The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Berio Reviews

Golijov Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Luciano Berio / Osvaldo Golijov

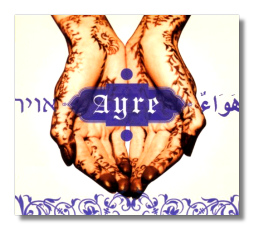

- Osvaldo Golijov: Ayre

- Luciano Berio: Folk Songs

Dawn Upshaw, soprano

The Andalucian Dogs

Deutsche Grammophon 477541-4 DDD 62:02

Summary for the Busy Executive: A modern classic and one that might be.

Luciano Berio, I suspect, looms in most music-lovers' minds a bit like the cartoonist Koren's shaggy monsters. One doesn't look forward to spending time listening to him. I admit I don't care for some of his work, but in general, he strikes me as an extremely lyrical composer, nowhere more so than in his Folk Songs (1964). It was, of course, the era of the folk song, particularly of the "urban" folk movement, the heirs of Seeger and Guthrie, like just about anybody on the old Elektra label plus Joan Baez. Berio tuned in, but not quite so Anglo-centrically. For him, a transplanted Italian, folk music roamed a bit more widely. He set tunes not only from his native Italy, as well as Sicily and Sardinia, but from France, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and the United States. He composed the piece for his then-wife, the super-mezzo Cathy Berberian (hence the Armenian and Azerbaijan songs), one of the great singers of the century.

Folk Songs starts out in the Appalachians, with not exactly folk music, but two classic tunes by John Jacob Niles: "Black is the color of my true love's hair" and "I wonder as I wander." We open with a gorgeous viola solo evoking the mountain fiddle, and the voice coming in and proceeding senza misura, ad lib if you prefer, almost disembodied, the singer singing to herself. They pull together with "I wonder" as the harp joins in. Throughout the entire work, Berio draws an extraordinary variety of sounds, from winsome to lush, from the instrumental ensemble – flute, viola, harp, clarinet, cello, and percussion. The small group proves versatile and capable of, on occasion, a very full sound indeed. Oddly enough, the Italian songs sound more Spanish than anything else, and Berio's arrangements remind me of Falla, around the time of El Amor Brujo. The composer also sets one of Canteloube's selections from Chants d' Auvergne – the one that says essentially, "Wives! Ya can't live with 'em, ya can't live without 'em." For me, this counts as one of the most beautiful vocal works of the Twentieth Century. If you don't know it, you should.

Argentinian Osvaldo Golijov, of Eastern European Jewish family, doesn't have to travel around as much as Berio to get variety. He's practically a United Nations all by himself. In Ayre, he pretty much confines himself to the Iberian peninsula during the Spanish Golden Age. The title itself calls to mind the great era of Elizabethan lute song. Golijov sets Sephardic texts, Arab Christian texts, Spanish Christian texts, and, memorably, a gorgeous, Lorca-like poem by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Almost every song speaks of either violence, loss, or displacement. To a tune that sounds like a lullaby, for example, a woman eats the body of her son. If there's a specific message underlying any of this – and it wouldn't surprise me – I have little idea what it could be. Right now, the piece comes across as a gigantic vague hint. The instrumental ensemble, slightly larger than Berio's, seems somehow a bit more constricted, but it includes digital electronics and an amplified accordion. The sound it makes draws largely on what I'd call Mediterranean Pop, perhaps because of the accordion. Two of the numbers were actually composed by long-time Golijov collaborator, the guitarist Gustavo Santaoballa, who also produced the recording.

The piece starts out full of beans. For the first four numbers, Golijov convinces you that you are hearing a masterpiece. Then the vim seems to leave and return fitfully (excepting the Darwish setting), although Golijov recovers by the end. Right now, after several hearings, I don't know whether the piece will grow on me or another, stronger performance (although I find it difficult to imagine a better one) will blow away my reservations.

I admire Dawn Upshaw tremendously for her interest in contemporary music. It's yielded some wonderful albums. She doesn't have the greatest voice in the world, but she's intelligent as hell and communicates like gangbusters. Unfortunately, in the Berio, she competes with one of the finest singers of modern times, Cathy Berberian, who quite simply owned the work. Berberian recorded it for RCA in the late Sixties (I bought the LP) with Berio conducting (RCA transferred the performance to CD). She brings so many shades of meaning to these songs, that she obscures the straightforward Upshaw. Upshaw operates at Berberian's level in the Golijov, but not in the Berio. The ensemble and the recording are first-class.

Copyright © 2008, Steve Schwartz