culture of Western Europe, "the usual forms of beauty and ugliness were irrelevant; what mattered was the spontaneity of expression." Although Schoenberg's composed his twelve-tone Violin Concerto well past the usual period into which the Expressionist movement is placed, I am not sure that Schoenberg ever entirely abandoned the spirit of Expressionism.

The expressiveness in this work ranges from the pleasant to the harsh, from bracing to edgy. The music flows, if typically in short phrases, and strong dissonance is only occasional. Hahn finds in the work "grace, wit, lyricism, romanticism and drama" having "an impact that is almost visual – not surprising for a composer who was also a painter." In an interview (at Violinist.com) Hahn responds to a question from Laurie Niles," Is it a piece that's built on tone rows?" with "I don't care. I really don't look at things from that perspective. It doesn't matter how a melody is constructed, it's still a melody." And she would have delighted Schoenberg with her conviction that children at least could learn to hum tone rows.

In this performance Hahn's tone is full, her phrasing assured. The soloist and the orchestra play well together, and the recording is excellent. If you are among the many resistant to atonal music but are willing to give this a try, you might begin with the slow movement, the Andante grazioso. (Hurwitz suggests the finale.) Oh, yes, for all Schoenberg's formal innovations, this work is in the traditional three movements, fast, slow and fast.

It is universally agreed that the Schoenberg Violin Concerto is extremely difficult to play. Heifetz gave it up as impossible, saying he would need a six- fingered hand. Hahn says that she "had to train my hands to adopt positions completely new to me," and that it took her two years to be able to play the work comfortably up to "the oft-ignored tempi printed in the score." This from the Hahn who told me after her recent Milwaukee appearance that she expected to learn the not-yet-finished Higdon concerto "in the usual time" and that learning the notes generally represents the easy part of developing a performance. For orchestras to learn this work, Hahn says, it requires six hours of rehearsal. Once mastered, this work proved, in the 21st century, to be "a hit. Orchestras and conductors brought the music to life. Audiences jumped to their feet," she reports.

Given my own tastes, I doubt that the Schoenberg will ever be among my favorite violin concertos. The Sibelius I have loved all my life, though, and if I were forced to select one concerto for a Siberian exile, it might well be this one. Hahn says that it took her years to make sense of it, formally, but that was never the slightest concern of mine. I find it both gorgeous and exciting and have never tired of it. The version of it that I bonded with was David Oistrakh's with Sixten Ehrling and the Stockholm Festival Orchestra on an early Angel mono record, and I still admire this performance. There is a nice little bounce at one point that I haven't heard in any other performance and Oistrakh did not mind leaning into his strings to produce an expressive yawp at points. Perhaps the closest I have heard to the intensity of this old recording, especially in the first movement, was Cho-Liang Lin with exactly the partners Hahn has twenty years later: Salonen and the Swedish Radio Symphony – recorded in the same hall. This is not to suggest that Hahn does not also have plenty of intensity, but her aim was to emphasize lyricism. Other recordings I know include one with Zino Francescati with Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, by far the fastest (in all movements) I've heard; I don't care for it. Another is with Leonidas Kavakos with Vänskä and the Lahti Symphony; they have by far the slowest Adagio. Hahn's is one of the best and its sound is exemplary.

I recommend this recording.

Copyright © 2008, R. James Tobin